Toronto Pride, July 3rd, 2016. For the first time, a sitting Canadian prime minister, Justin Trudeau, marches with members of Canada’s LGBTQ+ community. Sporting a pink shirt and waving a rainbow flag, self-proclaimed feminist Trudeau corporealizes our “benevolent” multicultural nation as the futured body of his father and former prime minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, who claimed Canada had no business in “the bedrooms of the nation.” In solidarity with Queer and Trans community members, Black Lives Matter Toronto (BLMTO) halts the festivities for thirty minutes. Via a sit-in, they call out the participation of uniformed Toronto police officers in the parade while systemic racism and anti-Black violence persists. The younger Trudeau, ghosted by his father’s pirouettes, is a prism refracting a rainbow of pinkwashed queer bodies normalized and bid welcome inside Canada. BLMTO’s stopping of Pride’s smooth, forward flow illuminates those Black and Brown bodies that are queered as subhuman and evicted from the nation.

In their disruption of Pride, BLMTO effectively spotlights who moves with relative freedom and who does not in the land now called Canada. Working within the grain of the Pride “aesthetic,” members of BLMTO mimic its processional rhythms and monitor its pulse until the time is right to flip the script and stage their intervention. BLMTO’s harnessing then subverting of Pride’s joyful contagion wields a powerful irony. As performance researcher Naila Keleta-Mae describes the sit-in, “Black Lives Matter is dramatic, unsettling, inconvenient. That’s the point.” Pride-goers feel themselves draw to a standstill. Voices quiet. What to some feels like their party being crashed is for others a sophisticated disruption of what philosopher Jaana Parviainen calls “the characteristic motion embedded in a certain place or location.” BLMTO’s receptivity to and transgressing of Pride’s multiple frequencies reveals the body’s agency and intelligence – its capacity to act.

As BLMTO co-founder Rodney Diverlus explains in Canadian Theatre Review, protest materializes in blockades, occupations, marches, die-ins and surprise actions – physical interventions accomplished with and through bodies. Accompanied by music, rapping and spoken word, this repertoire Diverlus calls “politichoreography” follows an open score. Through sequences such as kneeling with their hands up in surrender (to memorialize Mike Brown) or lying en masse, BLMTO remembers their dead at the same time they insist upon Black futurity. “This gesture exposes the injustice of police violence against Black bodies,” Diverlus explains. “We are killed even in acts of surrender. Further, the gesture refigures surrender as resistance.” Regardless of tone, a synergy exists between choreography and protest in the strategic repertoire deployed by Indigenous people and People of Colour to survive.

It makes sense then that protest is, at its root (and according to Wikipedia), “an expression of bearing witness on behalf of an express cause by words or actions with regard to particular events, policies or situations.” I’ve started with BLMTO’s sit-in at Pride not just to highlight the body’s agency but to demonstrate how choreography, as the arrangement of physical, social and political space, disentangles dance from its moorings as a lofty and superficial thing. Choreography distills its essence as human movement. As genres of human movement, dance and protest are particular and rigorous forms of labour that entail the work of remembrance and caring for difficult histories, memories and stories.

Embodying complex histories through the body offers a different understanding of time and space, typically though of as linear and finite. As well, when we are are directly addressed by human bodies who bear witness to or survive an event, it adds a concreteness to their testimony because they are their own material evidence. I have felt viscerally onstage how, through our bodies, we carry and care for the stories of others. Dance offers a place to activate the past in the present where it emerges as dynamic, unfinished and, therefore, changeable. This is also the case with other projects that I’ll explore – namely The Holodomor Project by Verba Ukrainian Dance Company (Winnipeg), Meridian by Chai Folk Ensemble (Winnipeg), Bearing by Signal Theatre (Toronto) and Blackout by Tableau D’Hôte Theatre (Montréal).

