Sound and visual artist Gary James Joynes’ original installation Broken Sound was shown at dc3 art projects in Edmonton last spring. Dancer/choreographer Brian Webb approached Joynes about collaborating with the installation, and Broken Sound2 was developed.

The original set of Broken Sound remains in this version. It consists of high-res video of rotating burned and broken copper voice coils from the inside of speakers destroyed by Joynes’ Chladni plate pieces of the past eight years (Chladni plates are square metal sheets that demonstrate patterns of sand responding to sound frequencies). Joynes projects the glowing coppery fractured lines onto four twelve-foot vertical projection panels in a dark and fog-machined room. The projected lines travel downward, giving the viewer the illusion of a slow ascension. In many ways, the Broken Sound installation is much more interesting that his Chladni plate pieces, as these projections transcend their original medium, as opposed to just close-ups of a well-known acoustics experiment.

At age sixty-five, Brian Webb has examined aging, the failing body and the failing mind in his recent work. Conversation and intimate gesture are part of Webb’s narrative when he speaks about his work. Webb was very interested in finding a way to bring these ideas together with Joynes’ installation.

In Broken Sound2, the entire audience is invited onto the proscenium stage of Timms Centre for the Arts. Webb and Joynes sit facing each other in the middle at a table. Dividing them is a massive console of Joynes’ audio and video gear, including a large monitor, a large mixer and a modular synthesizer. The audience sits on benches and cushions around the performers and become enclosed within the stage space and the projection panels as the curtain closes. Webb is dressed casually in neutral toned jeans and a sweater, while Joynes is dressed formally in a black suit. Webb introduces the concept of shared experience and meaning in conversation and in performance. He returns to his chair across from Joynes and recalls for him a meaningful audience experience, frequently shifting his position in the chair, often slouching to think and remember or straightening up to make a statement. Joynes sits plainly at the helm of his console. General stage lighting lights the performers, and the projection panels stay dark throughout the lengthy conversation section. Speaking into large microphones, Joynes alters or “breaks” the sound of their voices with multiple effects as they speak, sometimes giving them a mechanical quality.

The conversation suddenly redirects into a slow back-and-forth about their aging, dying or deceased parents, which lasts about two-thirds or more of the performance. Both indicate a lack of tenderness from their parents early in life but were put in the position of dealing with intimacy as they aged. Bodily functions, particularly defecation, are a strong fixation in the work.

First, they exchange stories about their dying mothers, currently in hospice or nursing care. Second, they exchange stories of their fathers, both now dead, and their presence in their fathers’ final hours. Webb remembers holding his father up in a standing position after defecating dried blood so his mother could clean him. He recalls this as a slow dance on his father’s final night. Joynes had sung to his father as he died.

The conversations between Joynes and Webb have distinct styles. Both discuss their parents’ vulnerability. Webb is formal yet weary, his emphasis on indignity. Joynes is informal and emphasizes his importance to his parents, and at times he seems oddly giddy. Webb maintains clear eye contact as Joynes shares his stories. Joynes is frequently distracted by his console as he plays with the voice effects.

After about forty-five minutes, as the broken voices trail off and the lights dim signalling the transition to the original installation of Broken Sound, Joynes starts the music as he and Webb start moaning harmonically into their microphones. Webb pushes back his chair, the projections start panning and Joynes fires up the fog machine.

Webb slowly circles around the tables with Joynes backing these movements initially with sustained vowels and diphthongs, a signature of Joynes’ earlier vocal work. Sounds from the original Broken Sound installation follow — layered tones likely associated with the frequencies that fried each coil, as they glitch for a millisecond to a different tone along with a change of video on the panel to another coil. Webb stands in the paths of the projections performing broad upper body movements or standing erect as the lines pass over him. He wanders through the space as if lost, a characteristic of Webb’s work of the last several years. At times he stops to look audience members in the eye. Sometimes he seems surprised by his own hands, punching them with anger and fear.

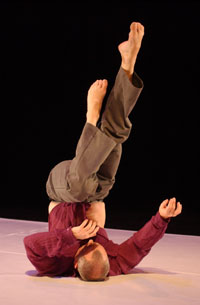

To close the piece, Joynes slowly stands, leaves his console on autopilot and circles around the tables. He and Webb meet, and after a tentative approach, embrace and slow dance as the last linear images pan by.

People usually survive their parents and are often responsible for helping parents through their death. As such, this piece could be quite moving and pertinent to some audience members. For others, it might be perceived as self-indulgent. Aside from the parallel of sound and life, the two sections seem artistically very separate. That said, each artist clearly maintains his own voice in the collaboration and seems likely to continue the conversations outside the theatre.

Tagged: Choreography, Contemporary, Interdisciplinary, Performance, AB , Edmonton