When you’ve established yourself the way the National Ballet of Canada has, it could become easy to rest on your laurels and congratulate yourself on a job well done. In that respect, much credit goes to the company for going out on a limb with The Man in Black, Chroma, Allegro Brillante and Carousel (A Dance). Ballet is an art that relies heavily on tradition, so it’s refreshing to see it evolve without losing sight of its roots.

The four short works each contributed something different to the overall picture: colour, lack of colour, emotion and dazzling artistry. Assembling the pieces this way was an interesting choice, as each ballet was strong enough to stand on its own, yet concise enough to be one-quarter of a larger and more ambitious project.

The program didn’t start off terribly strongly, with Allegro Brillante not as tight, smooth or fine-lined as it had the potential to be. The music was Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concert No. 3 that, despite being an unfinished symphony converted into one work, had the composer’s touch all over it, with notes that seamlessly flow into one another, deceptive in their transition and movement.

And yet, the dancers didn’t always reflect this, with the opening-night cast of Xiao Nan Yu and McGee Maddox looking, at times, as though they had to consciously think about their next steps. While Xiao and Maddox were technically good, they were never great; most interesting was the corps, although they seemed scattered in their footwork and the line of their arms seemed loose. There was an unevenness to the overall aesthetic that detracted from its potential beauty, and one would expect the lead dancers to set a stronger example.

But the sixteen minutes of Allegro Brillante proved to be a distant memory once conductor David Briskin led the orchestra into the Rodgers and Hammerstein-scored Carousel (A Dance) inspired by the 1945 musical. The sweetly romantic music was perfectly in sync with the dancing, with the corps, dressed in Grease-style garb à la the final carnival scene in the movie, positioned to form a carousel.

Jillian Vanstone and Harrison James (opening-night lead performers) had excellent chemistry together, taking their pas de deux to a new level. As Vanstone stood on pointe and James lifted her in the air, they seemed to fall in love before our eyes, under the simple but effective string of Christmas lights. As their movements alternated between languid and sharp, Christopher Wheeldon’s choreography had everyone in the audience spellbound, which is no easy feat in this tech-immersed age. It’s an interesting juxtaposition of restraint and unbridled emotion, with the U.K.-born Wheeldon using the primal nature of the waltz — the lub-dub of the beating heart — in conjunction with the carefree romance of a late-night carousel ride. Carousel has shades of An American in Paris, a movie that inspired Wheeldon to start dancing and one he transformed into a ballet.

The magic knitt by Carousel (A Dance) soon gave way to the sombre melancholia of The Man in Black set to the music of Johnny Cash, whose covers of John Lennon and Paul McCartney, Ian Tyson, John R. Cash, Gordon Lightfoot, Trent Reznor and Bruce Springsteen provided the score.

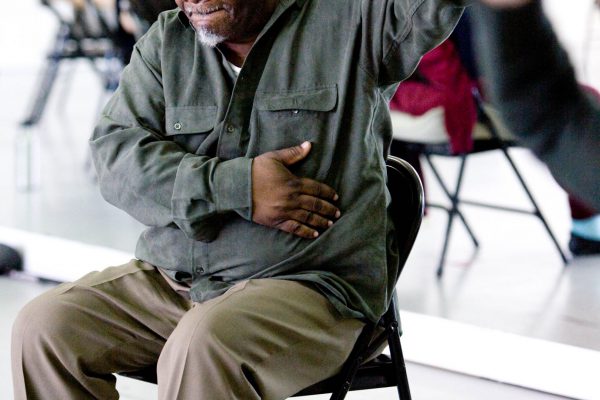

But this ballet departed sharply from the first two in terms of style. Gone were the corps and any hint of emotional lightness and, in their place, were four dancers (James Leja, Rebekah Rimsay, Piotr Stanczyk, Robert Stephen on opening night) dressed in varying styles of black.

If there’s one thing almost all of Johnny Cash’s music creates, it’s a feeling of impenetrable sadness, whether through the gravelly baritone of his voice or through the woebegone lyrics he’s singing. And there are few better minds at the National Ballet capable of wrenching out every possible emotion than choreographer and former NBoC artistic director James Kudelka. He’s directed his dancers into a constantly moving mass of grief and sorrow that occasionally splinters but comes back together in the end. There’s also an inherent risk of choreographing movements that follow the lyrics too closely, but Kudelka applies a poetic, abstract touch that keeps it on this side of beautiful.

The dancing can be roughly defined as country, but Kudelka’s twisted it with ballet forms so the end product resembles something almost grotesquely beautiful, much like Cash’s voice at the end of his life. It wasn’t always classically pretty but it was something you couldn’t ignore.

Finishing things off was Chroma, which was so dramatically different from the previous three, it could have easily stood on its own. The stage (created by British minimalist architect John Pawson) was designed to be stripped of colour and entirely white, with a cutout rectangle at the back that acted as both an anchor and point of transition for the dancers.

The dancers themselves wore pale, skin-coloured suits and neutral expressions and with their lithe movements, they presented a strong sense of androgyny. They squeezed their bodies into impossibly tight shapes, with the females (Greta Hodgkinson, Xiao Nan Yu, Tanya Howard and Svetlana Lunkina on opening night) able to bend backward almost in half.

With music provided by The White Stripes — Joby Talbot and Jack White — and choreography by British choreographer Wayne McGregor (whose trademark of art-meets-visual-technology combines with his theatrical experience to deliberately strip away the dancers’ personalities), Chroma seemed like an unlikely pairing of music, movement and aesthetic. But as the music reached a feverish crescendo in each song and the dancers moved faster and faster, it quickly morphed into something you couldn’t take your eyes off. And of all the pieces, Chroma showed just how much athleticism the human body is capable of. It was a treat for the eyes on so many levels but, if nothing else, it was astounding to see what these dancers are physically capable of doing.

There’s a point in Chroma where the stage suddenly erupts in a blinding white light and it’s an apt way of looking at the evening as a whole. Just when you get lulled into one movement or piece, the next arrives in such a radically different form that you need to blink a few times to adjust but after a couple of seconds, you’re immersed in a new mood.

Tagged: Ballet, Choreography, Contemporary, Emerging Arts Critics Programme, Performance, ON , Toronto