Picture yourself in a situation where you are learning a language you aren’t familiar with. You’re in France, for example. You ask your francophone friend how to order a coffee from the barista. You go up to the counter and say: “Puis-je utiliser vôtre salle de bain?” and find yourself being guided towards the bathroom, coffee-less and confused.

The learning process that occurs when beginning to study something new can be categorized into what I think of as an arc of five stages: initial response, awkwardness, mimicry, understanding and appreciation. Now if you apply this arc to the example of learning French, you can relate to the truth within these so-called stages. When you hear a conversation in another language, it’s overwhelming. You might think: “How on earth will I ever be able to understand this, let alone actually speak it!?” Yet you’re a resilient trooper and carry on, which leads to the awkwardness. So many mistakes: bad accent, wrong verb tense, long uncomfortable silence while you mentally translate the next word you want to use. Still, all of this isn’t enough to crush your willpower. You prevail, no longer cryptically pairing random words together and desperately hoping your listener can somehow understand you while you try to make sense of this new language. You’re in the mimicking stage now, blending in with smooth sentences projected with an acceptable accent, yet you feel like you’re babbling gibberish. While others may understand, these words are still only sounds to you. But, with practice and patience it soon becomes an enjoyable second nature.

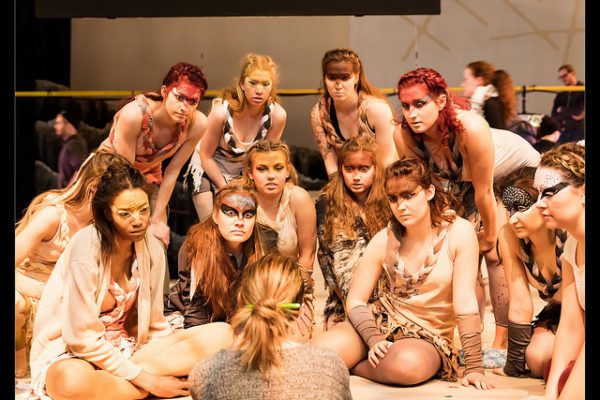

If you think of dance as a language, then this breakdown of the learning process can be recognized in all forms of dance. As a graduating student of the School of Toronto Dance Theatre, I have had the opportunity to experience and witness the progression of Graham-specific learning over the course of three years. Martha Graham was one of the founding pioneers in modern dance, inspired by politically and socially charged subjects. Her infatuation with the evocative potential of the human body and her creativity had a remarkable influence across art genres beyond dance. The root of her technique derives from the natural physical bodily reactions to emotions, refined into movements initiated from contraction, release and spiral.

Since Graham is a challenging technique requiring a deep muscular and visceral understanding, it is geared towards mature students. Many students entering first year have little or no experience with it. It seems as though the majority of beginners undergo the same adventure, asking critical questions in order to get a grip on what this technique really is: What is a contraction? Why do I have it some days and not others? Does a “proper contraction” even exist or is everyone who believes in Graham a part of some strange cult? Why is a cupped hand even a thing? Pardon me… did you say a “pretzel”? You want me to sit down, cross my legs, balance on one hip, twist to the side and fold my body in half all at once? Ok, sure – why not?

But by third year you begin to embody the tension, relaxation and coiling movements within this form. Harnessing power from the energy flow of these actions becomes so satisfying that relating to the physicality on an emotional level begins to happens naturally. Students even stop looking at the cupped hand as simply an odd position and appreciate how a it mimics the forms within the rest of the body.

When asked what kind of growth she’s noticed over the years from first to third year students, Wendy Chiles, a School of Toronto Dance Theatre Graham teacher shared these words of wisdom:

“For the most part first year is a year that embraces the enthusiasm of getting into a program and working in class with others who want and believe in shared goals. Yes, there may be some who can get overwhelmed but for the most part I find most are inspired to be doing and learning more about their bodies, dance and the demands that dance training requires. Fatigue, learning to take care of oneself, managing time and making new friends can be daunting for some.

However, I find that more issues present themselves in second year. Injuries, doubt, pain and demands take over for some. There can be many more absences. I think that some label Graham as being too hard; however, it is a technique that fully embraces the training and awareness of the body. Because it is so specific, one learns how to move safely, clearly, eloquently and, to quote MG, one becomes an ‘Athlete of the Gods’. Mimicry is an essential part of training, it is not only in Graham, but ballet and an element of choreography. A dancer must learn to do the movements that are being taught.

As one moves to third year, the understanding of artistry is stronger, skill development is much stronger and the student is understanding commitment and focus. Being in command of oneself and the dance material … is easier and more accessible.”

In the end, it doesn’t matter whether you are learning French or a new dance technique, it is surely going to be a process. It will likely begin with some undesirable feelings of doubt and discomfort but by the time you reach the other side of the arc, you come out on top: capable, skillful and ready for more. I hope by reading this article you’ve been inspired to look at the ‘pretzel’ of whatever you are trying to learn, right in the eye, and say with confidence: “I will conquer you.”