I have been able to spend substantial time with many of the artists I move with in these pages – as a dancer, director, choreographer and performance researcher. They each encompass some of the Indigenous, settler and diasporic identities that coexist and collide within contemporary Canadian society – a society premised on neo-liberal multiculturalism where the policing of difference masquerades as “diversity.” Although clustered within three provinces, the companies elude the arbitrary borders of the nation-state. Instead, they send breath across Turtle Island and internationally to speak to larger issues of colonial violence, systemic racism and cultural memory that are personal, universal and ongoing.

By looking at these staged choreographic performances as acts of protest, I’m able to resist the cleaving of art and culture from everyday life, to sidestep elitist divisions of dance as “amateur” versus “professional” or “folk” versus “concert dance” and to underscore the continuous flow between art and activism, the theatrical and the quotidian. In other words, protest enables me to swerve past what dance is and look instead at what it does politically.

The Holodomor Project – Verba Ukrainian Dance Company

According to Inga Bekbudova and Andrea Roberts, Ukrainian dance in Canada has been a means for settlers and new immigrants to celebrate diasporic identity. Such is the story of the Verba Ukrainian Dance Company. Like their namesake, the willow tree, Verba is not afraid to shed convention to foster new dance ecologies. There is no board or artistic director calling the shots, and decisions are made collectively. Verba commissions guest artists to expand their repertoire, but the studio is equally a creation lab for the dancers to explore their choreographic voices.

Based in Winnipeg, Verba was founded in 2011. Even though it was still a fledgling company, Verba soon undertook The Holodomor Project: 80 Years of Eternal Memory, which premiered in 2013 – the eightieth anniversary of the genocide of millions of Ukrainians as well as Russians, Poles and Moldavians. Translated as “killing by hunger,” the Holodomor was devised by Stalin’s Soviet government in the USSR. From 1932 to 1933, food production in Ukraine was systemically rerouted to foreign markets, and the people, a third of them children, were left to starve. Even though news of the famine was widespread, and the world knew it was happening, Canada has only recently legally recognized the Holodomor as genocide and a crime against humanity.

Wanting to be respectful of this difficult history, Verba made the decision to tell the story through a contemporary dance aesthetic instead of Ukrainian dance. Co-founder Johanna Chabluk explains, “The tragic subject matter [of the Holodomor] is not at all typical of why Ukrainians dance. Usually, [for us] dance is celebratory.”

The Holodomor Project was co-choreographed by Winnipeg artists Claire Marshall and Marijka Stanowich, with Stanowich conceiving the piece. In preparation for this project, the dancers researched the Holodomor and aftermath and contributed images that spoke to how this knowledge resonated with them. The piece centres on a young woman who seeks desperately to live but inevitably succumbs to her hunger. The dancers bring to life the memorial statue in Kyiv, Ukraine, of a little girl with braided hair in a peasant tunic dress. Stage makeup and oversized costumes create the illusion of gauntness. They move through vignettes of carrying each other, doubling over in agony, praying or swaying in the throws of starvation. The dance, music and archival images of emaciated bodies invoke in the audience a visceral understanding of starvation. But the brutality of the Holodomor is tempered by the flowing choreography and the humility with which the dancers tell the story.

Because contemporary dance was a new way of moving for many of the dancers, the company began training with Marshall at least six months prior to their choreographic process. “I remember working diligently towards feeling ‘grounded,’ ” reflects co-founder Jenn Doroniuk. “Ukrainian dance is very upright and held, and for the majority [of the dancers] this was a brand new way to move and feel. Emotionally, I recall feeling extremely vulnerable; however, this was counterbalanced by being surrounded by such a trusting and close-knit group of friends. I think we all truly grew as dancers during the process.”

As the dancers surrendered their upright postures to gravity and weightedness, their willingness to be vulnerable and move into unknown physical (and emotional) territory is evidence that The Holodomor Project is a labour of love. The dancers emulate bodies lying in fields and underneath trees and the catching of bodies as they fell. “During the Holodomor this would have happened to thousands of families in Ukraine,” explains dancer Kristina Frykas. “To relive this and honour them in rehearsal and shows was very difficult but important.” Even though the dancers are in a proscenium theatre in Winnipeg, they do not merely “represent” Ukraine. They enact Ukraine and, by proxy, the Holodomor into the space.

