A student-choreographed routine included dancers wearing slave and master outfits and an attempted tribal dance in dashikis and coloured “Afro” wigs to disco movements. This was April 2018, and the performance held in Barrie, Ontario, sparked a controversial social media reaction on cultural ethics. All the indicators — time periods, music, clothing references, representation of Black hair styles — add to a multi-layered conversation about stereotypes, race and culture in dance. This performance at SPARK Dance Competition by Eastview Secondary School students led to disbelief from some of the audience members. Bear Creek Secondary School student Rhiannon Hoover took to Twitter to express how disturbed she was by the cultural misrepresentation and cultural appropriation:

“I’m sorry what? What gives you the right to appropriate Black Culture through pretending to be slaves, wearing an embroidered robe that looks ‘African’ to you, and wearing clown wigs? This is disgusting.”

Titled Black Dance Evolution, the performance raised poignant questions: Who gets to tell the story of cultural trauma? Whose bodies tell the stories of Black or African diasporic experiences? Hoover believes artists who are from the culture should be given the platform to lead and share their stories or trauma. She goes further to reiterate that anyone can be involved in sharing the story but that the cast should predominately be representative of Black artists, and she writes, “The best way to understand Black experience is by listening to members of that community and finding ways to uplift their voices.”

Reaction to Hoover’s tweet, which included a video clip of the dance, reopened debate and a level of critical consciousness in the presentation of ethnocultural movement and expressions, especially when it is culturally sensitive material. The Barrie performance speaks of rampant privilege to decide, engage and present cultural art forms with no interrogation of one’s positionality to the experiences and realities of another ethnic culture. As creatives, we live in a social time and digital age when cultures are voicing that individuals cannot be ill-informed, erase historical cultural knowledge and feel entitled to speak on another’s narrative. Did the African-Canadian or diasporic community know of this performance or were they consulted? Were dance artists from African, Caribbean or African-Canadian backgrounds brought in to work with the students? Black communities want to tell their own stories of Black experience. Another community cannot represent those authentic stories without offence or being checked on one’s privilege by said community, the lack of which would be a gross misunderstanding of allyship in the arts and the needs of a community. An ally cannot speak of my reality and experience or decide my will.

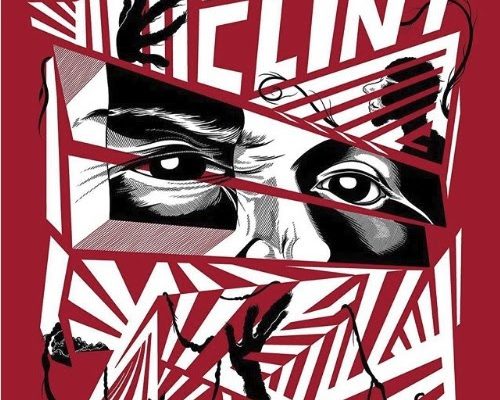

Simultaneously, in this age of celebration for Canada’s 150th year since Confederation, another dance production is an example of a thought-provoking story of cultural trauma that is seldom told. Cry Freedom made its world premiere May 11 through 13, as part of Harbourfront’s Next Steps 2018 series. This bold, multidisciplinary work is Ballet Creole’s commemoration of the 225th anniversary of a story of an enslaved woman in Upper Canada (early Ontario), whose courageous actions in 1793 were a catalyst to pass legislation in British colonies to restrict the slave trade. Chloe Cooley was violently tied and sold in the Niagara River area and trafficked into New York state where slavery was still legal. Her violent screams of resistance spoke of protest and the ignored voices and rights of many Black women and enslaved Africans in Ontario and Canada.

Cry Freedom required emotionally invoked research due to the sensitive context and knowledgeable musicians, choreographic team and cast. This was key to demonstrate the featured ethnic groups before and during enslavement and after emancipation, while also drawing from African influences. In addition, collaborators included allies, including the Ontario Black History Society and the Canadian Caribbean Association of Halton, and respected playwrights of colour who are versed in global contexts. The authentic music required a descendant from a djeli or griot — an oral historian who preserves the lineage and transmits his people’s history. Artistic Director Patrick Parson commissioned the artistry of Amadou Kienou, a djembefola (master percussionist who plays a djembe drum) and descendant from a family of griots of the Dafin people.

