This article was first published in the Spring 2021 edition of the Current Society newsletter.

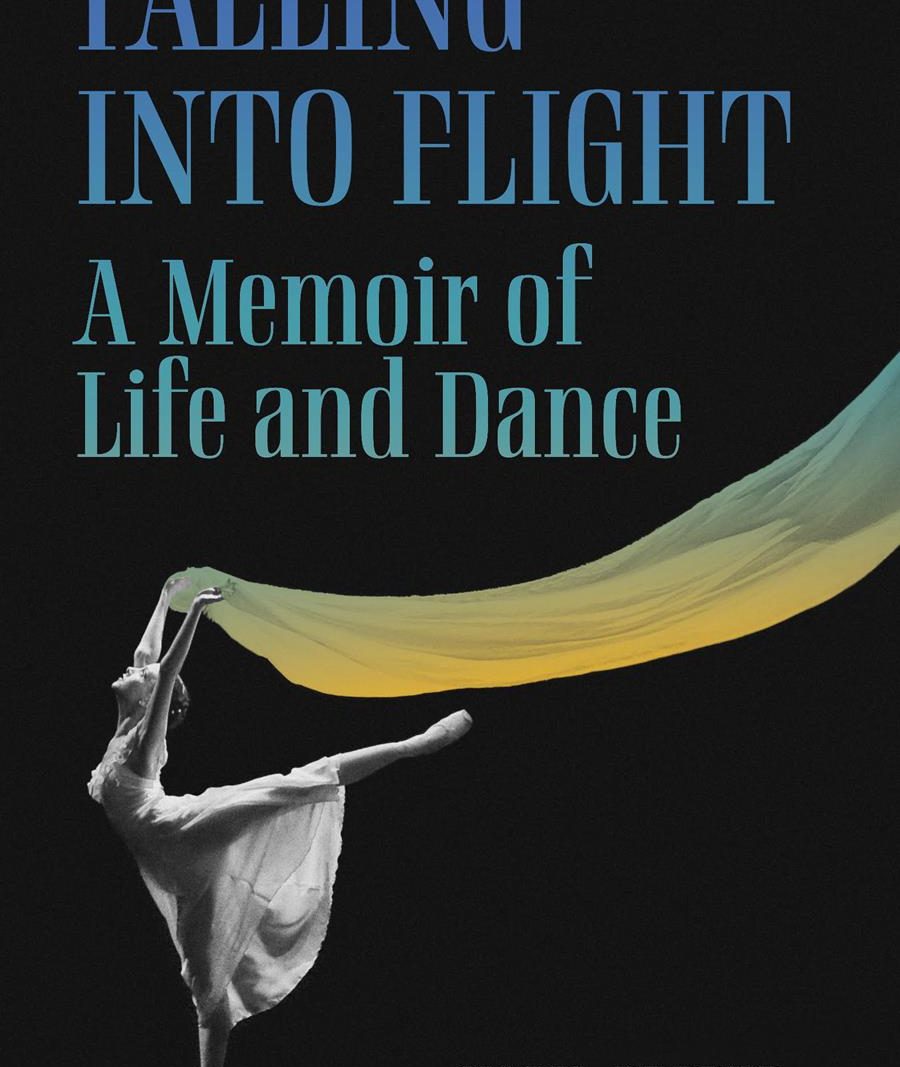

Describing the thorniness of recording dance (and one’s life) in writing, Kaija Pepper cites Arlene Croce’s concept of the afterimage – “the remembered dance” that remains in the mind’s eye after the curtain closes. In reading Falling Into Flight: A Memoir of Life and Dance, I can confidently say that books, despite their lasting tangibility, create afterimages too. Surprisingly for a fellow dance aficionado like myself, it was not Pepper’s life-giving encounters with dance that lingered after setting the book down but the more intimate interactions unfolding on the smaller domestic stage.

Pepper (née Susan Ann Kaija), a dance critic, historian and editor, grew up at 5211 Clarendon St. in Vancouver alongside three siblings and her Finnish father and Russian mother, Andy and Zina, both first-generation immigrants. Her relationship with each parent differed greatly. She fondly recounts the thrill of riding in her father’s Lafarge cement truck and his go-to dish of scrambled eggs and chopped wieners. Volatility characterized her mother’s presence. Zina’s tears and anger came quickly and without warning, creating what Pepper frequently refers to as a “river” of emotion running through their one-storey house with green siding.

The memoir that grows from these facts is a grippingly honest attempt to grapple with the traces parents leave within their children. Along the journey through her memories – often depicted in the form of dialogue with Dr. B, her therapist – Pepper brings her critic’s eye to bear on past events.

Her illustrations of her parents’ final moments (less than a year apart) were difficult to get through, not for lack of literary finesse; her vivid descriptions caused me to linger inside my own memories of watching for my grandfather’s final breath, “the intake coming after a long period when nothing happened and it seemed his lungs would never fill again. Then – one more breath – followed by that no-man’s land of breath and no-breath.” Capturing the dance inside that liminal space between life and death for both the departing and the observers at once.

A grippingly honest attempt to grapple with the traces parents leave within their children.

Kallee Lins

Pepper’s words so fully inhabit her childhood memories that I found myself wanting to skip ahead to the part of her story when dance becomes the central object, an anticipated relief from the complicated but often clearly painful exchanges between parent and child. Vignettes set inside the Graham-based modern dance classes of Linda Rabin, or the athletic choreographic experiments of Paula Ross, sparkle with all the energy and inspiration that was so abundant during Canada’s dance boom in the 1970s.

Descriptions of watching dance, “making that imaginative leap across the footlights into a heightened artistic reality,” felt all too sparse, but I will concede that this is appropriate. Fully immersing herself in dance became an escape from the challenges of early family life and its echoes into adulthood, and it becomes a precious escape for the reader as well.

The culmination of Pepper’s story is one in which her self-actualization entwines with her maturing dance criticism practice. After a handful of years in England, Pepper returned to Vancouver as a single mother, determined not to repeat the same patterns of emotional unavailability she witnessed in her childhood. In this period, she began her inaugural column for Dance International magazine, entrenching her status as a dance expert in Vancouver, across the country and beyond.

Flashing forward to 2011, Pepper describes herself sitting in the Queen Elizabeth Theatre watching a Ballet BC mixed program featuring the Finnish choreographer Jorma Elo and set to Sibelius, her father’s preferred composer (whom he often appreciated alongside a glass of whiskey). Here we witness Susan Ann Kaija colliding with Kaija Pepper, life and art merging into a unified whole.

Tagged: