Throughout her history, the ballerina has been perceived as the embodiment of beauty and perfection. She has been a feminine ideal – unblemished and ethereal, inspiration incarnate. But the reality is another story. In her new book, Deirdre Kelly writes about the struggles of the stars of the dance form – from the earliest ballerinas, who often led double lives as concubines to the famous nineteenth-century ballerinas who lived in poverty and worked under tortuous and even life-threatening conditions. In the twentieth century, George Balanchine created a contradictory ballet culture that simultaneously idealized and oppressed ballerinas. Now, finally, change is afoot and in the contemporary era, social and cultural changes announce a new model ballerina. In this excerpt of Ballerina, Sex, Scandal and Suffering Behind the Symbol of Perfection Kelly argues for a rethinking of the dance form and a new understanding and appreciation of its leading ladies.

Ballerinas of the twenty-first century tend to be more muscular and less emaciated than they have been in the recent past. Anorexic chic is no longer in vogue. “Bodies are more athletic looking and more womanly, shapely with curves as a result of muscle mass,” says Beverly Bagg, the South African ballerina now employed as the ballet mistress for Canada’s Alberta Ballet. “The technical demands are such that a ballerina today can’t be thin anymore; she has to have muscle mass in order to facilitate performing to the new athletic standard. She can’t fulfill her obligations as a dancer if she doesn’t have the power. That’s why holistic training is important; it creates a more capable instrument, a more empowered dancer.”

Joysanne Sidimus has staged ballets all over the world. Over the last forty years she has personally witnessed the ballet evolve into a more responsible and socially aware endeavor, repositioning ballerinas’ needs closer to the center of the art: “We’ve come a long way, baby,” Sidimus says. “I am not saying that anorexia no longer exists—you and I know that it does— but companies just aren’t allowing it, anymore. If there are dancers who are overly anorexic they are encouraged to get help, leave until they can get it together again. And the schools are changing: they now have psychiatrists, social workers, nutritionists—the works—on staff, teaching young dancers what it means to be healthy and helping them stay that way. It really is a different world.”

American-born Svea Eklof, who danced with the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, today coaches young dancers at Toronto’s George Brown College, a feeder school for Ballet Jörgen in Toronto. She concurs that the culture is changing—and ballerinas along with it. “There are extreme regulations in place,” Eklof says. “In dance schools in the United States a teacher can’t even say the word weight. It’s not allowed. It’s a result of an attitude change, I think. People have begun to understand that girls between fifteen and eighteen are at the heaviest period of their lives because of hormonal changes within their own bodies. They have to have a little plumpness in order to grow into women. So that’s better understood now, and I think that’s good for the art form as a whole.”

The dancers now being created as a result of this shift in focus “are not sticks anymore,” Eklof continues. “Lean and mean is now seen as better than thin and frail and constantly having stress fractures. It also makes better sense for the art form as well as companies worried about their bottom line. If you have dancers unable to dance because they get injured all the time as a result of brittle bones caused by poor nutrition then you can’t operate your business. So the thinking today is more take better care of the talent and the talent will take care of you, which is a good thing, of course, all around.”

But for every giant step forward, ballet takes two steps back.

In December 2010, the New York Times dance critic, Alastair Macaulay, in his review of the New York City Ballet’s annual performance of The Nutcracker, took umbrage that the lead ballerina was fleshier than the ballerinas he had been used to seeing in his many decades as a seasoned dance observer. In print, he accused the ballerina dancing the role of Sugar Plum Fairy as having eaten one sugarplum too many, a cheap shot ostensibly meant to shame the dancer for having veered away from the skinny norm. Jenifer Ringer, the ballerina in question, a working mom, had, in fact, been battling an eating disorder for years; her curvier body was a result of her having shucked old and dangerous eating habits in favor of new, healthier ones. The critic’s jibes could have set her back. But it was a sign of the times that her public rushed to her defense, writing letters of protest to the paper and clogging the blogosphere with complaints about ballet’s tyranny of thin. It was evidence that the public was all for a curvier, healthier aesthetic. Ringer showed herself to be equally in step with the times, appearing unfazed by the negative scrutiny of her body; she knew it to be an antiquated mindset, a relic of ballet past without relevance or currency. Helping the ballerina perform well—and stay healthy—is science. It might seem a strange dance partner for her to have, but, as Jeffrey Russell, an assistant professor of dance medicine at the University of California, Irvine, points out, without science, ballet couldn’t exist: “Without the physics of muscular force there would be no movement, without biochemistry there would be no muscular activity; you need food to create the energy needed for your body to perform as a dancer. If you take science away, you’ve taken away life itself.”

At the dance research lab he has been operating out of the university’s engineering wing since 2010, Russell applies these rudimentary scientific principles to enhancing the life of ballet dancers as experienced on the stage. The aim, he says, is “to develop dancers to be better at what they do.” Although his clinic cares for dancers hurt as a result of their jobs, the primary focus is on injury prevention. “It’s a lot easier to maintain something than it is to fix it,” he says, using the analogy of a car, which runs better if it gets regular lube jobs instead of being driven into the ground. “When it breaks down, it’s harder to get it moving again. So it’s better to anticipate the problems than let them happen in the first place.”

Russell views injuries as the biggest problem plaguing ballet as a career choice. “That must mean something is wrong,” he says. As is often the case, it takes an outsider to question what, to the initiated, has become accepted practice. “So let’s study what’s going wrong so we can reduce the number of injuries that come as a result of a dancing career.”

