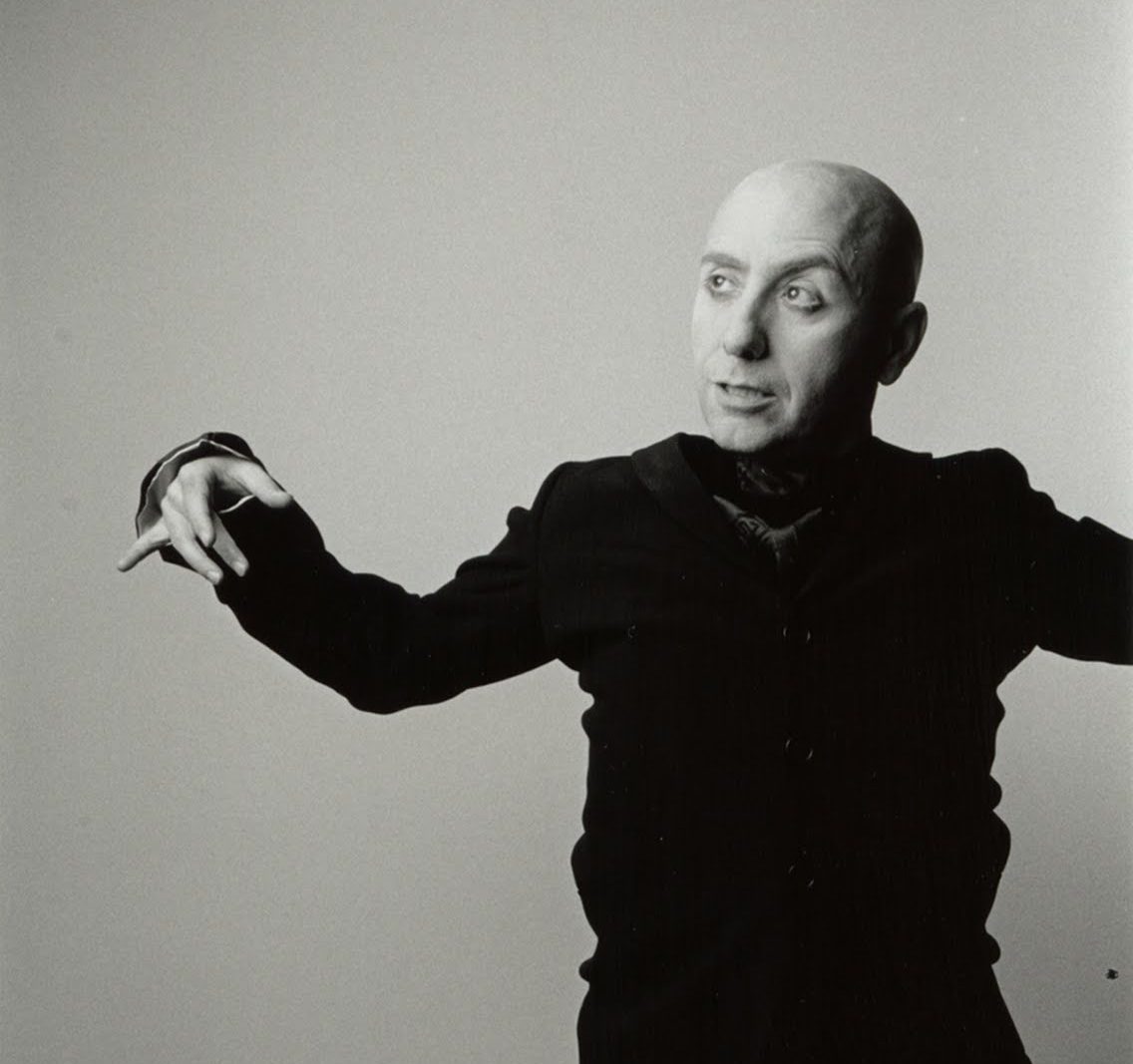

Tedd Robinson took up residence in the Pontiac, Québec, in 2005 and has been presenting dance in his barn since the summer of 2007. Robinson first rose to prominence as artistic director of Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dancers. He moved to Ottawa in 1990 and is now firmly established as a choreographer, solo artist and educator. Robinson is artistic director of 10 Gates Dancing Inc., a non-profit company formed in 1998. His work is influenced by his six years of study as a monk in the Hakukaze soto zen monastery, Ottawa. Robinson is a National Arts Centre Associate Dance Artist.

