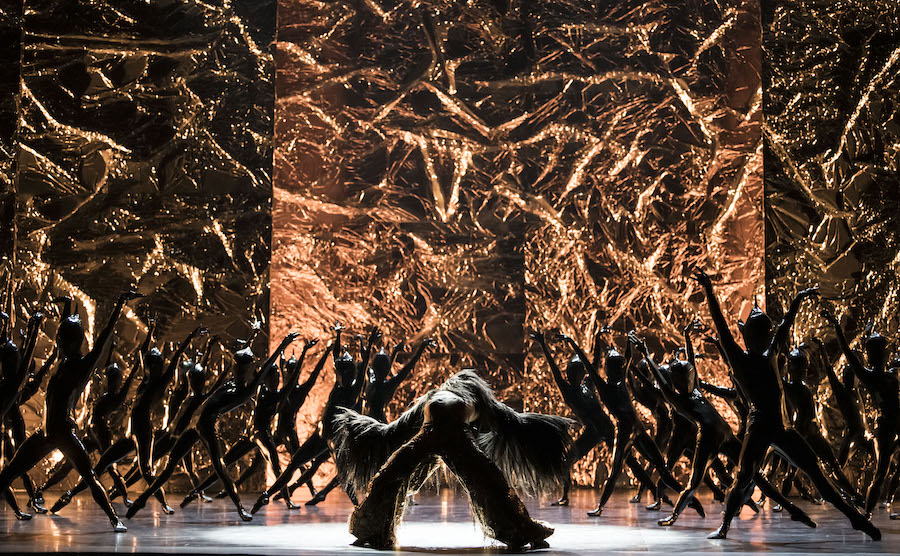

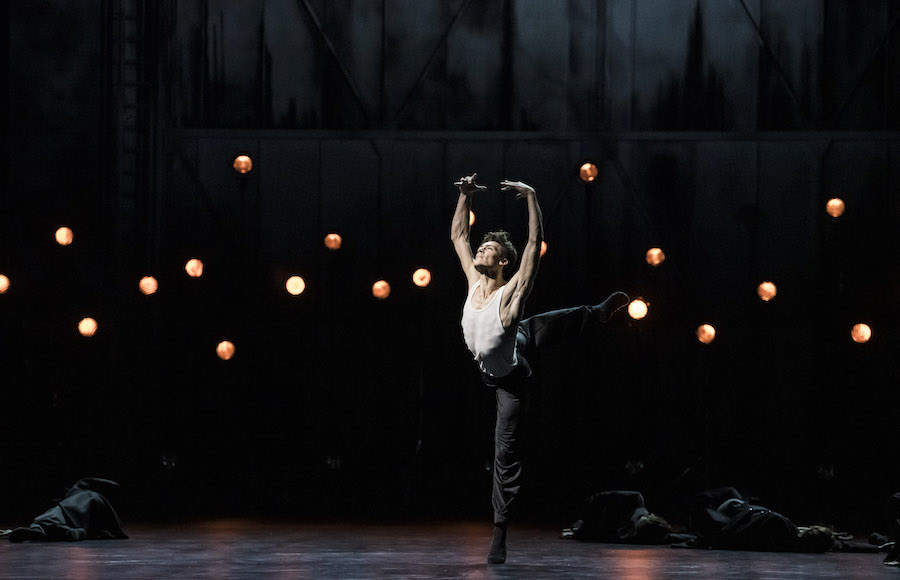

Starting Wednesday, audiences in Canada will get an exclusive chance to see Crystal Pite’s Body and Soul — originally created for the Paris Opera Ballet in 2019. The work will be presented online through Digidance, a collaboration between the National Arts Centre, DanceHouse, Harbourfront Centre and Danse Danse.

Pite, originally from British Columbia, has become an international name choreographing for companies including Ballet BC, The National Ballet of Canada, Nederlands Dans Theater I and Paris Opera Ballet. In 2002, she founded her own company, Kidd Pivot, in Vancouver. Her work has won several awards, and in November 2020 she was named a member of the Order of Canada, one of the country’s highest honours.

Body and Soul is her second work for the Paris Opera Ballet — she created The Seasons’ Canon in 2016 — and what will stream Feb. 17 through 23 is a filmed run of the original 2019 production.

The Dance Current spoke with Pite about Body and Soul, watching dance meant for the stage on a screen and the “slight sense of terror” that comes with choreographing.

***

Grace Wells-Smith: How do you think [Body and Soul] is going to be for the audience watching it onscreen versus onstage?

Crystal Pite: Yeah, I’ve been thinking about that. It’s a funny one because I think when you try to translate a live performance from a stage to the screen, you inevitably lose some pretty important things, don’t you? You lose the risk that is inherent in a live performance. There’s an aliveness that I think that we feel as performers and as audience members when something is at risk. When you’re experiencing a live event, with your fellow audience members, there’s a kind of energy and there’s a palpable feeling in the air that something is alive and vital, and you’re participating in it. You feel complicit in making it happen in the moment, I think. When you’re watching it on a screen, a lot of that gets lost. The stakes aren’t as high. There’s not the element of risk. This thing has happened in the past, and you’re watching a replica or a document of it. And everything is sort of safer in a way.

There are a couple of things, seeing something onscreen, that kind of compensate for that. And that is, of course, the proximity that you have, the ability to look at a work from several different angles rather than just the one seat that you’re normally in in the theatre — you can see this now from above, you can see it from up close, you can see it from an angle, you can get right inside it almost. … So you know, I’m a theatre artist, I love the live experience. And that’s why I do what I do, to be in there in that sacred space of the theatre with other people. But on the other hand, I do appreciate being able to bring this work home and to be able to share it with my fellow Canadians and even just to have access to it myself. It’s satisfying.

GWS: Right.

CP: Yeah, it is nice, you know. We make these things, we make these ephemeral things, and then we leave. I left Paris and went home with nothing in my hands, nothing. “Bye!” [laughs] And “Thank you!” and go home with nothing. So it is nice to have a record of my experience there and to have a version of the work that keeps it alive for me in another way.

GWS: In the Digidance press release, you mentioned that Body and Soul was a significant part of your creative life. How so?

CP: Well, I think just working in the Paris Opera House, for starters, is significant for me, just being inside that space, being surrounded by all that history and all those stories. And just becoming part of the legacy of that institution is just such an honour. And there’s a weight to it too that I was trying to hold myself up underneath. I love the dancers. It was my second time creating there; I made a piece for them in 2016, called The Seasons’ Canon. And so it was really lovely to return to a lot of the same dancers and to be able to build on the things that we’d discovered together during Seasons’ Canon creation and to be able to take them further. They were also, as dancers, just more skilled, more masterful, more available, more complex than they had been three years prior. So that was also so exciting, to see their growth and how quickly they had learned and assimilated new things. And that speaks to the other choreographers that they’ve worked with and the work of Aurélie Dupont, their director, and bringing new contemporary work to her company and giving the dancers an opportunity to add new dimensions to their dancing. So I reap the benefit of all the other creators that they’ve worked with, and I can really see that growth in them.

GWS: I’m wondering if you can tell me if you’ve noticed any differences between working in Paris versus working here in Canada.

CP: You know, I think a ballet company in and of itself is its own kind of culture and its own kind of world, isn’t it? It carries with it all kinds of complexity and possibilities and limitations. So I feel like when I enter the world of a ballet company, I step into something that’s both familiar and kind of confounding. So I guess I see more similarities than differences across ballet companies. They’re just giant institutions. The Paris Opera has 154 dancers, I think. So imagine 154 dancers in a company and trying to get to know them, trying to locate the people you want to work with. It’s pretty intense.

Differences between working in Paris and in Canada? I don’t know. I mean, I guess we could talk about budgets and production values and possibilities of stage time and the kinds of things that are possible in a house like the Paris Opera that maybe wouldn’t be possible here in Canada, just because of a budget. I mean, that alone, there’s a bit of a different scale at work there. I don’t know the numbers, but you can sense it, you can feel it. The more generous stage time alone is a huge factor in how I can think about creating a work if I know I’ve got, let’s say, 16 hours of tech time, as opposed to five days. It changes everything about what I’m able to even hope to do. And if I factor that in early in the process, it affects everything, all the decisions I make artistically, knowing if I’m going to be able to achieve things, technically speaking.