Russell works with a research group of eighteen students, and he isn’t the first health practitioner to devote his energies to helping ballet dancers. Many professional dance companies today are staffed with physiotherapists and other health-care workers who help ballet dancers stay in optimum condition. Russell cites the New York City Ballet, the San Francisco Ballet, the Mariinsky (or Kirov) Ballet, the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and the Birmingham Royal Ballet in England as companies where dance medicine is practiced. But Russell is the only dance scientist he knows of working within a university setting, alongside community-based dance programming. At UCI, there are over two hundred fledgling ballet dancers, and they constitute Russell’s main area of study. But his reach also extends into the community; he uses Twitter to advertise his particular area of expertise. He’s a New World doctor working to help an Old World profession keep in step with the times. Why hadn’t anyone thought of it before? “By and large, people don’t consider dancers as athletes,” Russell says. “There is a complete lack of understanding among the general population about what ballet dancers do. People look at them up on the stage and don’t see the effort. They seem beautiful and not really working hard. Dance isn’t in people’s consciousness the same way that professional sport is. The rigors of what they do and the injuries they sustain just aren’t that well publicized.”

Russell did his [PhD] thesis on the wearing of pointe shoes by ballerinas, specifically the cruel damage they inflict, including tendon damage and sprained ankles. At the forefront of dance science, Russell developed an MRI method for evaluating the ankles of female ballet dancers standing on their toes. The scans shed light on the weight-bearing anatomy of female dancers, affording doctors and scientists a rare glimpse at how pointe shoes impact bones, joints, and soft tissue. Together with scientists in England, Russell analyzed the images, comparing them to dancers’ own descriptions of their pain. “I wanted to know the demands of ballet on the ankle and the foot. What are the stresses imposed by the pointe shoe?” It was a breakthrough study, which not only showed “how the musculoskeletal system responds to dance” but also furthered “progress toward the ultimate goal of reducing injuries.”

“After examining the MRIs of ballerinas, I can tell you that dancing on pointe is not at all good for the ankle,” Russell says. “But the pointe shoe is not going to go away. It would alter the art of the ballerina far too much. So what we can do is help dancers dance to the best of their ability within the confines of ballet and not be sidelined by injury.”

It’s a radical objective—and also a tricky one. Ballet dancers are slow to give up past practices; their art form is rooted in tradition. Ballet history is passed down from one generation of dancer to another, thereby maintaining its classical lineage. But there is an unforeseen problem with older-generation dancers teaching their successors how to perform ballet as they once practiced it; their instruction often comes encased in bad habits that help perpetuate ballet as an injury-prone profession.

“There’s an old-school line of thinking that physical training will ruin the ballet aesthetic,” Russell says. “In terms of generations, we’re still in a situation where the ones teaching the younger dancers are those who came through a system where there wasn’t much being offered in the way of physical training or even healthy dance practices. In their day, you just did what you did, and if you got hurt, tough. It really comes down to you teach what you know, and if that includes suffering for your art then that’s what’s also being passed down. It will take a major paradigm shift for the average ballet teacher to want to teach ballet in a different way.”

In other words, what often needs fixing most is a mindset. Besides dance teachers, Russell’s biggest challenge remains convincing dancers to set aside time for strengthening and conditioning exercises that will help lessen the number of injuries they sustain in the course of their work. “There are only twenty-four hours in a day, and I understand that for a lot of dancers carving out time to do cross-training isn’t a priority. The typical dancer is going to spend the bulk of that day per- fecting the craft.”

But reducing the amount of time given over to technical training in favor of core physical training actually does result in making dancers better artists. Heightened technical achievement in dancers can now be proven to be directly related to a stronger physical foundation. But that’s just the tip of the pointe shoe, so to speak. Russell says more needs to be done to help ballerinas of the future become even stronger as artists and more gifted as athletes. “We’re about twenty years behind sports medicine,” Russell says. “In terms of research, we’re still a number of years away from saying this is what we think is useful. And it will still be a difficult thing to get across to people used to working in the old way, especially because ballet has traditionally not been an area attended to by science. So it’s tough. But I’m going to stick with it. It’s my calling. I do see that I am making a difference. I think I am helping the ballerinas of the future.”

It is a clarion call also to companies to make it their mandate to safeguard the art of ballet for future generations. It starts with a shift in perception, seeing the ballerina not as a slave to her art but as a valuable employee within the juggernaut of the professional ballet company. Such is the thinking of an enlightened troupe like the Australian Ballet. There, ballerinas are perceived as elite athletes and are treated as such.

In 2007, the Australian Ballet implemented a company- wide Injury Management and Prevention Programme aimed directly at dancers’ health. The program came about as a result of ballet culture as a whole becoming more aware of medico- legal and liability issues. According to the company’s published mission statement, the aim is to do away with the days when ballerinas would bleed into their pointe shoes and no one would care, replacing a culture known for its abuse and neglect of dancers with one that sincerely cares about their overall health and well-being.

Management regularly counsels dancers that injuries are not to be swept under the carpet or ignored for fear of reprisals. This concern for dancers’ health is written into the company’s policy: “The Australian Ballet has demonstrated to the dancers that reporting injuries does not disadvantage them in any way; on the contrary, everything is done to ensure that dancers are not restricted from their pre-injury status.”

But it’s a two-way relationship, says Australian Ballet artistic director David McAllister, a former principal dancer with the company: “I see it very much as a shared responsibility. We have tried to build a culture within the company where the dancers are proactive about injury prevention and report any niggles early so we can treat them and avoid long-term periods away from the stage,” he says. “We have also built a great collaboration between the medical and artistic teams so we have shared responsibility about workload for dancers, so that we can keep them dancing but modify their load to avoid progressing to a major injury. But you can only do this with dancers who present early and don’t hide injury. They also need to make sure they are doing all the strengthening and technical coaching work and take responsibility of their own bodies; otherwise you will only be able to patch up.”

The Australian Ballet takes a multidisciplinary approach to injury prevention; in the wings, at the ready, is a kind of Team Ballet, composed of various physiotherapists, myotherapists, masseurs, sports doctors, rehabilitation facilitators, body conditioning specialists, psychologists, and alternative medicine practitioners doing needling and other forms of acupuncture, devoted to ensuring that all dancers are performing at peak condition. Addressing dancers’ needs extends also to ordering special pointe shoes for a ballerina whose feet might be vul- nerable to tendinitis or stress fractures. Great care is taken to ensure that they have healthy and strong bodies, a balanced diet, and sound nutrition. Dancers are also encouraged to have open communication with management in discussing their needs and concerns.

Principal dancer Amber Scott credits the open-door policy and the access to pertinent scientific knowledge as enabling her to have a long and rewarding profession: “It’s a grand statement but I believe the medical team and body conditioning programs at the Australian Ballet have been paramount in keeping me dancing professionally for the past eleven years,” Scott says. “The combination of very specific treatment, body conditioning and coaching all unite in a way that educates the dancers to understand the capability of their bodies in a safe environment. The open channels of communication between all departments have been key for learning as much as possible from the medical team. This knowledge has taken away many of the fears I had about injuries. It has empowered me in my quest to maintain a long and healthy career.”

~

But even with injury prevention programs in place, acci- dents do and will happen. Ballerinas can pirouette into the orchestrapit, be hit by falling scenery, be dropped by their partners, or, as was common in the past, catch fire. They can also injure themselves from overuse and as a result of poor training or unsafe choreography. Injuries are worrisome because they can terminate a career before a dancer feels ready to quit. Claire Vince, a member of the National Ballet of Canada’s corps de ballet from 1989 to 1992, had to stop dancing after only four years as a result of a deteriorating hip: “The cartilage on the right hip had worn out from repetitive use, “ says the Australian-born Vince, who trained at England’s Royal Ballet School. “Dancing was so painful for me at the end that I couldn’t do developpés.” After moving back to Australia, she had hip replacement surgery. But before that, while still in Toronto, she had what she calls “a big operation on both ankles,” to address os trigonum syndrome, a medical condition caused by repeated downward pointing of the toes, as is common in ballet. Surgeons had to remove excess bone from the back of Vince’s ankles: “Effectively, I had to have the ankles broken, the bones removed, then go in plaster for six weeks,” she says. It sounds horrific, but Vince is matter-of-fact about what she endured as a result of ballet, calling her injuries “a part of a dancer’s natural term.”

Today pain free, Vince has a new career in public relations. But for most ballerinas, when the dancing stops, they often are at loose ends. They don’t know what to do next. The pain that lingers lies within. The celebrated Canadian ballerina Evelyn Hart, formerly the prima ballerina of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, has described the abrupt conclusion of a dancing career as a loss of identity, a loss of expression: “I feel I have no voice left.”

When Joysanne Sidimus stopped dancing in 1970, she plunged into a deep depression. “It was a terrible time,” she says. “I went home to my mother’s and went to bed for six months; I didn’t get out of bed because I didn’t have a reason: My whole life was falling apart.” Having experienced first- hand the pain and desperation endured by dancers forced to leave their professions because of illness, injury, or incompatibility with an artistic director, Sidimus soon inquired after some of her colleagues, to see how they were coping with the break from ballet. What she heard shocked her; fifteen of herformer partners had committed suicide and another had been committed to the psychiatric ward at New York’s Bellevue Hospital: “I wanted to do something.”

In 1985, Sidimus founded the Dancer Transition Resource Centre, a forward-thinking facility in Toronto providing career counseling, legal and financial advice, grants, and other sup- ports to dancers needing to regain their moorings after being cast adrift from the stage. Since its founding twenty-five years ago, the center has gone on to help more than ten thousand dancers move into second careers in academia, arts administration, medicine, law, graphic design, engineering, public relations, and real estate. One dancer who went through the center became a commercial pilot.When it first opened, the center was radical for its time. “When we began, the issue was taboo for most dancers,” Sidimus says. “To end a performing career was something most dancers feared and did not wish to discuss or face.”

The physical demands are so tough on the body and injuries in ballet are part of the job description. To withstand the wear and tear, a dancer needs youth on his or her side. The average age of retirement for ballet dancers today is twenty-nine. For modern dancers it is forty.

“More than any other professional, with perhaps the exception of athletes,” Sidimus says, “dancers don’t have a choice. Early retirement is built into the profession, and there’s no way around it.” In general, Sidimus adds, dancers are forced to give up their careers at a time when most other professionals are just starting to take off in theirs: “As a psychologist who works with us at the Centre says, ‘Dance is a downwardly mobile profession in an upwardly mobile society.’ David Tucker is a psychologist who worked closely with retired professional hockey players through the Phil Esposito Foundation in Toronto and served as a consultant to Sidimus when she was first establishing the Dancer Transition Centre. “The problem with professional athletes and dancers is that for all their lives they have been so focused on their careers, they don’t know where to even begin looking for a new job,” said Dr. Tucker at the time. “Often they feel desperate and will grab the first thing that comes along. It’s important that they think these things through so as to save themselves perhaps even greater aggravation later on.” The stigma is lessening, and Sidimus sees that as anothersign that the ballet culture is changing in ways ultimately beneficial to the ballerina: “The whole subject is now out of the closet; people are now talking about it and they are doing something about it. If a dancer has a transition plan at the beginning of the career, knowing in advance that it is short, it takes some of the anxiety away. It helps dancers be better at what they do.”

Still, retirement for dancers is like death: a scary prospect. Aware that dancers are spooked by the prospect of letting go of the one thing they have trained their whole lives for, the center and its half dozen branch offices across Canada offer its dancer- clients the services of onsite psychologists, psychiatrists, and sociologists to help them through a time in their lives that can be quite disorienting.

Indeed, in ballet, as one dance writer has wryly noted, “There are few stories like that of Nora Kaye, one of the brightest stars of American Ballet Theatre, who reportedly celebrated the event by driving with her husband through the Black For- est of Germany, happily hurling her old pointe shoes through the window of their car.”

When Sidimus started investigating the post-dance lives of her former colleagues for her 1987 book, Exchanges: Life After Dance, a collection of interviews with dancers who have successfully moved on from the stage, she discovered insteadthat the majority were shell-shocked and destitute. “Many of these people were founders of dance companies. They have the Order of Canada, and yet they have nothing to live on,” Sidimus says. “There aren’t hordes of them, but you would be shocked by the names.”

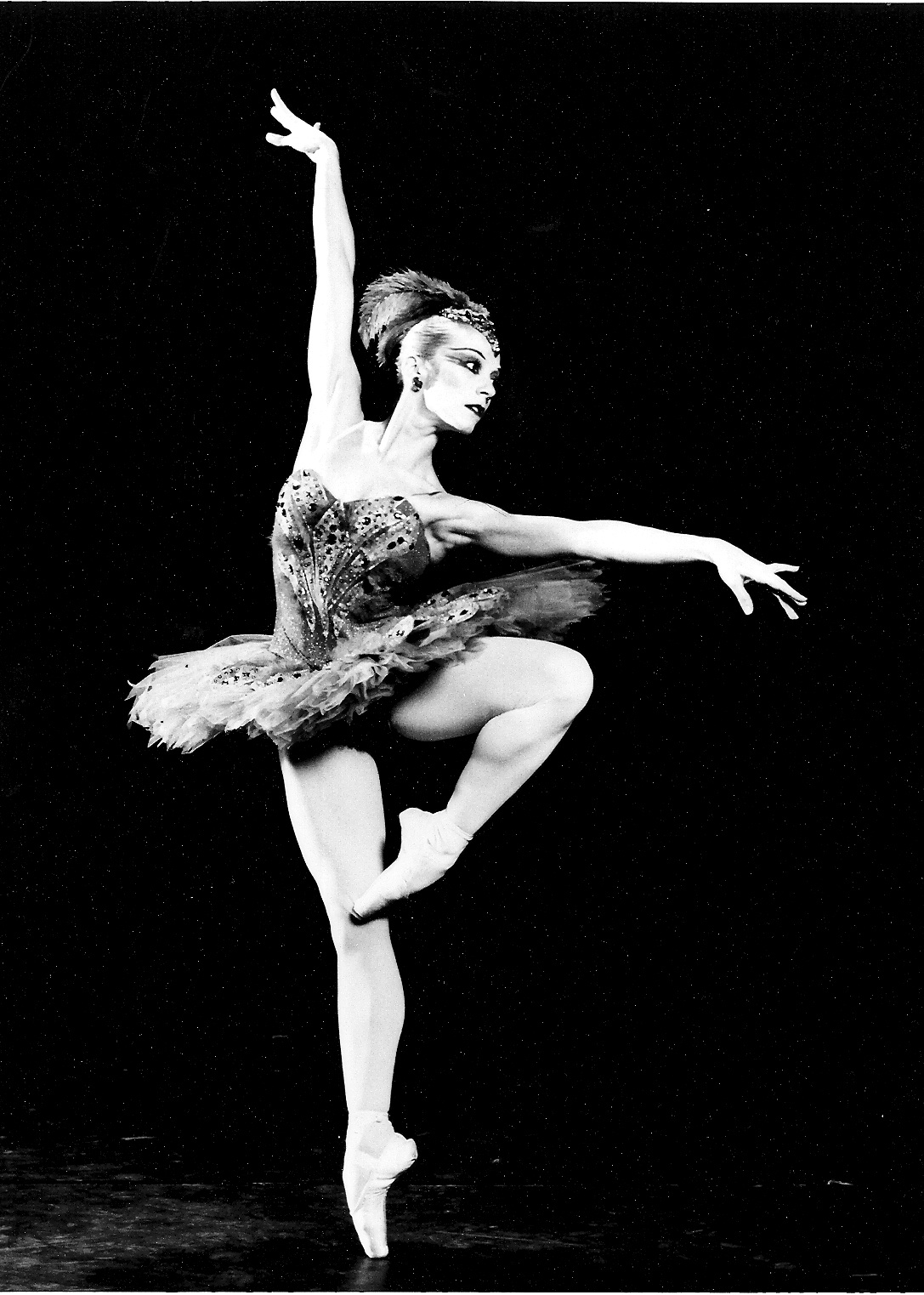

Evelyn Hart is a poignant example, as well as a reminder that more still needs to be done to safeguard the ballerinas of our time. Born in Ontario in 1956, she won the Gold Medal and the Certificate for Artistic Achievement at the International Ballet Competition held in Varna, Bulgaria, in 1980. During her years on the stage, from 1977 until her abrupt departure in 2006 as a result of arthritic ankles, Hart was internationally regarded as a consummate artist; in the 1980s, she toured Russia and other Eastern Bloc countries, where audiences and critics alike hailed her as one of the greatest Giselles of the twentieth century.

Her artistry had come at a great personal price. Hart made no secret of having approached ballet as an act of self-sacrifice; she starved herself to be what she perceived as an expression of balletic perfection and denied herself intimate relationships, including marriage. She spent most of her waking hours in the ballet studio, devoting every ounce of her being to perfecting her craft. Those who danced alongside her at the RWB during the 1980s still marvel at the single-mindedness with which Hart pursued her career, to the exclusion of everything else.