The performance ends with the dancers in a line holding candles. They flicker in the dark like stars. The memories of the millions who died by starvation, some of whom are close relatives, are danced out from the recesses of national forgetting. Carving air through high lifts and falls, the Verba Ukrainian Dance Company creates infinite mnemonic space for this history through the physical space they make with their bodies. To those who suffered such cruelty, their dance offers comfort, dignity and, ultimately, nourishment.

Meridian – Chai Folk Ensemble with The Black Sea Station and Verba Ukrainian Dance Company

Winnipeg is also the home of the Chai Folk Ensemble, which is turning fifty-five this year. Chai is Hebrew for “alive.” The group began in the basement of the late founder, Sarah Sommer, and is now an internationally acclaimed troupe of dancers, musicians and singers. Although “Jewish dance” often indexes the hora (Romanian for “circle”) or people being hoisted on chairs in celebration, in reality it encompasses any culture that Jews have touched across the hemispheres.

Indeed, to perform Jewish and intercultural dance is to embody a complicated history of a people forced into exile, who have long traversed the world looking for home and place. Yet through these difficult wanderings, sacred traditions haven’t just been kept alive but have flourished.

Because Chai represents the Diaspora, the troupe is intercultural to its core. It offers new immigrants a community and way to keep their homelands close and has established partnerships with local and international artists. Also, you need not be Jewish to be a part of Chai. The company embraces technically strong, passionate artists who will fully realize its vision. It is also the perfect balance for those who don’t pursue a professional career but desire to express themselves on a high level, which is how I found my way into the company as both a dancer and dance director. The young adults who dedicate their time to semi-professional performance balance rehearsals with studies, professional careers and families. Although Chai has a board and is led by Artistic Director David Vamos, it is the work of a multitude that includes the current dance director and choreographer, Rachel Cooper.

The Meridian show was gifted to Chai by Israeli choreographer and longtime associate Shai Gottesman. It involved many moving parts including Chai, klezmer band The Black Sea Station and dancers of the Verba Ukrainian Dance Company, whom I invited because of their groundbreaking work in The Holodomor Project. As a Ukrainian-Canadian myself, I was curious as to how Meridian might be a productive space where our cultural histories, each ghosted by catastrophic loss, could dance in coalition.

We performed Meridian on November 17th, 2015, in Winnipeg. Running ninety minutes in length, it featured twelve pieces. Balkan music came alive in a 7/8 time signature. Israeli and Arabic notes collided in a sensuous duet while a Romanian village of eccentric characters and rhythm patterns unleashed a frenzy of joyful activity. The show took a sombre tone with pieces that pray for Holocaust memory and those who live with mental illness. In the finale, during a section called Different Rhythm, Turkish and English notes punctuate an electrifying village celebration. Instead of being separate parts, the musicians and singers were choreographed to move organically through the dancers.

Verba’s contribution, choreographed by Jared Laberge and Kiersten Knysh, is called Arrivals. The song they chose, The Black Sea Station’s My Dinner at Schwartz’s, sounds like a train station at the turn of the century. The piece erupts into chaos as new immigrants and workers make their way in the world. Watching Ukrainian dance to klezmer music was, to me, witnessing a breaking of the conventions of essentialized notions of identity and ownership over culture.

Initially, my reaction to the title Meridian conjured borders that enact violence. But soon, as I felt the circulation of energies moving together, I felt instead a physical and sonic harmony. Embodying Meridian allowed me to see how music, made palpable through musician, singer and dancer, makes new worlds. As Chai and Verba worked together in the studio, we discovered commonalities in our movement vocabularies – that a triplet step, though known by different names, shared the same intention. In so doing, meridians were reimagined as pathways of becoming instead of as borders.

