This article was originally published in the Fall 2022 print issue.

The swelter of summer heat leaves a glow on the skin. As we sit in her airy kitchen, at a vintage round wooden table, Linda Rabin serves two glasses of cool water to quench our thirst. The kitchen in her third-floor flat in Montreal’s Mile End district, where she’s lived for 41 years, leads to a narrow back balcony overlooking an enclosed courtyard. It’s a longtime immigrant neighbourhood, changing with time, but where she feels very much part of the fabric of the “hood,” as she calls it.

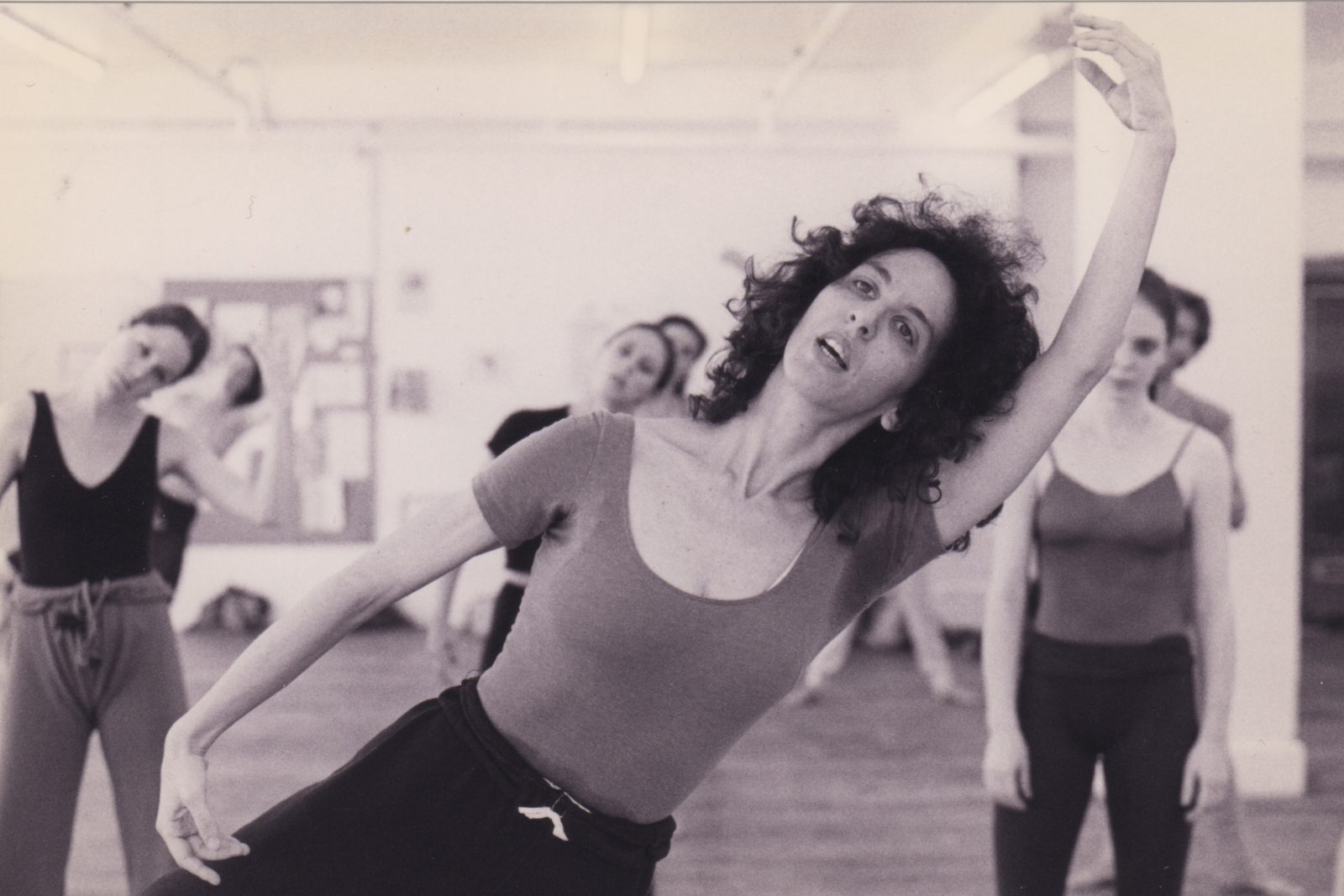

In the early 1980s, I took her modern dance classes at Linda Rabin Danse Moderne. She was authoritative and precise, with keen eyes and voluminous, curly dark hair. Today, her still full head of hair, now greyer, frames her same broad smile. Quite like old times.