“She was unique in her approach, almost neurotic but in a good sense of the word; her process didn’t allow for anything else in her life,” says Svea Eklof, who shared a dressing room with Hart when both were with the RWB. “She was known to say, ‘You are not as deep into this [meaning ballet] as I am; that’s why you took time off to have a husband and to have a baby.’ She said it, and she meant it: She is the best dance artist that Canada has ever produced.”

But when the curtain came down on her final performance in2006, Hart, then fifty, was suddenly unemployable. Although she was a recipient of the Order of Canada, she had no assets other than a highly disciplined body blessed with a rare degree of musicality. She tried acting but didn’t have the articulation. She applied for a job in a bridal salon, making and selling the fanciful headdresses that she used to craft as part of her onstage costume but was turned down for lack of experience. Save for a handful of students who have come to her privately for coaching, Hart’s own profession has been reluctant to hire her as teacher or coach; the perception within her industry is that Hart represents an old-school, tunnel-vision approach to ballet, which is contrary to the new emphasis on life-work balance that many of today’s ballet institutions say they want to instill in their students. Certainly, to see Hart is to see a woman ravaged by her profession—thin, alone, and invisible in a crowd now that her dancing career has ended. This is an artist who, just years earlier, had full houses leaping to their feet, cheering and showering her with roses. That she has been so abandoned by her profession and by society is a great scandal. Had she lived in another era, her selfless devotion to ballet might have been lauded. But today, she is no doubt one of the dancers Sidimus is talking about: a jilted female not unlike Giselle, a ghost of her former self.

Sidimus says she has been lobbying for years to get funding for artists like Hart, dancers she calls “national treasures,” urging Canada to provide for them in retirement as other countries have done for their senior dance artists. It would be respectful, at the very least, to create for ballerinas who have given their lives to their art the respect of a position worthy of their experience and training, a chair within a university dance program, for instance, where they could pass their artistry on to the next generation. Shunning dancers because they are old and put out to pasture is a shameful way for any nation to treat its artists. “There’s something about a dancer in transition that is exceptionally difficult and painful and different from anyone else in transition,” Sidimus says.

Previously, the ideal in ballet was to pretend that you would keep on dancing until you dropped—as Anna Pavlova and Rudolf Nureyev did. While romantic, this image of the swoon- ing dancer, shackled to the art, no longer cuts it in today’s climate of economic restraint. “The average annual salary in Canada is still under $14,000 for a dancer,” Sidimus says. “They can rarely put enough money aside to live on while they study something else for a second career.”

Sometimes a dancer has to leave dance because of an injury that never quite heals.

“In the past twenty years I’ve seen a lot of heartbroken people,” former National Ballet of Canada dancer Karen Kain, now the company’s artistic director, has said. “They had trained, almost killed themselves, given 150 per cent—and suddenly it was all over. There was nothing for them. I’ve seen nervous breakdowns when people’s dreams were shattered. There were people who came into the company with me, and I’ve seen them fall apart.”

Leanne Simpson was one of those dancers, devastated when the dancing was over. The former ballerina with the Alberta Ballet and Les Grands Ballets Canadiens who quit dancing in 1988 said in an interview, “I was very depressed. After five months, I called the Transition Centre.”

Through the center, Simpson received counseling and then went to university, where she chose a new career, teaching in an arts school. To help her, the center gave her grants that helped cover expenses for two years of her post-dance training.

“I feel much better now,” Simpson said. “I still miss performing, but I feel that I fit into the real world now.”

Mary Jago-Romeril sees many dancers like Simpson in her position as a national representative of the Dancer Transition Resource Centre, a position she has held since 2002. From her vantage point, she is able to see how dance has changed since she was a principal dancer with the National Ballet of Canada, from 1966 until her retirement from the stage at age thirty- eight in 1984. During her illustrious career, the British-born, Royal Ballet–schooled ballerina was celebrated as one of the Fabulous Five, a group of top-ranking female dancers, each of whom had been handpicked in the 1970s by guest artist Rudolf Nureyev to dance as his partner in his extravagant and costly version of The Sleeping Beauty. The others in this pack of elite ballerinas were Nadia Potts, Vanessa Harwood, Veronica Ten- nant, and Karen Kain, all of whom toured with Nureyev as part of their National Ballet duties, an experience that inspired camaraderie among the dancers: “In my day, being in a ballet company was like family,” Jago-Romeril says. “You looked out for each other.”

Touring isn’t as common for ballet companies anymore; the costs have grown prohibitive, and few companies can afford it. As a result, today’s dancers don’t get to play the field as much as Jago-Romeril once did; they have tended to become more specialized, dancing full-out only a few times during a perfor- mance run, not every night, as Jago-Romeril used to, under her stage name, Mary Jago. She wonders if that is why she is see- ing an increase in injured ballet dancers. “There’s not enough consistency,” Jago-Romeril says. “Dancers no longer get to dance every day, which puts them at greater risk of hurting themselves.”

Although it is definitely beneficial to commit resources to helping dancers cope with the inevitability of injuries in the course of their profession, perhaps a more effective approach for companies to take would be to address the problem of injuries at its root, get dancers more exercised, expose them regularly to performance opportunities, large or small, so as to keep them resilient. This would require a rethinking of how ballet is organized and produced. There’s innovation now in choreography. How about a similar level of innovation applied to ballet administration? But there are no easy solutions. How do you get dancers to dance more, when ballet companies in general struggle to make ends meet? How do you keep them from being injured when taking physical risks is a key component of the profession? How do you strike a balance? [Mary] Jago-Romeril, [at the Dancer Transition Centre] doesn’t pretend to have the answers, but she does express concern that the current emphasis on experimen- tation in ballet puts dancers at a greater risk of injury, especially when their bodies haven’t been trained to perform the new multi-step, hyper-frenetic, acrobatic-style creations being produced by some of today’s cutting-edge choreographers. “What we have noticed today,” continues Jago-Romeril, “is that choreographers are pushing dancers more than they did in previous years. In my day it was basic classic. Today’s choreographers are emphasizing a contemporary approach, and actually I feel sorry for the dancers performing it: Ballet is now very hard.”

But on the bright side, and partly as a result of diminished touring opportunities that have turned ballet dancers from nomads into people who can lay down roots, Jago-Romeril says that there’s a greater acceptance of the need for dancers to balance their workload with a life outside the studio. She cites the example of the National Ballet, where several principal dancers in the company over the past decade have started families, while still pursuing a full-time dancing career. These new-generation ballerinas are now taking advantage of paid maternity leaves and job protection. “And that’s a huge step forward,” Jago-Romeril says. “Today’s dancers have families if they want them, they have children. I think that’s important because it puts a different focus on your life, it’s not all about ballet. Human beings need balance,” Jago-Romeril concludes, “no matter what they do for a living.”

The advancement of workers’ rights has liberated women in all professions, including ballet, where pregnancies among professional dancers are increasingly common. Increased wages combined with guaranteed paid maternity leaves as required by law have provided incentives for dancers to want to start families while still pursuing a dance career. These relatively recent changes in labor law and general societal attitudes have brought artistic directors on board in giving ballerinas leave to have babies in the understanding that their jobs will be waiting for them when they are done. “For me it’s a miracle,” says Sidimus who, at seventy-three years of age, is a member of ballet’s all-or-nothing generation, having waited until her dancing days were over, at age forty, to have a child. “In my era it was a much more isolated view. You were expected to be a ballerina and not anything else. Today when I look at a dancer like [National Ballet of Canada’s] Sonia Rodriguez, a principal dancer who is also a mother of two, I really do wonder how she manages to do it all.”

It’s not entirely a mystery. Advances in health sciences like nutrition and body conditioning have enabled dancers to fully recover their dancing form after childbirth. Cross-training involving Pilates, yoga, and weight lifting has also helped ballerinas cope with the demands pregnancy places on their bodies, enabling them to stay supple and dance well into the last trimester. Some ballerinas claim that motherhood has made them better dancers, physically, mentally, and emotionally: “I feel stronger,” said Julie Kent the American Ballet Theatre ballerina who, in 2004, posed pregnant on the cover of Dance Magazine, dressed in flowing white chiffon and a skintight white leotard that showed off the voluptuousness of her rounded figure. She was thirty-three. “Motherhood has changed my priorities and impacted my performance,” Kent continued. “It has liberated me and broadened my perspective. I don’t apply as much pressure on myself and I have blossomed.”

Motherhood, muscle building, and healthy weight gain are changes directly affecting the ballerina’s body, making it feel more in balance. But ballet is not composed of just one body; it is also a social body, a tightly knit network of human relationships where imbalances have for a long time been allowed to proliferate unchecked, in the mistaken belief that to change one aspect of ballet is to change the culture as a whole, killing in it what has long been regarded as beautiful. This is especially true with regard to racial imbalances within the ballet culture. For centuries, and continuing into the present day, ballet has widely been regarded as a white, elitist, European pursuit. Its symbol is the ballet blanc, literally the white ballet, an ethereal dance performed by white women in white dresses and pointe shoes pretending to be ghosts or swans or something equally vaporous. But society today is rapidly diversifying, especially in immigrant-rich North America, and this image of a white ballet is deeply unreflective of the social composition.

Ballerinas of color, especially black ballerinas, tend to be rare. The thought is that audiences won’t readily accept a black Giselle or a black Aurora, thinking she is too obviously cast against type. It’s a ridiculous premise: ballet is theater and the- ater is make-believe. Of course a black ballerina isn’t Giselle: it’s a role. But there’s another prejudice at work: black women on the stage are perceived as naturally earthy and robust; they are not the airy sylphs more easily embodied by their white counterparts. There perhaps is a reason for this: scientific research demonstrates that black ballet dancers typically have not fallen prey to the anorexia epidemic that swept the ballet world during the Balanchine era. According to one study, black female ballet dancers had a more consistently positive body image than white female ballet dancers, leading to the conclusion that anorexia nervosa is “a disorder of the white upper-middle- class, where a premium is placed on the pursuit of thinness.”

Misty Copeland supports the statistic. A ballerina of African-American descent, she says that she never suffered from an eating disorder, even while her teachers and her white class- mates chided her for being big—“big” being relative given that the dancer stands five feet two inches and weighs a mere hundred pounds. “I never had an issue with an eating disorder,” says Copeland, a rising star at American Ballet Theatre who is also the first black ballerina soloist in a major company in decades. “I can’t imagine dealing with that or having to speak up about it,” she continues. “But I’m definitely not fat; I just have a different body type than all the rest. I am thin, but I have muscles and I have curves and I have breasts—I’m a size 30D.”

Her curves allow Copeland to stand out on stage, which ultimately is a good thing: “I think it has given me an advantage,” she says. “It has allowed me to develop as an individual, which is often hard to do for ballet dancers. From a young age we are groomed to be in a corps de ballet, all trained in the same technique and expected to look the same. I tried as a student to be the dancer others wanted me to be but I found that it was better for me to be me; it’s what has enabled me to become a soloist and, hopefully, it will help me become a principal dancer, which is my goal.”