Chai has continued the work of intercultural solidarity in concerts such as Ancient Roads (2017) and Woven Threads (2018). Chai and the Rusalka Ukrainian Dance Ensemble, who first joined forces in 1999, will travel to Israel and Ukraine with their Hora Hopak Tour this July.

Bearing – Signal Theatre

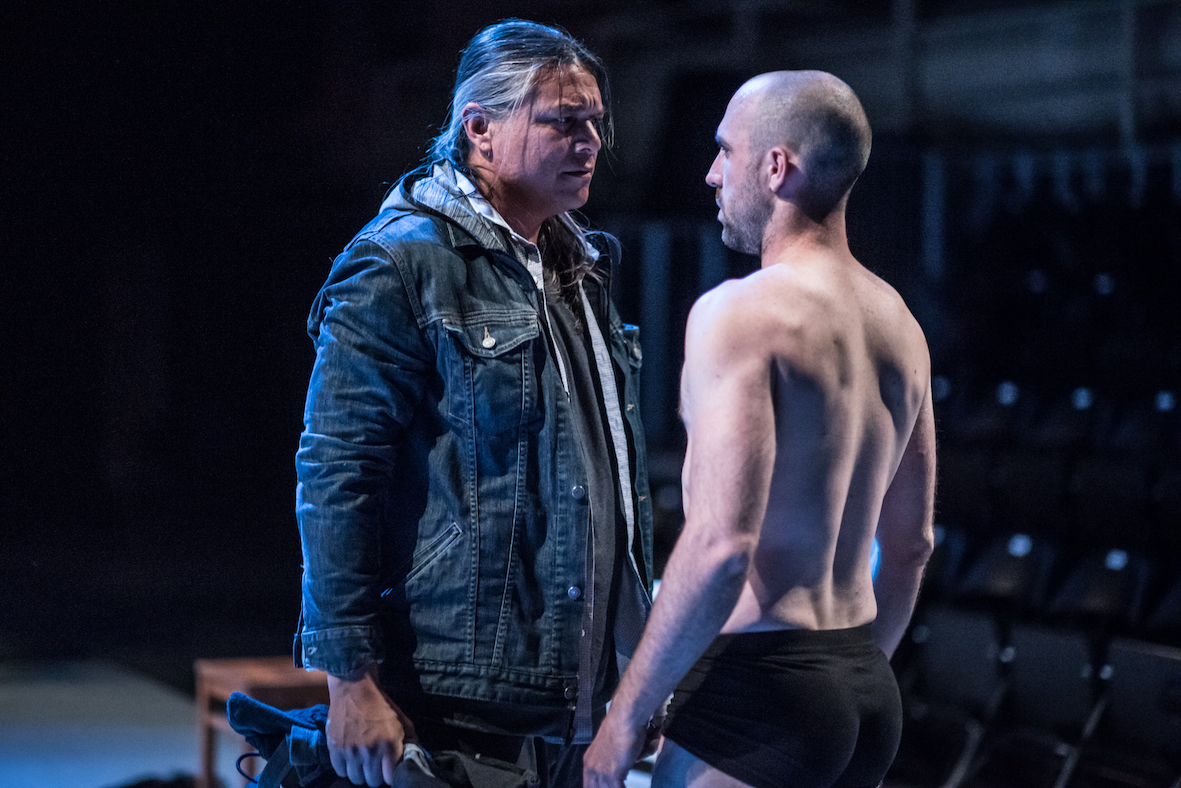

Based in Toronto, Signal Theatre is Indigenous led, interdisciplinary and intercultural. Michael Greyeyes (Plains Cree), Yvette Nolan (Algonquin), Brittany Ryan (Métis-Chinese) and Nancy Greyeyes (Polish and Russian settler heritage) are its four pillars. But Signal’s structure is fluid. Founded in 2010, Signal Theatre creates work that examines Indigenous experiences of colonial violence, intergenerational trauma, war, PTSD and the fragility of memory. Through the layers of dance, text and music, Michael Greyeyes and Nolan carry and carfor the experiences of their parents who were residential school survivors. Because process is just as important as the final staged product, Signal Theatre’s repertoire is a cumulative unravelling of genealogies that are as personal as they are political.