“My training was based in Euro-centric American-influenced modern dance but my choreographic style has developed during its nearly thirty-year journey to be something close to self-expression, something that I have labelled in the past as ‘abstract theatrical narrative’. I think I would term it now ‘abstract theatrical narrative imagistic technical dance’, but at a certain point we have to settle for something less than specific. My process is much like a lot of my contemporaries in that I give the movements to the dancers, make phrases and then put the phrases together or ask the dancers to put the phrases together, then I arrange those arrangements into work that has a context that I have gleaned from how the movement speaks to me. The images come from the gestural quality of the movement and the physical exertion of the performers … that leads to an emotionality that is not pasted on but comes from the body. I also sometimes give images, text or props to the people I work with and ask them to improvise. I tend to work with performers who have an innate sense of theatricality so that my process is really a collaboration with their experience. I have chosen as my main cultural influences Euro-romantic pop culture, Hollywood, and the imagery and sounds of Scottish and Japanese culture. I studied zen for nine years, six as a zen monk, which had and has a great impact on how I see movement and on my aesthetic landscape.”

Tedd Robinson s’installe dans le Pontiac, Québec, en 2005 et depuis l’été 2007, il présente de la danse dans sa grange. Robinson se fait connaître d’abord comme directeur artistique des Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dancers. Il déménage à Ottawa en 1990 et œuvre maintenant comme chorégraphe, artiste soliste et enseignant établi. Robinson est directeur artistique de l’organisme à but non lucratif 10 Gates Dancing Inc., fondé en 1998. Son travail est marqué par six ans d’études comme moine au monastère Hakukaze soto zen à Ottawa. Il est artiste de danse associé au Centre national des Arts.

« Ma formation est surtout en danse moderne eurocentrique d’influence américaine, mais mon style chorégraphique s’est développé au cours de trente ans pour devenir proche d’une expression personnelle, un style que j’ai déjà qualifié de « récit théâtral abstrait ». À présent, je pense que je le nommerai « danse-récit théâtrale abstraite imagée technique », mais il faut éventuellement accepter quelque chose de moins précis. Mon processus ressemble beaucoup à celui de mes contemporains : je propose des mouvements aux interprètes, je crée des enchaînements. Ensuite, je fais une suite d’enchaînements ou je demande aux interprètes de le faire, et je façonne ces enchaînements pour former une pièce qui émane de mon interprétation du mouvement. Les images viennent de la qualité du mouvement proche du geste et du travail physique des interprètes … cela se transforme en une qualité émotive qui n’est pas collée sur le corps mais qui en découle. Parfois, je présente des images, des textes ou des accessoires aux danseurs et je les demande d’improviser. Je tends à travailler avec des interprètes qui ont un sens inné de la théâtralité afin que le processus soit une collaboration qui puise leurs expériences. J’ai choisi mes influences culturelles principales ainsi : la culture populaire euro-romantique, Hollywood, ainsi que l’imagerie et les sons des cultures écossaise et japonaise. J’ai étudié le zen pendant neuf ans, dont six ans comme moine ; cela a beaucoup marqué ma perception du mouvement et mon paysage esthétique. »

INTERVIEW

You’re known for the striking visuality of your works, in particular your use of objects, often at an extreme scale. In the first piece I saw of yours, Lexicons of Space (1994), you performed the entire thirty-five minute work with an eight-and-a-half-foot yucca tree balanced on your head. In Red Line, you use a thirty-metre-long red sash. Your Fruit Studies, in which groups of dancers manipulate grapefruits, are legendary. Along with the dream-like flow of movement imagery, these objects give an “Alice in Wonderland” quality to your work. Could you reflect on the significance of these objects in your dances? How different is it to make a work without an object or objects like this?

