The story of Cinderella and her glass slipper is as old as the hills. Although versions of the story are a cultural phenomenon around the world, we in the West are most familiar with Charles Perrault’s 1697 fairy tale, Cendrillon, ou la petite pantoufle de verre. That or Disney. Personally I grew up with “bippity boppity boo”. And long before my son turned “gangsta”, he too was mesmerized by the singing mice and pumpkins of the animated classic.

I suspect James Kudelka was also a fan. His newest full-length ballet for the National Ballet of Canada has the same kind of sweet loopiness and humour. This work, set in the Twenties or Thirty-somethings and performed to Prokofiev’s famous score, is enchanting on all levels, with just enough of a nod to the dark side of the human psyche to make it vintage Kudelka.

The ballet opens as expected, with Cinderella (danced on the evening I attended by a very limber Sonia Rodriguez) polishing something by the hearth and dreaming about love. A bizarre dream sequence that erupts from a smoke-filled fireplace signals that there could be surrealism ahead. Weird little girl angels turn out to be adults on their knees; they attend at a premonitory wedding before the dream dissolves with the arrival of Cinderella’s famous stepsisters.

As portrayed by Jennifer Fournier (the snooty one) and Rebekah Rimsay (the nerdy one), the stepsisters provide comic relief for the duration of the evening, raising laughs whenever they appear. In this is a skillful blend of comic acting and real choreography, the pair is delightfully up to the task. Rimsay, with her oversized glasses and carefully sketched naiveté, is a bit of a scene-stealer, never breaking character once. Fournier is her more-stately straight man. Their comedy is unmatched until Victoria Bertram makes her star turn as a tippling Stepmother – the woman has a gift for taking her time to cross the stage, milking every tipsy step for guffaws.

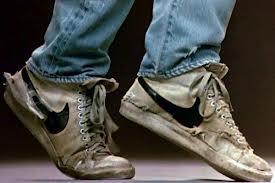

As tempting as it is to let the comedy just wash over you, a close examination of Kudelka’s movement, particularly from the ankles down, provides ample reward for the sharp-eyed student of choreography. The pointe work is extremely imaginative and Kudelka uses it to define character as well as to move the story along its traditional shoe fetishist lines. The stepsisters stutter en pointe therefore, or flex their feet in deliberately unpleasing ways, reflecting both inner and outer ugliness; pure-of-heart Cinderella, who is barefoot for a good part of the ballet, performs a heart-breaking dance with one pointe shoe that speaks volumes in terms of narrative and sub-text (is this Kudelka’s commentary on the seldom examined code of ballet footwear?).

Anyway, back to our story. Preparations for a big royal party are a chance for Kudelka to keep it busy and further his flapper/early thirties scenario. Complete with a foppish dress designer and assorted minions, these scenes also contain some weird touches – for example, a measuring tape becomes a noose around the neck of a stepsister as she’s fitted for a gown – that suggest Kudelka’s own ambivalence towards the saccharine sweet Western interpretations of what were originally complicated and often blood-curdling fables and myths. The footwork here is detailed and probably wickedly difficult to perform – runs en pointe and spins en pointe with feet alternately flexed and stretched. Later, in the garden sequences (the equivalent of cartoon Cinderella’s dressing up by birds and mice), the transformations and the melding of Nature and Civilization continue. Here, the dancing is classically feminine yet full of interesting deviations from the traditional, especially in the port de bras. Kudelka slows the movement right down, which I think makes for a new found clarity of line in his work. This made it possible to see emerging talent that much more clearly. Tall red-haired Julie Hay was a standout as the languid Petal on the evening I attended.

The garden dances present a magical preparatory build-up to the centerpiece of the ballet and the story – the Prince’s ball. Here, the dancing pre-Cinderella’s arrival is vaguely jazz era, especially for the men. The stepsisters continue their comic turns, alternately vamping and tippling, each mode with accompanying flat-footed or bizarre movement vocabulary (it’s as if Kudelka sent them both to study at Monty Python’s Ministry of Weird Walks). Rebekah Rimsay’s neo-Theda Bara routine is a riot.

When Cinderella arrives, it’s via a giant golden flying pumpkin, a show-stopping tour de force by designer David Boechler. At this point we’re half way through the ballet and Cinderella still hasn’t connected with her Prince (played on this program by the impeccable Guillaume Coté). Part of the challenge of this story is keeping the interest in the two characters high in anticipation of the inevitable. When the pair finally does get together it’s with a duet that’s sinuous and low-key. The dance builds to a series of showy lifts and then turns vaguely surreal as the clock runs out on Cinderella’s trip to the good life. The pumpkin-headed timekeepers return (this is my favorite quirky Kudelka innovation) and the spell wears off rapidly.

With Act Three – The Search, Kudelka reinstates some of the Prokofiev score that many choreographers choose to trim. He uses it for a trip around the world sequence (a ballet convention not much seen in contemporary times) in which Coté and his four officers (Nehemiah Kish, Patrick Lavoie, Richard Landry and Jean-Sébastien Colau) travel the globe in search of the lady-who-will-fit-the-glass-slipper. There’s lots of delightful business here – from an Inuit wrapped in a Hudson’s Bay blanket to a one-legged woman to a mimed car scene – all performed fast and furious with special attention paid to comic detail and footwear. Eventually the whole entourage lands at Cinderella’s house and, well, you know what happens.

The proceedings wrap up with more ponderous yet still lovely duets as Cinderella and her prince re-discover each other and then, following the path of true love, these dances segue into the wedding. Kudelka gets in one last (very contemporary) point: Hazaros Surmeyan, who has played a snap-happy paparazzo throughout the second half of the ballet, tries to get a shot of the happy couple settling into a post-nuptial tête-à-tête. The prince shooes him away and the curtain falls. True love, Kudelka seems to be suggesting, is a private matter, its real intimacies not up for public scrutiny.

Tagged: Ballet, Performance, ON , Toronto