Signal works with a cast of actors and dancers who represent contemporary Canadian society. In so doing, they refuse to perform ethnicity in a way that we might associate with a stereotypically Indigenous look and sound. The dancers and choreographers work within the grain of what they do best, concert dance, to create work that invokes the land and feels northern – stark, cold.

In Nôhkom (My Grandmother), Nancy plays Michael’s paternal grandmother, Margaret (“Maggie”). The correlation is personal: it was to Nancy that Michael’s father, George Greyeyes, began to tell stories about residential school. It is the knowledge that she cares for that makes her equipped to play the role. In creating her final solo, Nancy uses delicate, balletic moves to express Maggie’s soft voice and laughter.

Bearing, Signal Theatre’s 2017 dance opera, reckons with Canada’s residential school system – those schools where 150,000 Indigenous children were incarcerated. Co-produced by the Luminato Festival, it frames residential schools and the forced removal of children from their families and communities as a system in which all those who live on this land are bound, where Indigenous and settler peoples are characters enmeshed within the continuing story. And although the term “Indigenous” can act as a term that homogenizes the specific cultures of First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples on Turtle Island, the experience of residential schools is familiar to many of them who reside in Canada. Instead of giving Canadians another history lesson, Bearing asks the public to embody it in the present tense. “Bearing poses a simple question,” explains Michael. “What do you do when you come into knowledge? If you can understand this history on a visceral level where it affects you, where you feel gut-punched, what do you do now? And if you do nothing, you’re no better than the people who did it 120 years ago. That’s what Bearing is. It asks you to know – to bear knowledge.”

The performance space for Bearing is at Toronto’s Tanenbaum Opera Centre, which offers seating on three sides, with the musicians and singers on a raised stage on the fourth side. In the centre is a stark white, ground-level dance floor. It resembles a hockey rink – that quintessentially “Canadian” space wherethe country gathers and is re-indoctrinated into national pride. Bearing’s hockey rink, in its severe whiteness, brings to centre ice two sides of Canada – the diverse settler nation and the colonial state that brutalizes and absorbs Indigenous peoples, who are themselves complex, multicultural nations, into a rights-based framework. With forty-six performers in total, it is one of the largest Indigenous-led productions mounted on Turtle Island to date. It is epic, as is its subject matter.

Viewers are directly addressed by three Indigenous performers who play a family fractured by the forced removal of children and their experiences of abuse in residential schools. They are mother Mary, son John and daughter Annie. Aria Evans, who plays Annie, is an example of how Signal brings their ancestors into the room. In fact, the character is named after Evans’ great-grandmother. In many Indigenous cultures, time is circular and so healing is multidirectional – radiating backwards as well as forwards. The artists, as the futured bodies of their ancestors, care for their relations in real time.

A cast of six settler dancers play Canadians. In Bearing the settlers step inside of Indigenous experiences of Canadian colonial violence. Instead of the Indigenous characters teaching the Canadians, as is so often expected of them, it is the Canadians who do the work of knowledge-seeking through fiercely physical contemporary dance. Within Signal’s mandate to work collectively, they work with dancers who are themselves strong choreographers. To generate movement, Nancy, who became the lead choreographer for Bearing, had the dancers read passages from Richard Wagamese’s book Indian Horse, look at paintings by Alex Janvier and view Nolan’s imagineNATIVE film A Common Experience, directed by Shane Belcourt. The movement the dancers contributed in response was, as Nancy put it, “mind-blowing.” She then connected these responses together. Empowered by mutual trust and respect, the dancers bear some of the weight of this difficult knowledge.

In three acts, Bearing includes movements from Bach, the late Québécois composer Claude Vivier and Spy Denommé-Welch and Catherine Magowan of Unsettled Scores. Although Signal Theatre incorporates European music to aurally invoke the colonial presence on the land, they also reject the assumption that classical music belongs only to the colonizers.