These objects were not necessarily intended to become part of my work. The first Fruit Study was Requiem for a Grapefruit, which I created to be performed at a garden party, hosted by Harold Rhéaume and I, at our home in the market area of Ottawa. I did not know what I was going to perform but went out (rather grumpily as I recall) for a walk and was struck by the bright August Saturday sunlight shining on the beautiful big yellow grapefruits in the outdoor market. In a flash I saw the new work involving sixteen grapefruits, a ladder, a glass of water and “In Paradisum”, the final section of Fauré’s Requiem. I then went on to create over fifty or so studies with fruit. These studies were not sequential and I tried balancing other objects on my head … like sticks. Then a whole philosophical element came from this. I referred to it as functional movement and as minimal circus. I don’t really think of working with the objects as something separate from making my work as a whole. I have always worked within an entire universe that is filled with many things visual, and I still consider myself in this journey of exploration.

I have made many works without objects but for me they are not as interesting as the ones with objects. And yet … when I am working, I am almost always interested.

In your 2006 solo, REDD, you returned to several motifs from previous works – including balancing a branch on your head. Your series of fruit studies includes over fifty works. In several dances, you’ve used similar velvet tube-like costumes (Stone Velvet for Yvonne Ng and Robert Glumbek for example). You seem to have a conscious practice of repetition and self-quoting in your creations. How do you understand these repetitions and motifs in your oeuvre?

I don’t look at it as self-quoting or even repetition but of investigation and thematic development. The original tube dresses are the silhouette of the bottom half of a Japanese kimono. I love the simple and elegant lines that they provide and the negative space that they create in a black box setting. We see just the arms, head and feet if we choose. I used them in conjunction with Mahler songs at the beginning of the research cycle (probably three or four years) and then mostly used them for creations at LADMMI [L’école de danse contemporaine] where I have created at least five to seven works with tubes and objects. Lately I have been working with five-foot squares of material (It started, again, at Le Groupe Dance Lab and continued at STDT [School of Toronto Dance Theatre], in my solo REDD, with Old Men Dancing in Peterborough, at LADMMI (most recently with tube dresses) and in a new solo for Yvonne Ng.) The balancing of objects in my work started in the late eighties with balls painted like globes and balanced on the eye sockets of the dancers in the work Blind Angel. I have continued to investigate this idea since then. I found that I liked to watch what the body did when it was doing something functional, something other than “dancing”. I played with the subtleness of whether the body was supporting the object, usually a grapefruit, or hanging from it. In workshops it brought out ways of teaching subtlety and sensitivity in a gentle and profound way: “you” have to disappear from the performance in order for the grapefruit to balance. I refer to it as minimal circus as there is not a real risk but those watching do tend to empathize with the body balancing and feel the precariousness of the situation. Before the grapefruit workshops, I ran workshops called, “If you think you are dancing … you are not! You are thinking!” The Grapefruit workshops were an extension and explanation of the previous workshops.

You seem to have a fondness for the letter R in titles for your works, (and also a ‘k’ phoneme). Since 1996, you’ve created: Rokudo: six destinies in three steps, Red Line, Rigmarole, Recruiting Recalcitrance, Reclusive Conclusions and Other Duets, Cobalt Rouge, REDD, Rocks and The Reins, among others. Your program of works, R3, premieres this month. I’ve always wanted to ask you this: What is the significance of the letter R?

It is actually really simple. It was by co-incidence at first but then it just became simpler for me to choose titles if I was limited to “R” … another abstract thematic thread to my work. Were you expecting something more?

You work often with emerging and mid-career artists as a mentor or monitor to facilitate the development of their voices and practices. Through this work, as well as your experience with students in dance training institutions and from performances you see, can you identify a significant new way of working or quality of work in general among up-and-coming dance artists?