But to get ahead, Copeland says that she has to work extra hard to appear worthy of promotion: “My skin color was never before a factor for me,” says Copeland, one of six children born to a single mother who raised her kids in Los Angeles after moving there from Kansas, the dancer’s birth city. “I only saw my color when I started to dance. Still, I was a dancer. I wasn’t a black dancer. It wasn’t until I moved to New York City and joined ABT was it talked about. I wasn’t aware it was an issue. And then I looked around me—and oh my gosh—there were no other black ballerinas but me. I still wouldn’t have thought it mattered, but then I watched as others were promoted ahead of me, given roles that I could easily have done but wasn’t allowed to. And that’s when I realized that my natural talent wasn’t enough. As a black woman I have to work three times harder. I have so much to prove. I’m extremely exhausted. I’ve been doing this now for eleven years.”

But her hard work and tenacity are paying off. In December 2011, Copeland received word that Russian choreographer Alexei Ratmansky, said to be the most important choreographer working in ballet today, had cast her as the lead in his new production of Firebird, which had its world premiere in Los Angeles, Copeland’s hometown, in April 2012, to glowing reviews. “I’m ecstatic,” the dancer says. “Ballet will never be perfect, but for me this is about as good as it gets.”

Another indication that ballet might be moving in new directions is the increased popularization of ballet as entertainment. These days the art born in the courts of kings is showing up at the movies, on the fashion runways, and in rock and rap music videos by the likes of Kanye West, whose 2010 single, Runaway, came with a thirty-four-minute promotional film featuring ballerinas aggressively stabbing the ground with their pointes: “I was just moved by the classic dance,” the rapper told MTV News, “I just wanted to crash it against the pop music.”

As a black ballerina trying to break down barriers herself, Copeland understood what the pop star was after, saying in an interview that by mixing ballet with pop music, West was making classical dance “relatable to the audience that’s viewing those videos.” The expectation was that it would increase audiences for ballet, one of the reasons Copeland agreed to dance in the 2009 fever-dream video for the single Crimson and Clover by Prince. Copeland was also the featured ballerina in the pop star’s Welcome 2 America tour, which played Madison Square Garden and New Jersey’s mammoth Izod Center in the early part of 2011. Copeland says working with Prince was both a career and a confidence booster: “It signaled my growth as an artist; it made me more visible to others as a role model.” Her bravura style of dancing was readily accessible to stadium audiences for whom ballet remains a foreign word. Copeland lured them in. “I think that there’s so much history when it comes to classical ballet—it’s not going to change overnight . . . [but by] inviting people in and exposing them to the fact that classical ballet doesn’t have to be uptight . . . I’m hoping that change can happen.”

“Classical ballet needs great interpreters,” says Sylvie Guillem, the former étoile of the Paris Opéra Ballet and principal guest artist of London’s Royal Ballet, the ballerina other ballerinas still look to for inspiration—a YouTube darling. “It can’t be done in a mediocre or average way, even if danced very well. Like it or not, ballet comes from the past; we have to drag it from the past into the present, and if it is not danced intelligently, not danced with beauty, the people will no longer come, and ballet will not survive into the future.”

But ballet is not breaking with its past; it is renewing itself, while at the same time drawing inspiration from a long tradition of classical dance. Embodying that feeling of continuity and regeneration in ballet today is former ballet star Gelsey Kirkland, among the first to lift the veil on the art of the ballerina as a punishing life of self-deprivation and self-sacrifice in the name of beauty. To many observers, Kirkland is the poster girl for all that is wrong with ballet—eating disorders, injuries, insecurity, exploitation, and a dissolute lifestyle. Kirkland lived it all—and more. She altered her anatomy to make herself more closely approximate the ideal ballerina. The sad irony is that Kirkland was already a rare specimen of balletic excellence— and a beauty as well. A dancing prodigy who entered New York City Ballet in 1968, at the tender age of sixteen, after being trained by George Balanchine at his School of American Ballet, Kirkland was born with the requisite long-limbed body type, the swan neck, the hyper-flexible feet. Her speed, grace, and agility survive in films and videos of her earlier performances, especially the 1977 film version of Balanchine’s The Nutcracker, in which she dances opposite her former onstage and offstage partner, Mikhail Baryshnikov.

Often referred to as the female Nijinsky for her genius for dance, this American-born ballerina was one of the great ballet artists of the twentieth century. Ballet patrons who remember her when she was at the peak of her powers shake their heads and speak of her as the ballerina who squandered her talents. They want to think of her as one of the neurotic pinheads of the Balanchine era, a malcontent who exaggerated ballet’s dark side as an act of morbid self-promotion. They see her as twisted and irreparably disconnected from ballet as an art of beauty and transcendence. But the opposite is true. After dancing in the trenches of ballet, Kirkland has emerged, scarred but wiser, and is today channeling her remarkable gifts into her own Gelsey Kirkland Academy of Classical Ballet, which she founded in New York in the fall of 2010, at age fifty-eight, to train young dancers for a professional dancing career.

Located on Broadway, in Manhattan’s industrial TriBeCa district, the dance school perches incongruously over a dusty fabric shop and next to scaffolding emblazoned with graffiti. It’s only a subway ride away from Lincoln Center, where

Kirkland once ruled as one of America’s reigning ballet super- stars, but in many ways it is light years away from the life she once knew. She runs the school with her husband, Michael Chernov, an Australian-born former dancer and Broadway actor, who trained at the National Ballet and Theatre School in his native Melbourne. The interior walls are covered in framed oversized vintage posters from the Diaghilev era; another image, of Kirkland dancing opposite Baryshnikov in Balanchine’s The Prodigal Son, serves as a computer screen saver. There are four studios spread over 8,000 square feet of high-ceilinged space, in addition to an exercise room teeming with workout machines and balls and bands for core training. The Russian-based training is rooted in the Vaganova method of teaching ballet, a combination of French lyricism and Italian virtuosity as developed early in the twentieth century by former Imperial Ballet dancer-turned-pedagogue Agrippina Vagonova. Each day begins with a morning yoga-inflected stretch class using mats on the floor. This is followed by classes in ballet technique and also, unusual for a ballet school, voice and drama.

