Crystal Pite’s new show Uncollected Work, by Pite’s recently formed modern dance company Kidd Pivot, is presented in two parts and bravely adopts the notion of the creative process as thematic material. Although many writers, visual artists and psychologists have attempted to expose the workings of the inner mind during creative process, we were intrigued to discover how Pite would approach such ideas with movement. What follows is an exploration of our respective understandings of the dance work through dialogue and the writing process.

In the text following, Mari writes in plain text, Imogen writes in italics and Crystal writes in bold.

I’d like our readers to feel acquainted with this work, through our writing, but for starters, will they understand the title we hatched for this article, Mari? It’s an ugly duckling, I know, but ironically, it does bring to mind some of the exquisite and unusual dancing we saw a raw and expressive syntax made from a shiny new alphabet.

I agree there is intent in the choreography to access movement in an innovative fashion, but I don’t see a new vocabulary, Imogen. That would be radical. As for the title, the reference will soon become clear.

The program notes inform us that the piece is inspired by Annie Dillard’s book “The Writing Life”, a writer’s account of the creative process. From the get-go, there is no guessing, no wondering what the work is all about. Pite wants us to know. And so, we all come together at the outset, focussed and attentive to the journey, or perhaps problem, before us. Uncollected Work consists of two full-length pieces, part one “Farther Out” and part two “Field:Fiction”. The quest begins in “Farther Out” with a black manual typewriter suspended by wire cable over the dance floor, signifying the thematic concern of the choreographer. The skillful use of Dillard’s voice, commenting on the nature of writing, maps out the performance terrain and, together with Owen Belton’s mesmerizing electronic soundscape, provides a satisfying guide to the problem of structure. Pite and fellow performer Cori Caulfield succeed in creating bold images with the use of their bodies in physical relationship to theatrical sets and props. I don’t think I would agree that it’s a new lexicon. But, certainly it is expressive, and the way the content is organized is clever. In retrospect, the work seems to employ a curious movement syntax that combines image-based dance theatre and a choreographic lexicon that is a response to the Dillard text.

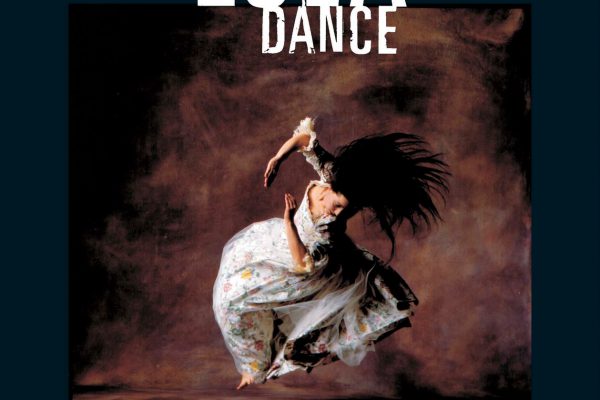

Pite’s approach to expression has intellectual bite but also a corporeal softness that informs her dance regardless of external cues. In visceral terms, she articulates her spine like a length of chamois cloth, snapping, folding and linking the internal body to the demanding contexts created by her choice of props, text and sound. Appearing relaxed at first, her red-cheeked and innocent presence grows flustered and temperamental in the face of this turbulent arrangement of elements.

Yes, and it is the performance of part two, “Field:Fiction”, that is more compelling in terms of the invented images that the set design and moving bodies create. At the back of the stage hangs a thick rope noose. Pite comments wryly on the gauge of the rope fibres as she slips it over her head. The noose-dance or death-dance that follows is testimony to the depth of her movement artistry. Performed within the constraints of the noose around her neck and danced within a still spotlight, Pite becomes the weird white swan of contemporary dance.

And did you see how the noose, rising and rippling twenty feet up into the rigging, becomes an extension of her spine? That’s when I got hooked on construing Pite’s vocabulary as something quite new because she is uniquely sensitized to the life inside her vertebral column. Even in part one, “Farther Out”, she moves through her ideas spine first. It’s a pure kind of dance that circumvents, so refreshingly, the shackles of the thinking brain and its need to locate or look for meaning.