The dancers are descendants of African, Latin American and Caribbean cultures who illustrated a chronological time of uncolonized African dance bodies and how it navigated captivity and plantation life towards slave abolition. The opening procession, from the patron’s seating to the stage performance, included joyful dancers and live musicians from Creole Drummatix as well as Burkina Faso’s master drummer Kienou. The performers invited the audience to move and engage within their seats, just as ancestors include call-and-response and community interactions in a pre-colonial West African context. As a practitioner of the represented genres, I recognized the dance and rhythm vocabulary using indigenous instruments from the featured ethnic communities. A broad dance vocabulary and use of the stage, along with song and live rhythm, called attention to the fusion of contemporary and modern movements with traditional djembe dance styles.

To depict the cultural trauma of Cooley, the audience was brought to a time and place when African slaves were held in bondage and sold as chattel. Through multimedia imagery including song theatre, orality and a live drumming ensemble, the dancers, actors and musicians portrayed a slave narrative of pain that included a choreographed scene of captivity on the slave ship and a slave auction. In the background, vivid onscreen images of the dehumanizing transatlantic slave trade, along with monologues, spoken word, chants and passionately fuelled movement, confronted the audience’s position of privilege towards historical oppression. The dancers’ bodies told an unwavering story with an array of emotions by documenting Cooley’s consciousness in a way that was respectful, responsible and culturally representative.

As a cultural dance practitioner and educator from the African and Caribbean diaspora, I am called to understand that there are growing conversations to acknowledge the original inhabitants and the land that we occupy. As a settler, I understand that cultural pluralism gives artists space to explore, learn and participate in diverse forms of movement, while not contributing to the too-present erasure of treaty peoples and their culture(s). In the wake of the Barrie performance, a statement from the Simcoe County District School Board defended its students by stating that there was no ill-intent to be disrespectful and recognized the need for those involved to have continuous learning and coaching in equity, diversity and inclusion principles. There is more dialogue that could and should take place between cultural artists and Simcoe County District School Board in the future.

When movement and choreography represent an ethnic group’s culture, do we consider the ethical ramifications? Where are the considerations for which stories are told and how these stories are told? Although the Eastview Secondary dance students were provided topics of oppression in their semester’s curriculum, that does not mean authority was given by a diasporic community to demonstrate or represent their history. As artists, we are becoming more immersed in cultural appropriation versus appreciation dialogue, and there is a need to integrate earlier conversations on oppression and cultural appropriation with children and youth, in this instance. Therefore, equity and inclusion in action is hiring diverse artists of colour to work and perform in schools. This is the type of dance education I am involved in with schools, artistic projects and research, using a culturally responsive lens. I boldly cry and scream, on behalf of myself and other cultural dance educators, to reiterate our existence, and we are not invisible to approach for arts engagement.

A strategic priority would be including cultural arts practitioners to educate and engage with monocultural school communities to raise intercultural awareness. Ideally, Eastview Secondary would have benefited by bearing witness to Ballet Creole’s cultural story. The audience echoed this need and called on Parsons to tour this work to educate our uniformed African-Canadian children during the talkback. Ironically, this is the first year that school boards did not respond to Ballet Creole’s invitation to attend a matinee, which would have showcased Cry Freedom. Although social justice and equity are to be included in boards, there are still institutional “chains” to break through, using the arts, to reach the multicultural audiences we engage with. This movement and musical exploration took the shackles off our minds with an untold slavery in Canada, referenced by a diasporic community who owns the story, who were historically impacted and negotiate through funding structures to cry that artistic freedom. By using physicality, polyrhythm and fluid body movements to translate joy, tragedy, pain, resistance and silence, Cry Freedom eloquently disrupts the dominant narrative to honour the tears of its ancestors.

~

A little goes a long way. Donate to The Dance Current today to support bold and inclusive coverage of dance in Canada.

Tagged: Contemporary, Cultural Commentary, West African, Writers & Readers, ON , Toronto