Vancouverites had to wait until mid-November for the ballet season to open this year, when Ballet British Columbia premiered artistic director John Alleyne’s “Scheherazade”. The mixed bill also featured work by two other Canadian artistic directors: the National Ballet of Canada’s James Kudelka was represented with “There, below” and the new leader of Alberta Ballet, Jean Grand-Maître, by “The Winter Room”. Alleyne’s new work was, of course, the most eagerly anticipated.

The original Ballets Russes production, which premiered in Paris in 1910, was by all accounts a total theatre experience. The great impresario Serge Diaghilev put together a crack team for his “Schéhérazade”, which was based on The Arabian Nights, ancient tales of adventure and love that include the well-known stories of Ali Baba and Sinbad the Sailor. The choreography was by Mikhail Fokine, set and costumes were by Léon Bakst, and the now legendary Vaslav Nijinsky was the Favourite Slave. There was controversy over the use of Rimsky-Korsakov’s symphonic suite, “Schéhérazade”: Fokine used only parts of it, and completely ignored the storyline devised by the composer. While Rimsky-Korsakov had died two years earlier, and his widow finally gave permission for Fokine to use the score, Rimsky-Korsakov’s attitude to dancers appropriating music for their own ends was known to be disapproving. He once wrote about Isadora Duncan: “How vexed I should be if I learned that Miss Duncan danced and mimed to my ‘Schéhérazade’.”

But enough background; what was Alleyne’s take on the “exotic” Arabian tale? Very cerebral and very ambitious – cramming not only the story of “Scheherazade” into the hour-long ballet, but also three of her tales. His prologue, to a commissioned score by Michael Bushnell, tells the story of a Prince who witnesses the infidelity of his two wives. He slays them, and vows to put to death each morning the woman he has wed the previous day. Scheherazade, however, plans to tell the Prince an incomplete story each night, hoping his curiosity to hear the ending will postpone her own death.

Alleyne progresses to tell three tales to the same Rimsky-Korsakov score that Fokine used. The stories are impossible to follow, with their Slaves and Genies, love and betrayal. Part of the problem is that the ten dancers each perform more than one role – some up to four. Kim Nielsen’s costumes don’t help differentiate who’s who, either; the women wear similar harem-type tops and pants, while the men are bare-chested in pants. The colours are dark or muted. It’s difficult to tell a Genie from a Slave, a Woman from a Wife. Emily Molnar as the commanding Scheherazade and Jones Henry as a surprisingly sensitive Prince (given his penchant for killing wives) provide a welcome continuity. While Simone Orlando, Andrea Hodge, Justin Peck, James Russell Toth, Chengxin Wei, Sandrine Cassini, Nicholas Gede-Lange and Kristen Dennis come and go in a bewildering multiplicity of storylines, Molnar and Henry remain consistently Scheherazade and the Prince. Their smooth duets are compelling, though oddly old-fashioned with Henry often busy facilitating the performance of the ballerina.

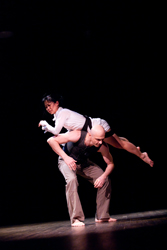

The fascinatingly awkward, perversely non-sensual movement that Alleyne has created for the women is a great experiment in how to go against expectation. Fokine’s Arabian ballet was all undulating spines and sexy languor. Alleyne, however, despite the romantic story and soaring, swirling music, motivates his choreography with an idea. That idea has to do with the apparent necessity to create original movement: the flat backs and prominent buttocks; the firm, flexed foot that abruptly ends the flow of most of the gorgeously extended legs; the jagged, bent legs that keep bodies apart. The angular shapes make it difficult for the men to carry the women, but watching them accomplish this feat was intellectually very satisfying. It was like discovering the most difficult way to do something – and the dancers were superb.

The disconnected feeling of the ballet arose in large part from Alleyne’s refusal to submit to the overwhelming, romantic music (which was recorded). It’s a legitimate strategy: dance doesn’t have to follow music and Rimsky-Korsakov isn’t here to complain. But the tone of the movement is so hard-core and anti-romantic that it is hard to understand the choice of music. Bushnell’s prologue, as sparse and glittering as the dance, could perhaps have been extended to the whole ballet.

The prologue was, in fact, quite brilliant. From the stark cream and black backdrop, with understated movement and music that bristle with tension, the ballet starts off redolent with portents of deep psychological secrets about to be revealed. Nielsen’s set is comprised of luxurious fabrics that hang, fall and disappear into the flies. With Pierre Lavoie’s lighting, the atmosphere is suggested rather than indulged. On opening night, there were some problems with the flow of the material – it seemed slow, and attention was drawn to the necessary wires. It was better the second night, but the moving sculpture of the fabric, though beautiful, still didn’t seem fully integrated into the action.

The second half of the evening began with strong performances by Acacia Schachte and Edmond Kilpatrick in Grand-Maître’s “The Winter Room”. The duet was created on an earlier incarnation of the company in 1995, and has been seen several times. This pure dance poem is succinct, clear and evocative. It’s great to have in the repertory, and to be able to revisit it every few years. Kudelka’s “There, below” was created on Ohio’s BalletMet in 1989. It is more traditional in the way it presents dancers as heavenly beings of grace and gravity, and felt a little flat for the close of an evening. Yet the five couples seemed to enjoy the classical beauty of its choreography.

Tagged: Ballet, Contemporary, Performance, BC