In the work, the Canadians enter the space clad only in their underwear. They are reluctant to be vulnerable and engage with difficult knowledge. The dancers pull on and off abstractions of a nun’s habit, a priest’s robes, a school uniform, a lawyer’s suit and clothes that they would wear in everyday life. The dancers assume the experiences that haunt the skin of survivors. Telling me about his research for 2012’s A Soldier’s Tale, Michael says it “helped us set up really what happens when people touch the costumes. It’s immediate not historical. How people react to the past frames how we should look at the past. So, we performed disgust, we performed diversion. And that was happening in front of the audience in real time.”

With Bearing, Signal Theatre protests the notion of spectatorship as passive. During the performance the Indigenous family members move into and take seats amongst the audience, making them move aside. Feeling their presence so close to us, we find ourselves sitting straighter under their surveillance. We feel them watching us watching our onstage avatars fumble their way through a residential school classroom. We feel viscerally that there is no more room for indifference. Projections of archival photographs of a school, students and English scrawled across a chalkboard are projected horizontally onto the dance floor. It is disorienting, dizzying – making its audience plunge into history such that we lose our grasp on the Canada we thought we knew.

Through extensive repetition of movement, the dancers underscore the closed loop of trauma where the past subsumes the present – why survivors cannot just “get over it” and “move on.” The Canadians, as the futured bodies of their colonizer/ invader ancestors, realize their complicity in the colonial relationship as they struggle through ugly feelings of guilt and denial. And although the work ends on a hopeful note, it does not fabricate a sense of closure as upheld by dominant reconciliation narratives. Like the wreckage that ends Act 2, conciliation is messy and unfinished. Bearing spells out, through the dancers’ rigour, the exhausting work of inheriting difficult truths where once we accept this terrible “gift” of knowledge, what do we do with it?

Blackout – Tableau D’Hôte Theatre

Founded in 2005 by Mathieu Murphy-Perron and Mike Payette, Tableau D’Hôte Theatre (TDHT) thrives on intercultural dialogue and collaboration. Acclaimed for their innovative storytelling, TDHT nurtures both established and emerging Canadian playwrights. They interrogate notions of identity and nationhood and give space to those voices cast to the edges of the cultural mosaic. At a local level, TDHT injects English-Canadian plays into Montréal’s theatrescape. In so doing, the company brings together Franco, Anglo and Allophone audiences.