Rabin’s calm and responsive as she recalls an early awakening. “I remember as a young kid, I was lying in my bed and I saw what seemed like a meteorite in the space up towards the ceiling. It was both coming towards me and away from me. There was a sense of ‘almost’ that I could connect, but not quite. I have no idea what it means, but perhaps when I die, I will know.” It’s a plainspoken statement of practical mystery. The memory grounds her, sparks emotion and is fundamental to understanding Rabin’s gifts as a seeker.

Rabin’s extraordinary skill has been to shift conceptions of dance and movement in Canada. Throughout her prolific career, she’s assumed many roles as a teacher of dance – notably co-founding the school that would become École de danse contemporaine de Montréal – a choreographer, a rehearsal director, a somatics practitioner, a mentor, and a Continuum teacher. Her depth of questioning and deep listening have resonated across generations of students, and the Canadian dance scene is better for it.

Rabin’s quest as a youngster to today is deeply linked to her innate curiosity, cultivated in her early Hebrew education. Born and bred in Montreal, she attended the United Talmud Torahs of Montreal day school, a parochial system where she was educated in four languages. “Whenever we studied the chumash – the bible – whatever we were reading, there was a deeper meaning. You cannot take it as a story. It represents something. So whatever I see or look at, I feel that it symbolizes something that I will understand at some point,” she says, when the meaning emerges at the right time. “I’ve carried that through my life. In my teaching, at whatever phase, from early on as a technique teacher to now, I’m looking at the person in front of me for what’s lying beneath what’s evident. That’s been my pursuit.”

Carol Prieur, a dance artist and longtime student, calls Rabin transformative. “She’s searching constantly, and I’m drawn to that,” she says. Rabin’s vibrant nature, her humour, playfulness and perspective are a big part of her draw, and her extraordinary teaching skills are unsurpassed. Lin Snelling, a dancer who teaches, writes and performs, characterizes Rabin, in her teaching capacity, as “insightful, combining her own accrued wisdom with her understanding of the potential of each student on their own, and also together in the room.”

She is 76. Her artistic imagination coalesces a sense of the spiritual transcendence with an engaging curiosity that engages movement as life. She seems to have always been moving and dancing. And she’s not letting up. Movement is what connects her to the world. With recent accolades like the Lifetime Artistic Achievement Award, presented by the Governor General’s Performing Arts Awards, and being named a member of the Order of Canada, her legacy is still growing.

***

At five years-old, Rabin took ballet and tap at a neighbourhood dance school. After-school ballet classes at the Talmud Torahs, taught by Tatiana Kushinsky, further fueled her passion. As a teen, she was enthralled by the television program Your Hit Parade where the highlight would be a dance choreographed to the number one song of the week. “I thought, That’s what I want to do. I want to be a choreographer,” she says.

In 1960, when Rabin was about 13, a classmate at Mary Beetle’s Dance School told her about Elsie Salomons’ creative dance classes. She loved what her classmate was describing so told her mother she wanted to join. She then called Salomons and indicated that she wanted to be a choreographer.

“Well, before you can be a choreographer, I think you need to learn to dance,” said Salomons, then asking a young Rabin why she wanted to do this.

“Well, I want to feel like I can dance whatever I want to be,” said Rabin, seeing an apple on the table. “If I had to dance the apple, I could dance an apple. That’s what I want to do!”

At 14, she arrived at Salomons’ studio, which offered an eclectic mix of folk dance, modern dance, ballet, improvisation and creative dance. In her first class, the students wore black leotards and tights cut off at the feet, and they all improvised around a shy, non-moving, Rabin.