The emphasis in her pedagogical approach is on storytelling through dancing. Abstract ballet, such as Kirkland knew in her Balanchine ballerina days, is not the objective. Kirkland wants her sixty-four registered students to learn how to move from the heart, to connect with audiences emotionally as artists using their bodies expressively, not as athletes performing acrobatic tricks. The divide between expressiveness and pyrotechnics has existed in ballet for centuries, at least since Camargo, the technician, and Sallé, the poet, ruled the stage. Kirkland has no doubt as to which rival she supports. In conversation, she uses words like pure and truth to emphasize that her training is less image oriented, more focused on inner states of being.

“You can’t drive the body from its form,” she says. “There are other ways of creating a stage life.” She wants her students to connect to the inner core of ballet and not be distracted by the allure of the superficial attractions of the art, a lesson she must have learned herself the hard way. One technique used at the school is to have students dance in the studio with the mirrors covered, getting young dancers to concentrate on what it feels like to dance, rather than on how it looks to somebody else. It is the opposite of how Kirkland and other ballerinas of her generation learned their craft, and she is determined that her students don’t make the same mistakes. Taking her place in the studio on a busy Manhattan morning, Kirkland is dressed head-to-toe in black, over which is layered a button-down shirt flapping around her small, birdlike body. She moves silently around her cavernous academy, looking as if she could suddenly take flight. Kirkland covers most of her face with large Jackie O–style sunglasses; her fine auburn hair is tied back in a chignon. When she opens her mouth to speak the words come out nasally and in staccato bursts, pushed through the cushiony contours of distorted lips, a reminder of her days as a tortured artist. It’s her reputation as a complex ballet genius that draws students to her from across the United States. They choose her academy over larger and more prestigious schools like Juilliard or Kirkland’s own alma mater, School of American Ballet, because they believe she has something valuable to teach them, no matter how negative her own past experiences of ballet.

“I am inspired by her,” says Jacqueline Wilson, a twenty- one-year-old dance student, who traveled halfway across the country to study with her ballerina idol. “I grew up with a blown-up poster of her on my bedroom wall. She represents ballet to me.” In Kirkland’s morning technique class, Wilson takes her place at center floor in front of the watchful eye of Kirkland, sitting like a Buddha on the edge of a stool at the front of the studio. The dancers come in all shapes and sizes— tall, short, svelte, muscular. Kirkland is easily the tiniest person in the place; her waiflike look definitely marks her as senior, her body having been shaped by the eating disorders that have plagued her profession. But she has moved beyond the tyranny of that aesthetic. During a lunch of a homemade sandwich laced with onions—“You’re not bothered by the smell, are you?” she asks, betraying the kindness that those who know her say is one of her most unsung attributes—Kirkland explains that the point is no longer to create dancers who all look the same. It’s about creating dancers who are unique, with something of their own to say. She had learned the hard way the mistake of trying to conform to someone else’s idea of what a ballerina should look like and is now passing on the benefit of that experience to her own students. In one of her studio’s classrooms, in fact, a curtain has been drawn over the mirror to get the dancers to find meaning within themselves, not in a reflected image. “A perfect body can be dead as a doornail,” chimes in Chernov, allowing his wife another bite of her brown-bagged meal. She sits beside him, nodding in agreement. “The idea is to get people out of ballet’s image orientation,” he adds. “The ideal,” says Kirkland, swallowing, “is to explore what’s true.”

Back in the classroom, Kirkland provides an insight into what she means. Perched slightly forward on her stool, ready to pounce, she watches her dancers in ominous stillness as strains of Tchaikovsky fill the air from the accompanist in the far corner. “Draw the line on the way out, open the door,” she shouts above the music, her hand beating time on one thigh. But the dancers are having difficulty understanding. She leaps up from where she has been sitting to give an impromptu demonstration. The once famous body pulls up and lengthens. All the weight is pushed forward onto the balls of the feet, and she rises slightly into the air. She opens her chest wide, her arms blossoming into an elegant port de bras. Her head is slightly tilted; her eyes are raised. “To the king,” she says. And then she bows slightly to this imaginary being in the room, looking down from on high.

It’s an extraordinary gesture. In that moment, all the minutes, the hours, the months, the years, the decades, the centuries go whizzing by. We are no longer in traffic-clogged Manhattan, with the horns blaring outside the window, the graffiti spray-painted on the wall, a pretzel cart on every corner. We have gone back in time to the opulent court of Louis XIV, where this glorious art of ballet first flourished more than four hundred years ago.

Kirkland provides a link, a ballerina who through her own training, stage experience, and tortured past is showing the way for how the art can proceed from a troubled history into a more hopeful future—a ballet survivor.

“There’s a lot of rigidity that frees you,” Kirkland says. “There are ways of using tradition to move forward and not sideways. It’s about knowing what matters, and following the right path.” In Kirkland’s hands, the catastrophes that have befallen ballerinas through time have been channeled into catharsis.

Excerpted from the book Ballerina: Sex, Scandal, and Suffering Behind the Symbol of Perfection, © 2012, by Deirdre Kelly. Published in 2012 by Greystone Books: an imprint of D&M Publishers Inc. Reprinted with permission of the publisher.