No and I hope I never do … I look for a unique quality of individual expression that is not trendy or trained. I am looking for work that will blow my socks off but also touch me deeply in the heart area first and then the head. In the last ten years, from among emerging creators, I have been moved by: Viliam Docolomansky’s company in Prague: Farma y Jesni; the dedication of B-boys to pure movement; Ame Henderson’s Dance/Songs; Susie Burpee’s A Mass Becomes Her; Sasha Ivanochko; Martin Bélanger; Susanna Hood; Thierry Huard Forest; and the hope and talent that I see in a few hearts of this new generation of creator/performers. Also, of course, the many choreographers from my own generation, particularly Marie Chouinard, Édouard Lock, Daniel Léveillé, Peggy Baker, Paul-André Fortier and Margie Gillis who continue to inspire and intimidate me.

In Michael Crabb’s two-part article on the demise of Le Groupe Dance Lab (published in fall 2009 by The Dance Current: online), you comment on Artistic Director Peter Boneham’s influence on your artistic development. About your own artistic direction of Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dancers from 1984 through 1990, you say: “I had a great job, … but nobody was telling me the things I needed to hear. Peter, on the other hand, does not hold back. He told me I had an innate theatrical sense but that my vocabulary sucked. He made a lot of sense.” You subsequently worked closely with Peter at the Lab for a number of years. What did you learn from him that you carry forward in your own work as a mentor/monitor with developing choreographers?

So many things! One way I tried to learn was how to see work through Peter’s eyes. The process took place over several years. He would come into the studio and sit down beside me and we would watch a run of my work. He would then usually comment gently and quietly to me the areas that he thought I should look at. I would then look at these areas of concern, acknowledge the problem and arrive at some solution that satisfied me. Eventually after a few years we would sit down and watch a run, and I would say, “Well … there is this and this and this and that!” I had by this time thought that I could watch my work through his eyes, more so when he was sitting beside me but he always, and these days still, can point to something more. He recently helped tremendously with Dichterliebe, detailing and suggesting pivotal breakthroughs in structure.

I have learned from him to be direct, say as much as I can but not hinder the process and to work with the choreographer’s feelings about the work and not with their feelings about themselves or their dancers.

Monitoring/mentoring is a most difficult thing to do well. About half the time I feel as though I make a difference and the other half I feel as though I contribute nothing but another pair of eyes, which sometimes is all that is necessary. Then there are those times when working with me was the last choreographic venture of a few choreographer’s careers. Coincidence, or did I say something to change their course? I certainly hope coincidence.

If we accept the premise that making art has a certain basis in self-expression then we had better damn well have a good idea of who we are before we start saying we are artists. Of course few of us really know ourselves when we start … but it does make one pause …

In 2005, you moved to a rural property in the Pontiac region outside Ottawa/Gatineau and have since refurbished an existing barn as a rehearsal and performance space. You host artist residencies in the summer and present performances in the space. You call it La B.A.R.N. Out of curiosity, what does B.A.R.N. stand for? And, second, it is quite clear that you offer development opportunities for artists and performance experiences for those artists, as well as audiences of the area. How does the project/place stimulate your own artistic practice and fulfill your long-term vision?

La B.A.R.N. is an acronym for la beauté, les arts, la retraite, la nature (beauty, art, retreat, nature). The reason I have invested my time into this venue was guided by others’ desires rather than my own. I wanted a rehearsal space (I created REDD in the Barn) so I built a dance floor, a platform, in the barn. Margie Gillis came up the next summer and said, “let’s do a show”. With no budget and little advertising, we made a show with our own repertoire and made a new little duet, Kilt. People came. Beer-toting ATVers, cottagers, Margie and Tedd fans from Ottawa, neighbours … people came to my broken-down barn. My planned work for the next season did not have a venue. I was hoping for a spot for it at the Canada Dance Festival (CDF) but it did not work out because the work I did for the five professional contemporary dance schools was programmed and I could not hope for two large works to be at the CDF, so I said … “I’ll do it at the barn”. I had some work done to enlarge the audience area and keep the rain out and presented Rocks that summer. The NAC sold one of the shows and put thirty-five people on a bus. We fed them lunch and gave them a very interesting day.

So out of a place that I could work, naturally and organically grew this performance space. Also I decided to start our Exclusive Intensives. They ended up being an enriching experience for everyone involved including myself. That first intensive, I remounted an older work and coached a few solos (with the invaluable help of Susie Burpee) and cooked two meals a day for eight people.