GWS: Right. That makes me think of Angels’ Atlas. I went to see that work, and I know that you made that work really quickly. And so I imagine that’s quite different than having, you know, five days of tech time.

CP: Yeah, actually, that’s a great example because the programming and the creation process of working with the backdrop, the reflective light work that Jay Taylor and Tom Visser created together — that’s enormously labour-intensive. And we did a lot of that work here in Vancouver, and the National Ballet rented theatre space here in Vancouver, and we gathered here. This is probably not important for your article, but it’s just kind of an interesting tactic that we play because we knew we wouldn’t have enough time on the stage at the Four Seasons. Like, we just can’t get enough time, not enough hours in to do what we wanted to do. So we did a lot of the experimenting and the process here — in a small theatre here in Vancouver — and we didn’t necessarily do the actual programming, but we found out what the ingredients were and how they might work together so that when we did hit the stage at the Four Seasons, we could move really, really quickly.

And the same thing, I have to say, is that the same thing is exactly true of the dancing. So I built a lot of the choreography here on the students that I work with at Arts Umbrella. There’s a beautiful program here of young dancers that I work with, and I built a lot of the choreography on the students before I went to Toronto so that I could do the experimenting I needed to do that’s time-consuming and labour-intensive with students and then have it kind of like prêt à porter; I could just kind of take it to the National [Ballet] and deliver some of those themes directly.

GWS: Those students must have loved it.

CP: Well, you know, I’ve worked with the students on Angels’ Atlas. I also worked with them in a similar way for Body and Soul and for The Seasons’ Canon and for Flight Pattern, which is a big piece I made at the Royal Ballet. So I’ve done at least four, if not more, processes using the students as a kind of amazing giant human sketchpad. And with the students, I’m able to take my time and I’m able to investigate things I don’t have the courage or the time to do in those pressurized, big company situations. My actual time in the studio with the dancers in Toronto and on the stage is only a part of the story. I do a lot of prep here in Vancouver before, and the same is true in Paris.

GWS: Your work also sometimes includes text, and I’m specifically thinking about Revisor. And so I’m wondering how that use of text and theatrical moments affect choreographic work?

CP: Yeah, I’ve always loved working with text in a variety of ways in my work, and I find it very inspiring. And I really enjoy — certainly with Revisor and Betroffenheit, The Statement. Those are all projects that I’ve worked on with Jonathon Young. Working from a script and having the text as a kind of guide and as a structure, it’s really satisfying. And it also allows me to get a content that is more complex and be able to deliver more complexity and more narrative, actually, in this work. So Body and Soul, I did also use a scrap of text. And it was a little scrap of text that Jonathon and I used early on in our process of making Revisor. Revisor premiered in early 2019, and Body and Soul premiered in the fall. So they’re kind of, in a weird funny way, they’re a little bit linked. The link is this little scrap of text. And it was just a scene that describes two figures in a kind of conflict. And it’s done in a kind of stage-direction style. So it describes the conflict of two figures. So the text is something like, ‘Overhead lights snap on to reveal two figures in a small interior. One figure lies on the floor, the other paces back and forth. Left, right, left, right, left, the hands move incessantly touching chin, forehead, mouth, neck…’ It sort of goes on and describes mechanically what’s happening. And the text, it’s very, very simple. And it’s this physical, mechanical language, but it describes this conflict. And what I was interested in doing with Body and Soul was trying to use that text and let the meaning of the text morph and change with each iteration. So sometimes you would see the text delivered by two individuals. And then at another time, it’s a group and an individual, and then two groups of people, and then it even moved into something like these swarm creatures that arrived at the end of the production, where it moves into, like, it’s not even human anymore, but the text still stands, it’s still conflict between figure one, which is now an entire swarm of creatures, and figure two, which is another swarm of creatures. [laughs] So I was interested in what conflict looks like, what this particular described conflict looks like in all these iterations and how the meaning could change.

GWS: And so with text in mind, are you reading anything these days?