Salomons picked up on Rabin’s self-consciousness, and when the improv was over, she encouraged her to move to the other side of the room. “We went off and improvised again. I was surrounded by a couple of people who were so involved in the improv, and I felt it so strongly. I was being taken by the energy around me. I had no choice, so I started to improvise. I remember it so clearly… I was in prison, behind bars, and I had handcuffs. I was chained at my wrists, and I started to move, and the whole thing was about freeing myself from the handcuffs and the bars and opening into the light. From that moment on I was home free.” To this day, Rabin credits Salomons’ encouragement and smarts for opening up the doors to that internal creativity, allowing her to express emotions through movement, and instilling confidence that nobody could take away.

When she was 18, this encouragement landed Rabin at New York’s Juilliard School in the mid-1960s. She immersed herself in José Limón’s musicality and fluidity, the intensity and power of the spiral in Martha Graham’s technique, as well as Anna Sokolow’s composition classes. The latter’s approach to teaching choreography was to say, “Don’t borrow. Steal.” That don’t-hold-back approach would resonate for Rabin. “The way that I think today was already prevalent then. I didn’t have the kind of language I have now, but my spiritual search was looking for the essence. What does it mean to be dancing, not just dancing the culture, but getting inside, at something more universal?” she says.

After graduating in 1967 with a bachelor of fine arts in dance, she travelled, discovering other cultures and ways of life. She settled for five years in Israel, working with the Batsheva Dance Company from 1971 to 1973 as rehearsal assistant and company teacher for then-director and fellow Canadian Brian Macdonald. It’s where she started her life as a choreographer. While in Israel, an encounter with Rika Cohen, an Alexander technique teacher, liberated her. “The knots in my brain untied,” she says. She had a new understanding of her body and her sense of space shifted. She ultimately saw movement differently and became interested in slowness. “How could we do the least on the outside, to experience the most of what’s going on inside?” she asked. Later, she moved to England for a year, working as rehearsal director for the Ballet Rambert, before returning to Montreal.

