Editor’s Note: Digidance, in collaboration with the Fondation Jean-Pierre Perreault, presents Perreault’s JOE online March 17 through 23. The work was originally created in 1984, and the filmed version that audiences will see this week was produced in 1995 by Radio-Canada. The below article, written by Bonnie Kim, was originally published in the May 2004 issue of The Dance Current. This version has been copy edited to reflect our current style.

***

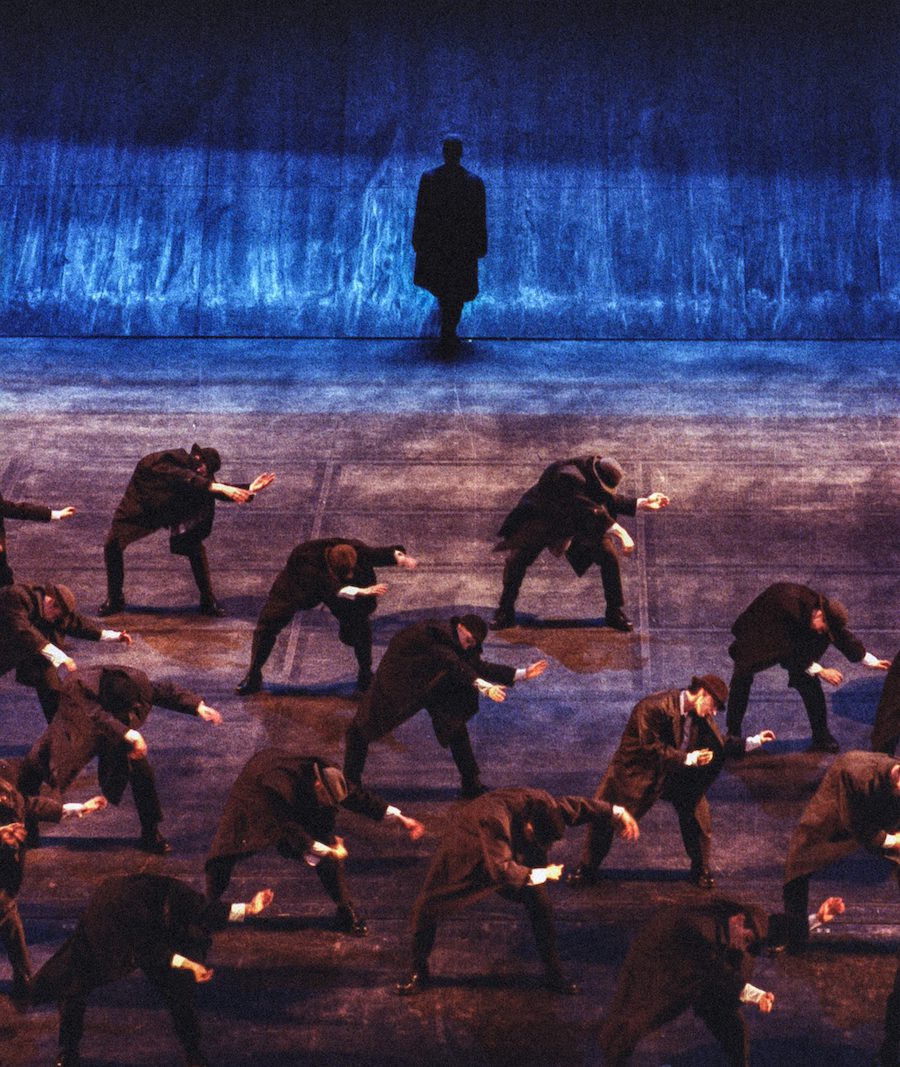

They’re throwing themselves against the ramp with such brain-rattling force that my body clenches with each impact. After sliding and tumbling and somehow or other getting down to the floor, they’re up on their boot-clad feet, charging towards me. I push my chair back against the wall to try to get out of their way when suddenly, as if caught by wire fencing, they stop on a dime and drop to the floor — 30 panting, curled-up balls.

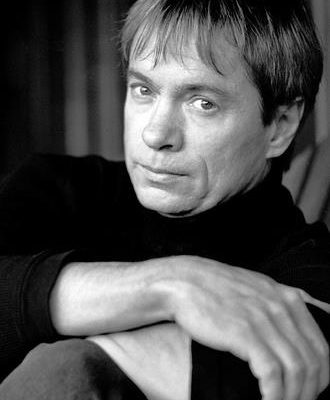

My first encounter with JOE, Jean-Pierre Perreault’s signature choreographic work, was in 1989 watching a rehearsal for his company’s performance at Montreal’s Place des Arts. Originally choreographed in 1983 on dance students at the Université du Québec à Montréal, this performance of JOE was only the second with a cast of professional dancers, the first being in 1984. At age 21, I had never seen anything like this piece. It was fervent and epic and so utterly moving in its simplicity that I wanted to be one of those breathless bodies scattered across the floor. Five years later it happened; I became a JOE.

In the spring of 1994, three companies — Fondation Jean-Pierre Perreault, Dancemakers and Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dancers (WCD) — joined forces for JOE’s 10th anniversary and first Canadian tour. With 32 dancers, it was the largest cast of JOE yet. I was then a member of WCD, and we incorporated JOE training sessions into our regular rehearsal days. Artistic Director Tom Stroud, a former pro JOE who was also dancing in this co-production, led us through a daily series of combinations from the piece so that we could build our stamina and become familiar with Perreault’s vocabulary. I was so freaked out about being in peak condition that I even quit smoking. But all of that preparation seemed futile the day I met the ramp.

I’m standing at the bottom of the steep, black slope. From this vantage point, it looks far more ominous than from the front of the studio, about 35 feet away. I’ve got my uniform on — black socks, steel-toed army boots, trousers, shirt, tie, suspenders, jacket, overcoat, hat — and my heart is racing. I figure it’s now or never, so I take a deep breath and run up the ramp. A little shaky, a balance thing really, but not bad. I get to the top and stop. Leaning forward seems to steady my body. Hmm, I think I’m getting the hang of this. Might as well go back down. On my first step back, I know I’m in trouble. I can feel my body tilting backwards ahead of my feet, so I attempt to run faster to compensate, but that only seems to generate more speed and before I know it the ramp whips out from underneath me and I land smack on my poorly padded behind. Brain-rattling.

It was obvious from the start that this JOE experience would be unforgettable. There was an acute awareness that something remarkable was going to occur when these 32 dancers — some of the most extraordinary in Canada — and Perreault himself, finally converged in one studio. On the first day of rehearsals, we were each assigned our costume, which we wore for every rehearsal from that point on. Perreault had to OK every single JOE, often trying a different hat or tie until a unique personage emerged. We also had to shave the base of our hairline, the part where the bottom of the hat sits, so that we’d all look somewhat uniform from behind. In the end, each of us was particular and yet one and the same. Because much of the piece is danced with heads down or facing someone’s back, we learned to recognize each JOE by his or her specific coat, hat, pant cuffs or movement quality. It’s amazing how much personality is revealed in a couple of shuffles. At some point during the process, I realized that I had never looked in a mirror and seen myself in full JOE gear. I decided that made sense. Not seeing my JOE self helped me to feel anonymous, humble even. It was easier to blend in — to be just another JOE, I suppose.

We’re lying on the floor, waiting, listening. It’s the fainting section (la cloche suivie des évanouissements). Daniel Soulières taps his boot eight times, we scramble to our feet, shove hands into pockets, look up and wait, and listen. One lone JOE begins stomping, then another and another until all 32 of us are stomping in glorious, rhythmic unison. We’re creating music — thunderous, harmonic music I can actually feel in my bones.

I’ve conquered the ramp! Feeling rather confident, I voluntarily place myself in the first row for the waves (la vague), not fully realizing what I’ve just committed to. Turns out there are three rows of JOEs that will run up and down the ramp a number of times. Without hesitation (which, by the way, was a favourite directive of Jean-Pierre’s), some of the older or slightly injured dancers take a spot in the third row, a.k.a. the “old” or “injured” row, because they’ll have to run the least. The first row, known affectionately as the “young” or “keen” row, will have to run up and down about 16 times. I’m concerned.

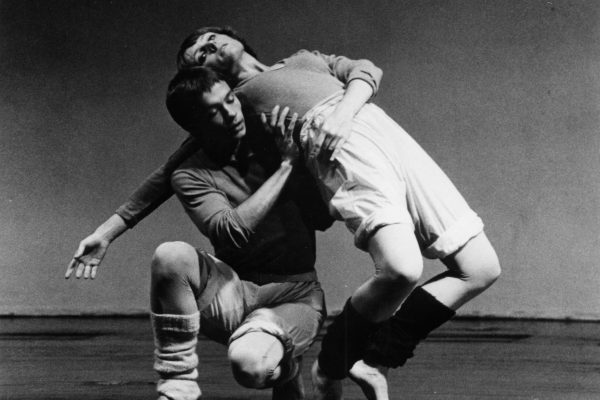

Each day was draining, not merely for its physical demands but for the constant attempt to reach and maintain such an impressive level of excellence. I think most of the dancers, regardless of experience, felt intimidated by Perreault because his presence was awesome. His work was awesome. There was a distinct shift in energy when he entered the studio. When I say that every day felt like an audition, you might begin to understand the kind of heightened environment that was JOE — we wanted to do well, we wanted to be worthy and, oh my God, we didn’t want to screw up. Ultimately, we were all responsible for driving the piece. With 32 dancers performing for 70 minutes without music, the amount of focus and concentration it took to maintain counts and rhythms was beyond challenging. It was this shared accountability that was the heart of JOE. Despite the range of experience, all of the dancers were on the same playing field. I distinctly remember during one punishing section of pounding jumps, Soulières and I would grab each other’s hands and squeeze tightly as if to say, “Hang in there, we’re going to get through this together.”

Considering the intriguing assortment of characters and temperaments, it’s amazing that we all got on so well. The camaraderie both in and out of the studio was incredible. And it made absolute sense when a friendly wager amongst the 32 dancers revealed that the average JOE age was, in fact, 32. The JOE social life was a crazy, hazy, epic tale, and I have the photos (and negatives) to prove it.

At the time, I don’t think there had ever been a perfect performance of JOE, meaning that somehow, somewhere, something had gone wrong. Though perfection was never our primary goal, with the complexity of the work it’s not surprising how easily the unexpected could and did occur. On opening night in Quebec City, for instance, after weeks of being a ramp dominatrix, I fell on my butt during la vague. Talk about feeling humble.

It’s around 10 p.m. June 16, 1994. The lights are coming down on our final show at Ottawa’s National Arts Centre during the Canada Dance Festival. I am standing on the ramp close to the floor and, as the lights come back up, we all turn to face the audience and run downstage to form a line. The bow, like the piece, is a finely tuned choreographed sequence, which involves running offstage, then up and down the ramp, back into the line and then reversing the whole thing. The packed house of more than 2,000 is on its feet cheering “Bravo!” for the entire length of our bow. In fact, we have to repeat the pattern a few times because they just won’t stop. I am exhausted. We are all exhausted. But this reception, this overwhelming rush of appreciation — for the work, for Jean-Pierre, for our efforts — is so remarkable, so special, that I tell myself to savour it.

Because I knew at that moment what I still know now, 10 years later: I will never experience anything quite like JOE again.

Tagged: Contemporary, Writers & Readers, All