I must confess, Imogen, that I missed the element of the rope in relation to her spine. I did notice that my attention was remarkably focussed during that solo. The scene bears no clichés; it is not predictable, melodramatic or sentimental. Pite achieves the intended metaphor with simplicity, minimalism and a touch of irony in the moving image.

I found the remainder of part two, “Field:Fiction”, to be somewhat impervious to the kind of gut responses that either make or break my commitment to stay the course with the performers in any given work. Although I was planning to make notes during the show, my brain is short circuited by the soundtrack, and a multitude of de-constructed elements cleverly crafted by Pite, which build up to an impasto of frustration. It echoes my own frustration, accumulating with each new idea, which is barely established before it is chucked away like a piece of fresh cake on a paper plate. The weight bearing nature of Pite’s earnest and ominous commentary is quite undermined by the disposable surplus of thoughts served with every scenario. In selected passages of writing by Annie Dillard, Caulfield ruthlessly expounds the virtue of killing our most cherished creations, and I wonder, then, if Pite is attempting to demolish the work she has made while we watch it.

Now thoroughly de-constructed and disheveled, I land back in my body with a thud at a recollection of the pen and note cards in my handbag on which I have written nothing at all after intermission. I cannot even locate these two objects as my fingers rummage in darkness through the tiny purse I brought to carry them in. I gape at you, Mari, but you are avidly filling your pages by the minute!

I was trying to reckon with the field of soldiers &

Aha! The Kaiser’s Weebils, please explain.

In part two, the typewriter is gone and instead the stage is filled with a field of miniature metallic-looking soldiers staring out at the audience. Each soldier represents another sentence or paragraph on the creator’s battlefield. The base of each soldier is wide and round, so these soldiers will never fall, never die; they dip and bob and roll and rebound over and over again. As Caulfield authoritatively narrates the Dillard text, exuding a calm, character image of royal beauty and power, Pite exhausts herself on the dancer’s battlefield, her athletic and near-frenzied movements strategically covering the entire stage this time, and reaching ever-increasing crescendos of frustration. At one point she breaks frame and, taking off the battle helmet, pretends to make an emotional appeal to the audience: “I can’t see with this helmet on. I can’t see out the sides. I can only see straight, straight, front.” Then Caulfield leaves her seat and glides trance-like amongst the soldiers. Her movements rely on isolations and emphasize specific parts of the body. Hands and wrists twist in their own separate dance. Upstage, the still-concentrated profile of Pite steals our attention, as she stands curved over a soldier carefully dropping snow-like flakes in the air. In this odd moment, a magic quality settles over the theatre and a sense of relief ripples through our consciousness. Queen Caulfield and Colonel Pite have at last put to rest the irrational images of the unconscious mind.

I, myself, came to again at the beginning of Caulfield’s closing solo. And if I had been struggling to locate my emotional response to this piece then I was clearly given my remedy in this beautiful closing moment.

Relief gives that satisfying sense of resolution, like the promise of equanimity, but sometimes wipes the slate so clean that we cannot remember whether our question was answered or not. I felt the settling of my twitching mind as the snowflakes slowly made their stage-lit fizz to the floor and the restlessness that plagued me throughout the duration of “Field: Fiction” was simply liquefied into sorrow.

In the end, I might concede that Pite’s disconcerting subterfuge of my conscious mind was her idea all along.

But, part one, “Farther Out”, did not confuse me. Pite’s instincts for art making, for the most part, ring true and they stand up to our “programmed” expectations. Her comfort level is obvious here in her uninhibited approach to excavating the creaky wedges of the strange subconscious. I marvelled at the prowess of Caulfield and Pite, technically impeccable in a cocktail of tap shoes, T & A routines, rubber monster heads and their even weirder vocabulary when prop-less and unmasked. The piece is filled with apt metaphors for coming to terms with the monster of creativity, and unfolds progressively with a veracity and physicality that is very satisfying.

The final scene in part one, that might have seemed essential to Pite, is where I think her leap of faith in the process went awry. Part of the problem might have been in the structure. We return, again and again, to a duet of sorts where Pite encounters her resistance to Caulfield’s Sci-fi “wild woman”, who endeavors to pull off the Plexiglass bubble that sits on Pite’s shoulders and insulates her mind from the fantastically irrational. Thus, when her lid finally pops, it seems imperative, compositionally, to follow with a scene that shows us what this fresh perspective would look like. But, somehow, we already comprehend the bliss of such long-sought liberation. Exaltation and transformation, portrayed literally, can lead the choreographer astray more often than not and modern dance has been blamed in the past for its transgressions into sentimentality. So, we are wondering, how do you approximate a closing backdrop of the universe stretched out to the strains of Schubert in an abstract way, without diminishing the power or clarity of what they suggest? Why try to explain the mystery, when we can already exalt in the delightfully weird process that Pite so trustingly lays bare for us in her quest?

And Crystal replies:

That last solo at the end of “Farther Out” is a question. Ironically it is, as Annie Dillard puts it “&the original key passage, the passage on which the rest was to hang, and from which you yourself drew the courage to begin.” My original plan for that solo was to dance it in the astronaut helmet, at the beginning of the piece. I wanted the image of a floaty, bubble-headed explorer to speak of the artist’s innocence, a childlike fascination for possibility, a sense of vulnerability and hope. Proportionally, I felt like a giant toddler in that helmet, further emphasizing the concept. This was my “original key passage” for “Farther Out”. But while working on that solo and wearing the helmet, my movement was extremely limited and I often became somewhat blinded by fog and dizziness from lack of good air circulation. Still, I clung to the idea for a really long time, despite the fact that I was creating a work that was largely about letting go of one’s ideas. Later, as the piece continued to develop, and it became clear that Cori would be absconding with my Plexiglass bubble at the work’s end, I came upon the very question that you asked, “What has changed for me, the explorer, the creator, in that moment?” The helmet insulates me from real experience, in much the same way as the blinding soldier helmet does in “Field: Fiction”: “I can’t see with this helmet on. I can’t see out the sides. I can only see straight, straight, front.” What is it then, to be released? Having struggled to create a work about struggling to create a work, I felt it was necessary to examine the artist’s reasons for creating anything in the first place — I wanted to speak about joy. And for me, dancing is the ultimate expression of joy. But joy is a tricky thing to express in the contemporary dance milieu. Allowing that solo in the piece was the biggest risk I took in the creation of Uncollected Work. My fear was that someone like you would say that I had “transgressed into sentimentality”.

But for me, it was important to take the risk. I didn’t want to axe that dance for the wrong reasons. Scared as I am of being called self-indulgent, I still stick by it. “How do you approximate a closing backdrop of the universe stretched out to the strains of Schubert in an abstract way, without diminishing the power or clarity of what they suggest?” Exactly. What does joy look like, in abstraction or otherwise? And does anyone want to see it?

As a viewer, there is a world of difference between the solo at the end of part one, “Farther Out”, that is danced to a Schubert symphony in front of a galaxy of stars and the scene at the end of part two, “Field:Fiction”, when Pite makes stillness the dance, while she stands in her soldier’s helmet dropping snowflakes from a closed fist. The former is a familiar face of modern dance attempting to communicate an inner state of joy; the latter is a theatrical movement image that actually becomes the state of relief.

But here’s what I’ve discovered in light of Crystal’s comments about her closing solo in “Farther Out”: in prying apart the effects of the music and backdrop I find that, in hindsight, the dancing itself was not sentimental at all. While contemporary choreography occasionally leans too heavily on the musical strength of great composers, it could be that in this instance, the luscious contribution of Schubert leans too heavily on modern dance.

If Kidd Pivot can continue to make us believe in the magic of one concentrated image, an image that simultaneously engages our focus, and lets it disperse like a fistful of snowflakes catching light, then they have surely captured and understand the essence of creative process! There are moments in the dance wherein the body images gain absolute primacy in the performance, and there are other times wherein the movement is almost secondary to the Dillard text, and as you say, Imogen, occasionally to the music as well. Overall, Uncollected Work is thoughtful, smart dance.

Tagged: Contemporary, Performance, BC