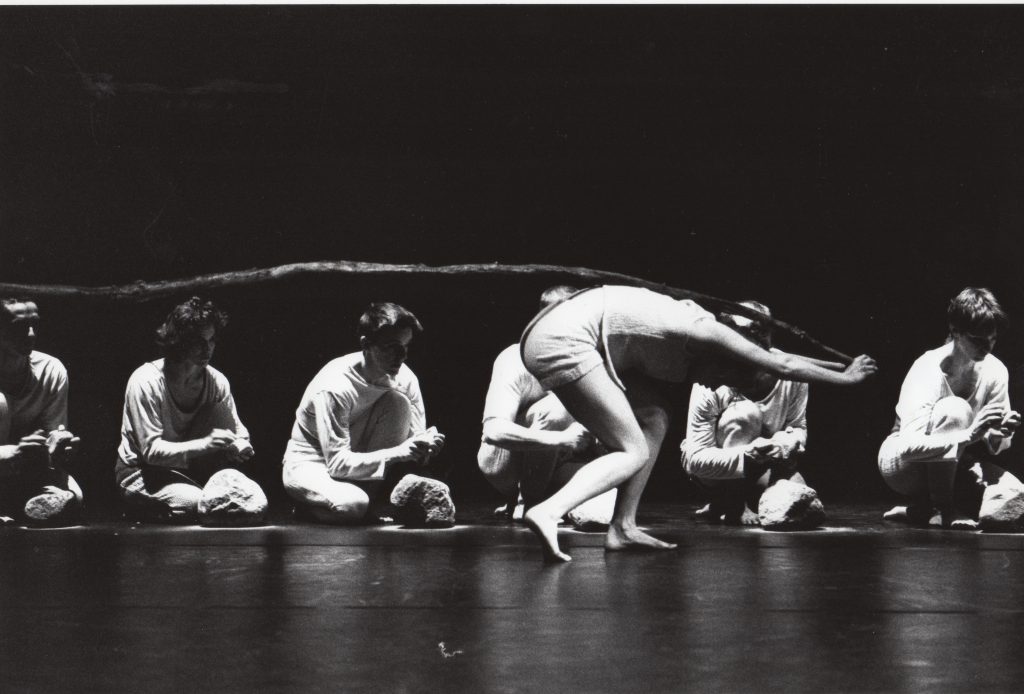

The need to keep moving had her teaching and conducting workshops in cities across Canada. Then, in 1979, she went to Japan for a year on a Canada Council for the Arts grant, spending time researching and nurturing her interest in dance theatre. She took classes in Noh theatre, particularly observing Kabuki dance-drama, and learning the traditional dances of folk origin, and also shamanic dances. “At that time, I was driven to look for what is the essential, the ideal core, so that when I find it, I could seize it and that’s what I would share. I was always looking for the truth, the ‘one’,” she says. “What I discovered while I was in Japan was that there was no ‘one’.” Further, what she witnessed in those studios was a tremendous bond between teacher and student. “The devotion, commitment and respect made me realize that if I wanted to really transmit information as a teacher, I could not continue to travel around, left, right and centre. If I really wanted to make a difference, I needed to stay put in one place and offer something that was going to be long-term.”

While in Japan, Rabin wrote to the late Candace Loubert, with whom she had a strong affinity artistically, asking her about opening a school together. They had worked together several times at Les Grands Ballets Canadiens and then in Rabin’s production The White Goddess. Back in Montreal, she and Loubert got together, and started Linda Rabin Danse Moderne. Located in The Belgo Building, a former rag trade building, on the corner of Bleury and Ste-Catherine in the downtown core, the school officially opened in January 1981, but without studio space. It was the following May they got their studio: a fabulous space, with some 1,800 square feet, floor-to-ceiling windows on two sides, and a good wooden floor. “With one pillar, only one!” Rabin laughs. The school grew in popularity, as artists thrilled to the explosion of dance in Montreal. Rabin credits herself with being in the right place at the right time to be a part of this burgeoning wave of creation and invention.

Her modern dance technique classes were augmented by Richard Pochinko’s pioneering clown and mask practices, alongside Ann Skinner’s sound and voice coaching. “[Pochinko’s] process of going for authenticity, the essence of the individual, and the essence of a text, really inspired me to search for that kind of authenticity in dance,” says Rabin. Russian ballet master Boris Knyazev’s floor barre system was another influence; she used it to work on alignment issues. Her background in Alexander technique also informed her floor work, which then informed her standing work. Somatic education, what Rabin and Loubert called “body awareness work,” was another pillar of the syllabus. The goal was to cultivate a full-time training program for young not-yet-professionals, and in 1985 they co-founded Les ateliers de danse moderne de Montréal. (The school was renamed the École de danse contemporaine de Montréal in 2012.)

By 1991, Rabin’s life had shifted drastically. She woke up one morning and says she heard a voice.

“Linda, if you want to evolve as a human being, you cannot keep doing what you’re doing,” the voice said. “You’ve got to give up dance.”

“I was stuck in a persona that I was projecting, and that was being projected onto me by my students and people of the milieu,” says Rabin. “I was this dance teacher, this choreographer, I worked in a certain style, and people related to me with a certain amount of fear because I represented some kind of authority. I couldn’t carry that anymore if I wanted to open up other doors in myself. And so, I just said, OK, this is it, it’s over.” And she stopped.

***

On a mission to experience life outside of dance, Rabin gravitated to a more internal movement exploration through various somatic practices. She studied experiential anatomy and early human developmental movement patterns with Bonnie Bainbridge Cohen, becoming a certified practitioner of Body-Mind Centering. During that training, she heard about Continuum and founder Emilie Conrad. She describes seeing a video that captured a naked torso “undulating in this most subtle, gorgeous, fluid movement like I had never seen before. It wasn’t performance movement, it was breathing, living movement. It was the life of body tissue. Showing the dance of nature, the dance of the biology that we are.” She calls what she was seeing “the diamond essence of dance, of movement, and that this was my ideal. What I have spoken about from when I was in Japan, looking for this ideal core, I knew that this is what was important for me now.” In 1998 Rabin met Conrad, a deep bond formed, and she became an authorized Continuum teacher.