Now I see that Barn as a special venue, a really valuable asset to the dance community. Many people have come to the Barn and created work with me, created their own work, taken class with Peter Boneham and others, participated as audience members, even just performed here. People have visited here for a couple of days just to get away from their city. People have used it as a destination for cycling, knowing that good food, good art and good company awaits them. People have come here just to help out with the work that needs to be done, just because they believe in the place and want to contribute. Without really advertising it as a centre for art, people are using it more and more as a place to think about art, make art, talk about art and see art. I think it is the intimacy and the whole welcoming landscape that brings them here. Even when it rains … it is not so bad. Even with the bugs … it is not so bad. And even with me here … it is not so bad.

For your own creations, you’ve commented that you experience an increased perceptual awareness of the world and your environment during the lead up to a new process. I wonder what kinds of things you notice in this period and how that informs your movement creation?

This was a more noticeable state when I first began to create, but it still occurs, if only subtly, when I start to create. It is simple really. If you have a purpose, and it is all encompassing, you are very aware of every potential contribution to the growth and goal of this purpose. Think of a parent and child, always the child is on the parent’s mind. I think it is the same with creation. When I am about to create a new work, I am more open to what that new work actually will be, what are possible meanings of it as it progresses and before I even start I am listening for sounds (mostly music) and looking at colours and shapes (mostly in clothes and structures) in a purposeful way such that these sounds, colours and shapes could somehow contribute to or even become the pivotal aspect of the new work. I watch more closely how people interact and listen more intently to what people are saying. And, of course, I notice my own thoughts and where they lead me. Having a purpose to all of this I think is the key, no matter how uneventful something is, if there is a perceived purpose everything is more interesting. The rhythm of the sound of my pencil on the crossword page becomes something more than solving the crossword could ever become.

I usually do not prepare for any movement invention/vocabulary before entering the studio. I feel that the movement arrives with the dancers.

In August you premiered a new group work – which appears on your October program, R3, at the National Arts Centre with live music – using Schumann’s Dichterliebe: A Poet’s Love, a song cycle composed in 1840 based on the lyric poetry of Germany’s Heinrich Heine. Where Schumann’s work is a kind of retelling of Heinrich Heine’s poems, adapted for musical treatment, you propose that your work is “Schumann’s Dichterliebe as retold by choreographer Tedd Robinson.” What drew you to work with Schumann’s music? In what ways is the work a “retelling”?

I see Schumann’s song cycle as a musical marriage of Heine’s work and Schumann’s music. There were many poems in Heine’s Buch der Lieder, and Schumann chose twenty then narrowed it down to sixteen. He selected a viewpoint and told a story. My re-telling is imagistic and non-narrative. It is coincidental and symbolic. It is a way to listen to Dichterliebe from another point of view without sacrificing the original (at least that is my intention). I studied Dichterliebe as a music student at York University in the seventies and have followed many musical interpretations of it since then. It has comforted me when I was lovelorn and I am sure each time it is played, its power is increased with all of those listeners who receive comfort in it.

Your R3 program is billed with reference to your interest in the nineteenth-century salon, an intimate and private environment for readings, performances, intellectual development, cultural exchange and study. Do you perceive a parallel between your hosting of residencies and performances at La B.A.R.N. and the salon? What values and potential engage you about this kind of setting? How will the salon context inform the performances of R3?

I had not thought of the barn in that way but now that you mention it, I suppose there is a co-relation. I have usually played in smaller theatres and have purposely done this as I feel that my work is better transmitted more intimately. This was the idea behind the activities here at the Barn: magnificent performers performing intimate work for a small number of spectators. Also, once I had experienced it, the idea that we work together all day then eat together in the evening has always seemed the only way a work should be created. There seems something quite civilized, yet adventurous about it. The Exclusive Intensives work the concept much more in that I bring together emerging dancers and choreographers, usually from across Canada, but last year we had participants from Ireland as well, and we all live together (they do at least, as I still live at my house across the road from the cottage where they are), and share food and stories and experiences. As far as I know many participants still keep in touch. It is a small way in which this country of ours can become smaller … through shared experiences like the Intensive (any intensive for that matter but because we have only a small number of students (six to eight)) it becomes both exclusive and intensive, intimate and lasting.

So this idea of shared experience is how I view performances as well. There is something very intimate and trusting about sitting in a dark theatre with a lot of strangers and watching people in various concentrated and open states … there is something soothing and hypnotic about it, but also adventurous as we really don’t know what will happen and how we will feel about it.

R3 is hopefully going to work in this way but I am never sure exactly how it will be until it is in the theatre.

I do have an aversion to telling what will happen or what I intend to happen or what I wanted to happen or what people should expect to see … as that totally takes away the adventure. People are most comfortable when they know what to expect … because then there are no surprises and the work either lives up to what their expectations were or it does not. But really the upper controlling hand, in my opinion, ought to be with the artists. An audience member must either trust in the journey or not. I would rather have twenty adventurous audience members who may “bravo” or “boo” than 300 people who have come because they have read exactly what it is they are about to see and approve of it.

In R3 you’re presenting excerpts of two past solos, Rokudo and Relic, as well as premiering a new one. I’m curious about your experience inside solo performances. You’ve commented in the past about the slipping and sliding transitions between personae or characters and how you learn about a work from within. How does this learning influence subsequent remounts of the work? How much are your solo works autobiographical in some sense? (I’ve heard that you frequently have a “Tedd” character in your group works. Is this true? If so, why?)

Hmmm, you have done some homework. I am now in the process of trying to figure out how my solos come about. It is not that it is mysterious but it is a long process and sometimes I forget when and how an idea or image appears. I have been for the last few years working on bringing my different processes together to become more whole. Throughout the last thirty years I have kept quite a large rift between how I work in the studio alone on myself and how I work choreographing on others. Alone I have always worked through improvising and recording as much as I could on video, and then after a few months of ecstatic and inane dancing, an image will drop into my exhausted body, something simple, something I can remember (as I have a terrible memory for steps) and more to the point … something poignant. When I choreograph for others I do not have the time that I give myself for my solos. Also I usually work with extremely talented dancers and I want to make them do the things that I can’t possibly do – a dichotomy that does not serve the work I think. So I am working towards changing my ever-evolving process.

The nature of my solo work is really about remembering to accomplish given instructions in an order, on musical cues. At least that is what it is like at the first run-through. During the subsequent runs and particularly the performances of the work it seems to begin to breathe within me and I find the road, and where I am going, but along the way I lose “me” to the performance of the work. I used to and still recognize the entity I called “the little guy” who I would say is my performance life force … the glint behind the eye … the person Tedd is too shy to be … the flirt, the lover, the entertainer, the handsome man, the innocent geisha, the stripper, the vampire and the angel. These archetypal seeds were instilled in me when I was a child (a kid lost in a dream world, hence perhaps your sense of Alice) but then planted, watered, fertilized and nurtured by [iconic British choreographer/performer] Lindsay Kemp who, in a mere eight weeks of study and association throughout May, June and July of 1978, changed my aesthetic life forever. I have not seen him since and there has not really been a reason, although I have always thought that I would like to seek him out and just say “I thank you Lindsay”, even if he did not remember me, which apparently he might not, but with some prodding (probably a lot) … he might.

My solos are autobiographical in nature, but are rooted in the stories of my aspirations and wonderings about influences and curiosities and those energies we may refer to as past lives. They are fantasies based in “tedd-fact” and I don’t think that is much different from anyone else who creates.

(Sometimes but not always, there might be a character in my group work that would be the role that I might see myself performing … it is usually the one that does not move so much. Rob Abubo was that me in the many works I created at Le Groupe while he was there.)

*Note de la traductrice : en français dans le texte

Tedd Robinson, 10 Gates Dancing, presents R3 from October 28th through 30th at the National Arts Centre, Ottawa. | Tedd Robinson, 10 Gates Dancing, présente R3 du 28 au 30 octobre, au Centre national des Arts, Ottawa.