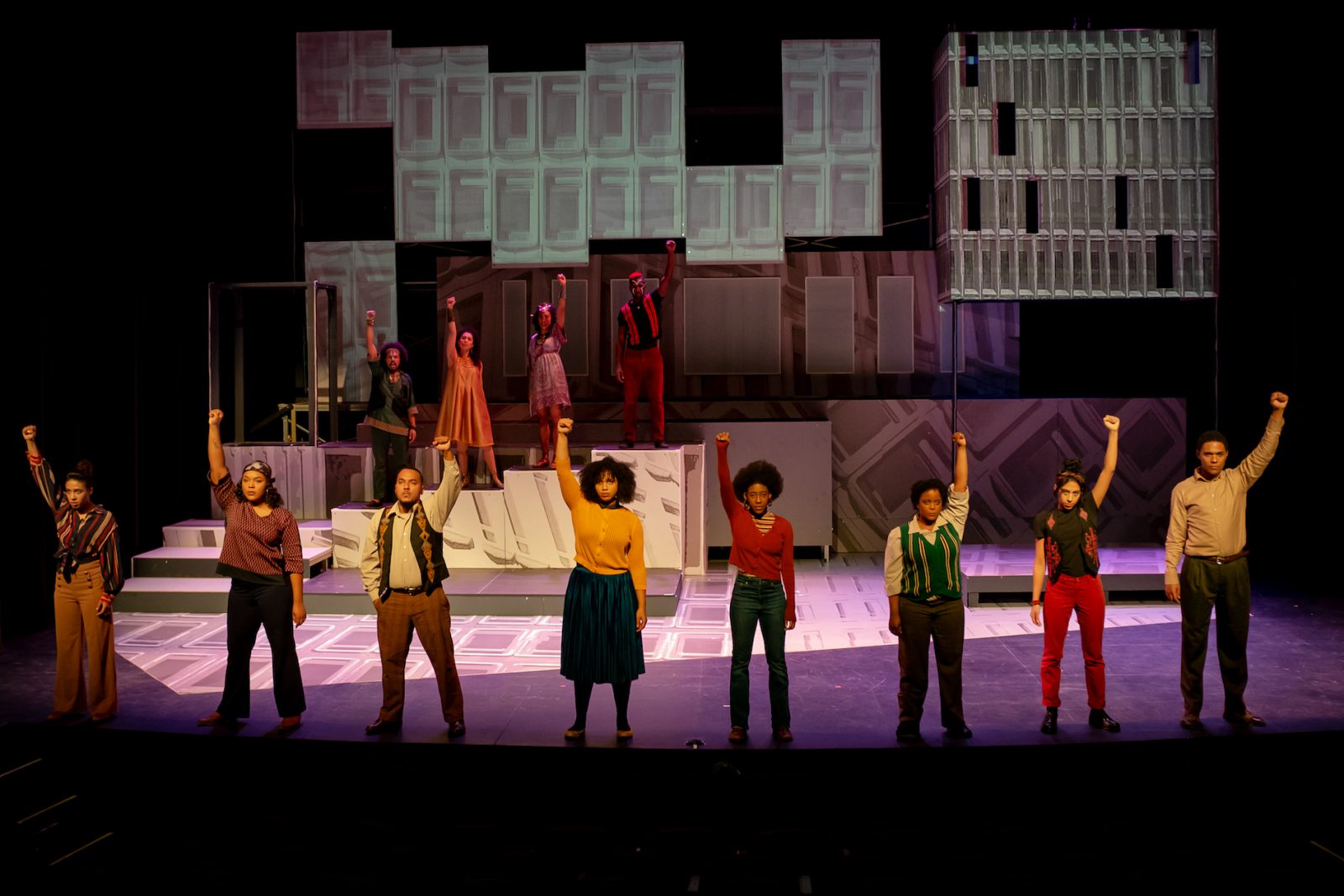

Blackout: The Concordia Computer Riots re-examines the events otherwise known as “The Sir George Williams Affair” when, in the winter of 1969, Black Caribbean students protested institutionalized racism at what is now Concordia University. One of the largest student uprisings in Canadian history, the protest that began as a sit-in is now associated with nominal property damages that obscure the human costs to the students, many of whom were arrested for merely fighting for their right to an education without discrimination.

Fifty years later and ten storeys below where it happened, Blackout had its world premiere in the D.B. Clarke Theatre, named after the acting principal at the time of the uprising. TDHT assembled a team of nearly twenty directors, designers and dramaturges to create Blackout. The cast of twelve actors includes current students and recent graduates of Concordia. The text is punctuated by images of fluttering papers and the sounds of handcuffs clinking, invoking sensorily the violent effects that the law has on racialized persons. Blackout resuscitates the voices of the uprising that echo across the void of time.

Driven by movement, Blackout intervenes in what we can know about the event and how we know it – the repository of knowledge known as the archive. It does so largely through movement. Choreographed by Diverlus, multidisciplinary artist and BLMTO co-founder, Blackout deploys vernacular gestures and repetition with stomping, clapping and chanting that blends pedestrian, Black resistance and Caribbean- inspired movement.

The archive is often concretized within buildings such as universities and museums as “absolute” and unchanging truth. In contrast, Diverlus’s choreography weakens their authority. The performers’ bodies, which conjure past students, are themselves archives in motion. They reanimate the university as a construction and subvert factual documents such as news reports and court transcripts as fictive. Moreover, the space taken up by their bodies racializes as white the spaces of education and the law that produce bodies of colour as riotous, while depoliticizing their rage. Writing in Canadian Theatre Review, Diverlus says that “BLMTO’s events are deliberate choreographic projects that incorporate visual, rhythmic, and tactical Black-centricity to challenge the belief that Black folks taking the streets are unruly and lawless, and to remind people of our humanity – and our collective history of well- coordinated mass resistance.” Through dance as protest onstage, Diverlus demystifies public protest and in doing so reveals how sophisticated it is.

Blackout gives a voice to the Concordia students of 1969, many of whom were of immigrant families promised security by Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau and who continue to be upstaged by white Canadian neo-liberalism. The computer labs are gone, but Black liberation persists.

Conclusion

Verba Ukrainian Dance Company, Chai Folk Ensemble, Signal Theatre and Tableau D’Hôte Theatre open up alternative portals of time and memory through which protest can be embodied effectively onstage. Dancers put their bodies on the line to step into the experiences of others so as to resuscitate the stories of those who have fallen and continue to fall on the pavement and in fields underneath trees, who are forcibly removed from their communities and who live in developing world conditions right here in Canada. Dramatic, unsettling and inconvenient in their truths, these four companies set up new models of performance creation that refuse and re-fuse dominant narratives governing colonial violence, systemic racism, conciliation and public memory. These works remind us that bodies are always already political.

CODA

April 23rd, 2019. At the Alton Gas site on the Sipekne’katik River in the Maritimes, students from India join Mi’kmaq water protectors – grandmothers who have occupied the site since 2017. In honour of Earth Day, their bodies unite to dance the bhangra. Coalescing with the river is a flood of solidarity and joy both ancient and new.

Learn more >>

Rodney Diverlus. “Black Lives Matter Toronto: Urgency as Choreographic Necessity” Canadian Theatre Review

Naila Ketela-Mae. “Black Lives Matter is Dramatic, Unsettling and Inconvenient. That’s the Point” The Globe and Mail

Jaana Parviainen. “Choreographing Resistances: Spatial- Kinaesethic Intelligence and Bodily Knowledge as Political Tools in Activist Work” Mobilities

The author would like to extend a sincere thank you to the artists for their time and candour.

~

Blackout Choreographer’s Notes

By Rodney Diverlus

What a time to be alive! The last few years have been electrifying for Black communities. From the emergence of a Canadian iteration of the Black Lives Matter movement, to Black-centric community organizing and an artistic renaissance, we are reshaping the Canadian political and artistic landscape. Half a century after the computer protests, the Black radical tradition continues.

Coming to this project, I was inspired by my experiences on the front lines of Black Lives Matter Toronto. While developing its choreographic score, I traced a lineage of resistance as far back as the slave ships of the Atlantic, to the sugar cane plantations of Hispaniola, to the fields of Africville. I leaned on the choreographies of Black political assembly and vocabulary derived of Black-led protest culture. Be it chanting, stomping, clapping, body percussions; from the pedantic to the vernacular, seeped in groove, pulses and polyrhythms.

Black-centric political action is deliberate about its use – and disruption – of space and the physical interventions made by Black bodies in that space. As such, I wanted to use these theatrical bodies in ways that responded to the imagined environment. I saw movement as an extension of the text itself; I didn’t want them to “dance” per se, but instead incorporate gestures, abstractions and at times mime as narrative symbols for a raging community.

From the performers’ natural movement instincts as palette emerged motifs that spoke both to the realism and the ethereal poetics invoked in the text. This included thwarting gestures like “Hands up, don’t shoot” and the Black power fist, finding new ways of physicalizing chants and developing abstract shapes individual to each player.

Immense gratitude to the creative team and the cast for their synergy throughout this process. Thank you to the six students who risked it all, for your defiance and unwavering commitment to justice.

I hope their story encourages you to reclaim your power. I hope you are moved to move; to use your bodies as their own sites of resistance; to clap, to chant, to stomp and to rage. I hope you are inspired to continue on our work of declaring and affirming that Black. Lives. Matter.