“Amelia” is one of the most anticipated dance productions of the season. After a much-ballyhoued European tour, and a stop in Ottawa at the National Arts Centre for the Canadian premiere, Édouard Lock’s La La La Human Steps opened the Festival Montréal En Lumière, the city’s mid-winter culturefest, this past Thursday. Lock was an honorary co-president (with American director Robert Wilson) for this year’s event, and the festival also contributed financially to the creation of the work, acting as co-producer along with seven others around the globe.

This sublime but ultimately troubling work features nine dancers (Andrea Boardman, Nancy Crowley, Mistaya Hemingway, Keir Knight, Chun Hong Li, Bernard Martin, Jason Shipley-Holmes, Billy Smith and Zofia Tujaka), with speed and, let’s call it, ‘extreme dancing’ as the focus throughout. The superb dancers’ furious rapidity and the velocity of the execution is truly awe-inspiring, and the dancing alone is to be commended for its astonishing accomplishment. Lock himself merits applause simply for the sheer audacity in getting these dancers to such an altered state of human performance. Lock often speaks in interviews about transforming the body and heightening the audience’s perceptions of what they’re seeing and experiencing in watching his work.

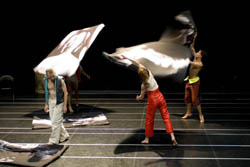

Pointe work aids him in achieving the fluidity he craves. In “Amelia”, not only are the women on pointe, but one of the male dancers (Smith) executes a beautiful pointe section with Tujaka. Witnessing this sensational cavalcade of gestures, in effect, creates an abstraction before our very eyes. On an essentially bare stage, the blur of the movement in the pirouettes and double tours en l’air, not to mention the whipping arms and hands, shifts our perception and we melt into the masterful, minute, fleeting interplay among the dancers.

Grey, black and white are the key tones of the piece. The four men are costumed in grey-black businessman suits with white or black shirts; the women wear similarly patterned slacks and jackets, and in other sections another set of chic tight-fitting outfits – black lycra tops and shorts (the women’s clothes are all by Vandal). Lock plays with either envelopping the body in pools of varying degrees of bright white light (by John Munro), or separating the dancing bodies from the audience by latticed scrims (decor by Stéphane Roy). The elegant metal filigreed screens rise and fall (sometimes with a clang), and provide a kind of shrouded intimacy for the dancers, enhancing the sensuality of the moment; they also act as a kind of casing, which frames the male/female duets. At times, the white lighting creates a bleaching effect, effectively rendering the dancing body increasingly transparent. More than ever, throughout the precise choreography Lock acutely develops the whole body with isolated accents in the tilt of the head, nuances of the arms and hands and inflections of the torso. Lock has worked to astonishing effect refining the torque in the body and the steady flow of movement. The resulting staged geometry of the dancing body is something Lock has never quite achieved in previous work. The bodies are not simply muscled bodies, capable of vaulting horizontally across the stage (in fact, he is working more on a vertical plane this time around), he is adding poise, grace and an incredible complexity to his equation, and in the process offering a new take on ballet.

David Lang’s score is splendid: a series of passionate studies for cello, violin and piano. The musicians perform live, and although they are generally located at the back of the stage, they do move around the entire stage space. Lou Reed provides the lyrics, with Alexandra Sweeton as the vocalist. Lock says he doesn’t concern himself with the relationship between the music and the dance, but there is a narrative that is imposed on this otherwise non-narrative work by the sheer force of the lyrics. A sampling from Reeds songs – “I’m as good as dead”, “Try to nullify your life”, “I am waiting for my man”, “You always have to wait”, “I’ll be your mirror’ – heighten the context of the partnering (and the twists in relationships) physically spinning out on stage.

As is Lock’s wont, film projections are interjected throughout the performance. A large, old-fashioned mirror-like screen descends to portray the projected images of the dancers, seemingly drawn from a computer-image system Lock has reportedly been exploring. It appears he is using something called “Lifesource technology”, which is designed as a full body, face and hand capture system intended to track and record the range of movement, expression and emotion of a human performer. Outlined, textured and shaded rendering are some of the selectable options in the program. “Flesh” is the name of another texturing tool in this creative envelope. Although “Lifesource technology” and “flesh” are not listed in the production credits, my conjecture is that the images on screen looked manipulated; each of the dancer’s features, the textures, mannerisms and calibration of their movements appeared computer-generated. The justaposition of live and computer-enhanced bodies encapsulates the difficulty posed by this work.

Apart from the sheer power expressed through the expertise and passionate attack of the dancers themselves, the central thesis of the piece seems to draw attention to the super-human efforts required of them, to the extreme physics of the body/machine. The overlay of the filmic imagery, which suggests an idealization of the bionic body – the mechanized body – in concert with live bodies pushed to their concrete physical limits, injects an icy pall on the production. In talking about his work, Lock refers to perceptual “free games” – superimposing representations of the dancers and the dancers themselves – and how this interplay can be used to get people to pay real attention to what they are seeing. He is apparently convinced that by showing the human body in an extreme way he can provoke a deeper and more alert way of seeing in his viewers.

Ambitious, enlightened metaphysics maybe, but he loses his audience almost as quickly as he get them. Lock’s choreographic intent – the speed factor, for instance – is generally understood quickly. But while the company was applauded with a great ovation at the end of the performance, many in the audience fidgeted and seem bored at times during the work. The repetition of the movements in the various sections of this challenging piece and the continued re-entry of the filmic images, if the crowd’s body postures throughout the performance were any indication, seemed to lull the audience further into an indifferent state.

Tagged: Ballet, Contemporary, Performance, Montréal , QC