CP: Yeah, I’m always reading lots of different things at the same time, but I’m not reading anything right now that I’m looking to choreograph to, if that’s what you mean. I just try to fill up on all kinds of different things to inspire me. But I do love to write, and in fact, I have started writing recently some texts that may turn into choreography. So I do like using text as a starting-off point. And I find I draw a lot of inspiration from it. And I draw a lot of inspiration from people that work with texts in their work, just because it’s such a different brain and I want to know more about it.

GWS: So have you been watching a lot of dance performances during the pandemic?

CP: I have not. I haven’t actually. I’ve watched — there’s a few things, but I find it very hard to be on the screen. I find it exhausting. And I’ve also just been wanting to take some time away from all things theatre and all things dance for a bit. I had planned 2020 as a sabbatical year. I had put that into motion about five years ago. I kind of looked ahead in the calendar, and I saw that the premiere of Angels’ Atlas in Toronto was February the 29, and I took that as my end point. And I said, from there, I’m going to take a year and not choreograph and not create anything. So that had been a plan for a while. So it dovetailed quite nicely with the pandemic. So I feel very fortunate that I wasn’t in the middle of a project or wasn’t chasing a creation, and I wasn’t in mid-stride with something creative because I think that would have been really, really hard. And I really feel for my colleagues that were just on the cusp of something and had to, like, shut it down. My company was on tour. We were in the middle of a tour of Revisor, or at the beginning, actually, of a tour of Revisor, when the pandemic hit, and we had to send everybody home. And that was tough to sort of cut that momentum. But in terms of me creatively, I haven’t really been very hard hit in terms of creation. I had a lot of remounts that were postponed or cancelled, and some facilitating to do on other people’s projects, but nothing of my own that was cut short. Lucky.

GWS: Yeah, that is lucky.

CP: Yeah, and so now I’m just at this point now starting to emerge and think about what I’d like to make next and how to think about creating now. Still wondering all that. What about you? Have you seen a lot of dance online while you’ve been home?

GWS: Well, you know, as the editor of a dance magazine, I’m just kind of always watching and seeing and everything. I hear what you mean, though. If I’m honest, a lot of times before I’ll be like, ‘I don’t want to open up my laptop again.’

CP: Yeah. Yes.

GWS: And it’s a bit — you know, I find it a little bit sad too just because of the things that you mentioned earlier about what we’ve lost and everything. But on the flip side, I’m seeing a lot more people making dances to be specifically filmed. And so it’s kind of nice seeing people branch out like that and adapting, so I think some of the sadness is starting to go away. And it’s not as exciting; you don’t get dressed up, you don’t go out for dinner before. So, like, half the experience, I feel, like, disappears.

CP: You’re right, there’s a whole surrounding experience that gets lost, right? I went to see a really interesting concert. Music on Main was putting on these kind of one-to-one concerts where it would be a single audience member and a single musician playing a piece. And it was a beautiful experience to go and listen to this concert that was played for me alone. But I realized, I felt so — even though I was with this musician, I felt the desire to share my experience with someone beside me, you know? I felt like the responsibility of being the only audience member was almost too much to bear. Like, I felt like I couldn’t be attentive enough as the sole audience member. I needed to be able to share it or share that weight or that responsibility with a group of people. I never could have imagined that that’s how I would feel until I was actually in there.

GWS: That’s a really unique idea, I must say.

CP: Uh-huh. Yeah, it was fascinating. I loved it. It was kind of confronting and beautiful all at once.

GWS: And so my last question for you is this is only the third time that the Paris Opera Ballet is going to be performing ‘for Canada,’ I’ll say, since they’re not going to be in Canada — how does it feel that it’s your work specifically that we’re going to be seeing?

CP: Well, I always feel nervous when people look at something that I’ve made. I just do. [laughs] It doesn’t matter what it is or who’s doing it. I always feel a slight sense of terror of being judged or the work not connecting the way that I hope it would. So yes, I feel a kind of nervousness, but it’s also thrilling to think of being able to share this work with the folks at home, so to speak, you know. I go off and I do these projects, and like I said earlier, I come home with nothing. So it is nice to feel like I can share that with people here and hopefully get some feedback and just, yeah, feel the resonance of it again, in this format, such as it is. But I guess what I hope is that people just recognize how extraordinary those dancers are, and to have a chance to connect to that alone is exciting.

This conversation has been edited for clarity.

Tagged: Contemporary, All