The work explores how human tissues respond to the vibration of vocal sounds, which stimulate the movement of the fluids within the body. Breath is also key, as is “tuning in to the sensations you’re experiencing within yourself,” says Rabin. She calls Continuum an inquiry into “the movement of life” as it unfolds through our being and the world around us. “It’s a coming together of my love of movement and my interest in the more philosophical mystery of life,” she says. “It’s the idea of being present. You begin to feel an exquisite world of life going on inside the body.” Prieur, a Continuum student of Rabin’s, relates to the work as “a journey of awakening awareness, going deep into the imagination that opens doors for movement, and seeing that interconnectivity with all of life,” adding that in this state of sensorial awareness and exploring the reaches of the imagination, the physical body becomes curious. Rabin’s constantly refining what she manifests for Continuum participants. “These refinements are her great skill as a pedagogue,” says Snelling. “They keep her own questions about the work alive while offering very skilled techniques to students of many different backgrounds and experiences.”

Rabin would also return to the École de danse contemporaine de Montréal, where she teaches a Recherche creative course, guiding students’ personal and creative processes. Contemporary dance artist Nicolas Patry first met her as a student at the school and since has been a longstanding practitioner of Continuum. He’s inspired by her thirst to dive deeply. “She’s very youthful in her approach to teaching,” he says, noting her ability to expand a young dancer’s way of moving and to encourage them to face the unknown with curiosity. For Snelling, Rabin’s teaching is about “what’s really moving a dancer, not how the dancer moves.” And Prieur calls her family. “Linda’s somebody that I will always exchange with,” she says. “She’s someone I’m learning from, sharing life with, and being with in life.”

Rabin frames her teaching and exchange with clarity: “It’s where my life force comes into play.” As for the future, she says it’s still all about evolution. “Part of me is wanting to see what is going to capture my interest. There’s something about my curious nature that needs to keep evolving,” she says. “What lies ahead is unknown.” And with that, a cool breeze wafts across the kitchen.

Sommaire:

L’extraordinaire métier de Linda Rabin : changer les conceptions de la danse et du mouvement au Canada. Au fil d’une carrière prolifique, elle a tenu de nombreux rôles, y compris enseignante de danse – notamment cofondatrice de ce qui deviendra l’École de danse contemporaine de Montréal, – chorégraphe, répétitrice, praticienne de techniques somatiques, mentore, et enseignante de continuum. Ses questions et son écoute profondes touchent des générations d’artistes, et le milieu de la danse canadienne s’en trouve grandement enrichi. Carol Prieur, interprète et élève de longue date, qualifie Rabin de transformatrice. « Elle est perpétuellement en recherche, et cela m’attire », décrit-elle. Sa vivacité, son humour, son sens du jeu et sa perspective nourrissent son charisme. Ses capacités extraordinaires de pédagogue sont inégalées. Comme enseignante, elle est « finement perspicace », nomme Lin Snelling, danseuse qui enseigne, écrit et performe. « Elle conjugue sa sagesse cumulée et sa compréhension du potentiel de chaque personne de façon autonome, et aussi en relation au groupe de personnes en studio. » Elle a 76 ans. Son imagination artistique rallie un sentiment de transcendance spirituelle et une curiosité qui reconnait le mouvement comme la vie. Elle semble avoir toujours bougé, toujours dansé, et elle ne tarit pas. Le mouvement la raccorde au monde. Récente lauréate du prix de la réalisation artistique pour les arts du spectacle du gouverneur général, et de l’Ordre du Canada, son legs croît toujours.

Dance Media Group strengthens the dance sector through dialogue. Can you help us sustain national, accessible dance coverage? Your contribution supports writers, illustrators, photographers and dancers as they tell their own stories. Dance Media Group is a charitable non-profit organization publishing The Dance Current in print and online.

Tagged: