At the heart of Pluton (French for Pluto), a new production from Danse-Cité, the Agora de la danse and the 2e Porte à Gauche collective, is something quite unique. If the former planet Pluto is now an allegorical term for being ruled out, these are dance artists who are not okay with being forgotten about — they are speaking up.

The ace in the hole of this production is Artistic Director and dramaturge Katya Montaignac, tapping the pulse of this city’s ever-changing dance landscape. A generation of choreographers (Nicolas Cantin, Catherine Gaudet, Virginie Brunelle and Jean-Sébastien Lourdais) at the forefront of the contemporary scene was selected to meet five eloquent veteran dancers (Louise Bédard, Michèle Febvre, Ginette Laurin, Linda Rabin and Daniel Soulières). Together they’ve created a robust evening, delivering a pure portrait of this fertile dance community in a series of contemporary works imbued with washes of poetry, introspection and brash dramatic invention.

The overall affection and admiration for these performers runs deep. This kind of casting can be chancy, in the sense of relying on a performer’s name and cachet and making that more important than anything else. Happily, the depth of their knowledge and experience proves invaluable here in creating some memorable work. None indulge in self-consciousness or self-congratulation. And while a good segment of the audience, particularly those in their twenties and thirties, might never have even seen these wonderful artists throughout their varied performance careers, this was a revelatory not-to-be-missed season opener for all.

Cantin’s brand of contemporary reflection is spare, experimental in content, though never veering toward the sentimental. Cheese (the only titled piece on the program), which debuted in 2013, delivers with a quiet and masterful performance by Michèle Febvre. Using fragmented sound elements, like the use of an old-style cassette tape playing the recorded voice of a young woman whom we never see, as well as live text, which Febvre speaks and repeats, the looping monologue orients the spectators into an evolving narrative. Prompted by Cantin’s invitation, “Tell me about your life,” Febvre digs deep into her past in this explorative role, delivering nuanced line readings about her childhood in post-war France. Past is present, and present references the past. The small, contained gestures give room to Febvre’s masterful delivery of the script and her intimate and deeply felt performance.

In Gaudet’s work, Bédard’s initial whispers evolve into almost guttural moans. In this theatrical vehicle, she captures, in bold colours and some delicate strokes, the awakened rage and frustrated passions of a person slipping into a surreal wonderland, all the while surrounded by great emptiness. A simple greeting, like “Bonjour”, becomes an entire internal experience. A phrase like, “Ça me dérange quand tu me regardes,” becomes a searing indictment. Other times, Bédard more lightly recalls in the briefest of sentences little recollections of her past, from her early life in Drummondville, QC, to her love of dogs and cats. And when Gaudet leans hard on the excessive verbal menace in the performance, in the form of exaggerated, anguished facial tics and menacing intonations, there is substance in her pauses, glances, shifting movements and bits of text, and it’s the subtle increments that drew me in.

What’s railing inside this woman might be unknown, but what we overhear is a searing, private lament. Her character’s disturbed, dark, brooding mindset guides our consciousness into a space saturated with patchy history. The work is tense, furious, absorbing, full of trepidation and demands a performer able to move well beyond cliché. Bédard brings her powerhouse presence and delivers a piercing immediacy to the role.

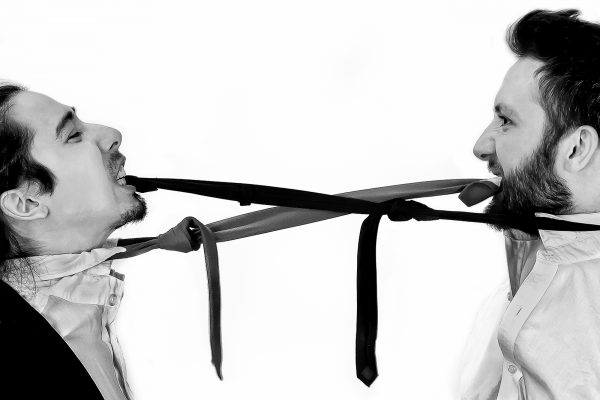

The duet created by Brunelle for Laurin and Soulières is a slight work, lifted by the performers’ sense of play and companionship. Passages include simple walks in unison and a sustained, repeated dance sequence that gently circles round one another. It’s a lovely moment when Laurin canters about Soulières and, with a small jump, swings herself around his body, adding a light inflection of her head with each spin. Unfortunately, the work sees the duo move more obviously into clumsy frustration or simply standing apart. The energy of the piece simply dissipates.

Rabin’s divine work with Lourdais enlivens the closing section. In this calm, essential somatic study, Rabin walks onstage, in jeans and a simple halter top, and we savour the rise and fall of her rib cage emanating from her breath. Whether squatting or rising, lying on her side, or slowly rolling over, she seems to build sequences at a molecular level. We see the gentle shifting of weight. At one point, as if on journey, she simply stands, looks out and then walks into the wings. An almost inaudible sound of a reed instrument fills the otherwise silent, empty space. Rabin returns soon after, and the music (by Tomas Furey) gradually gets louder. A remarkable thing then happens, and it’s something that I’ve rarely experienced in the theatre: the space seems to fall away. She (and we) could be anywhere. The music rises with a sound akin to a helicopter landing. Beyond all this fury is Rabin, eyes closed, her pelvis fluid and undulating. The motion builds with ease. The torso follows, and her arms rise and fall in the ebb and flow of the movement. The dance is ecstatic, intrinsically sensuous, and the performer sublime. This is one for the ages.

Tagged: Choreography, Contemporary, Modern, Performance, Montréal , QC