Pierre-Paul Savoie was a pro. Nimble in mind and body, feisty and funny. I knew him initially (now more than 35 years ago) – when I was a budding dance writer and he was a student in Concordia University’s dance program. Then, afterwards, as someone who laboured in the dance field, building on momentum and surviving. In the mid-’80s there were rich waves of excitement for a new generation of dancemakers. Walking into a studio at the university’s Victoria School, where the dance department was housed at the time, you got a sense of people, individuals, sharing what they loved. Later, on the city’s stages, their risk-taking efforts inspired their viewers.

It was a time of questioning the scope of a dance piece, and the democratic diversity of bodies and movements were energizing and irrepressible, reinventing the dance. For Savoie and his cohort, the paths they chose broke down barriers. Their attitude had DIY cred. The creativity and the gestures were fuelled by the time — AIDS, post-punk and generational change were all in the air. It was a moment when all this activity was redefining our understanding of dance and what could be seen on our stages.

Right in the thick of that upheaval was Savoie. In early works alongside Jeff Hall was a duo that soared. In their collaborations, as Hall wrote in an impassioned Facebook post after Savoie’s passing, they played off of and enhanced one another: “[This] tall athletic, straight Anglophone male attracted on the improvised dance floor to this smallish, energetic, gay, indépendantiste, Quebec Nordiques-loving Gaspésien. Two people more different you would never have met, yet an intimate collaboration of differences would successfully inspire us on.”

Both were students at Concordia under Elizabeth Langley, the founder of the dance department. The stress was on creation rather than technique. Here were burgeoning artists who expressed the shock and exhilaration of the age. Langley tells me, “I was being flooded with all these Québécois guys. Pierre-Paul impressed me [with] his intent.” Savoie had experienced a horrific car crash in his teens in the Gaspé. His leg was broken in many places, and doctors fused metal bars into it. At the time, Langley would audition applicants to the program one by one. She remembers Savoie walking in and saying, “You might notice that I limp.” One leg was 1.5 inches shorter than the other. Instead of having him audition, Langley gave him a private class. “He didn’t look very healthy. His body was not centred, and his organs were compressed,” she says. Savoie told her that he was taking gymnastics and contact improvisation classes, but barefoot. She encouraged him to get a built-up shoe. “That was the beginning of our relationship.”

“I don’t think I would even be talking to you if it wasn’t for Pierre-Paul Savoie,” Hall confides. At Concordia, they’d be doing contact jams in Andrew de Lotbinière Harwood’s classes. “I just got drawn in by him. … I pushed him and he pushed me in those jams,” Hall says. “And we’d come out of that, and we thought we’d just did the best thing since sliced bread. I mean, we were so overwhelmed with how we performed, how we connected with each other.”

With their complementarity, they made the jump from students to professionals with ease, making a student project into a working piece, Duodénum (1986), based on their comic-book heroes. As I wrote in Hour magazine, “Their mad, and dangerously funny, sporting, boyish, absurdist Duodenum, where no scene lasted for no longer than two minutes, was a crowd-pleaser.” I referred to them in a review as the “Mutt and Jeff” of dance. That statement resonated with Hall. “There was just that oddball mix of the two of us, complete opposites, me tall, strong, him small, wiry, hyper-nervous. Pierre-Paul was always, I can almost say, insecure with his own creations, always looking for things,” he says. The duo had an unstoppable energy in their creative bond and a total confidence in working together, their physical prowess matched by their technical wizardry. Audiences could relate. These were guys we knew. At the core of their work, beyond the humour and physical interplay was a simple humanity.

Hall tells me that during their spirited 16-year collaborative working relationship, Savoie would motivate him: “Pierre-Paul was always driving himself, [and] the shows. He was always filling out the grants and getting us into these different gigs. And I was playing the reluctant warrior, always asking, ‘Where are we going?’ I wasn’t sure what was going on, but I eventually started saying yes more often than saying no to the things Pierre-Paul proposed.”

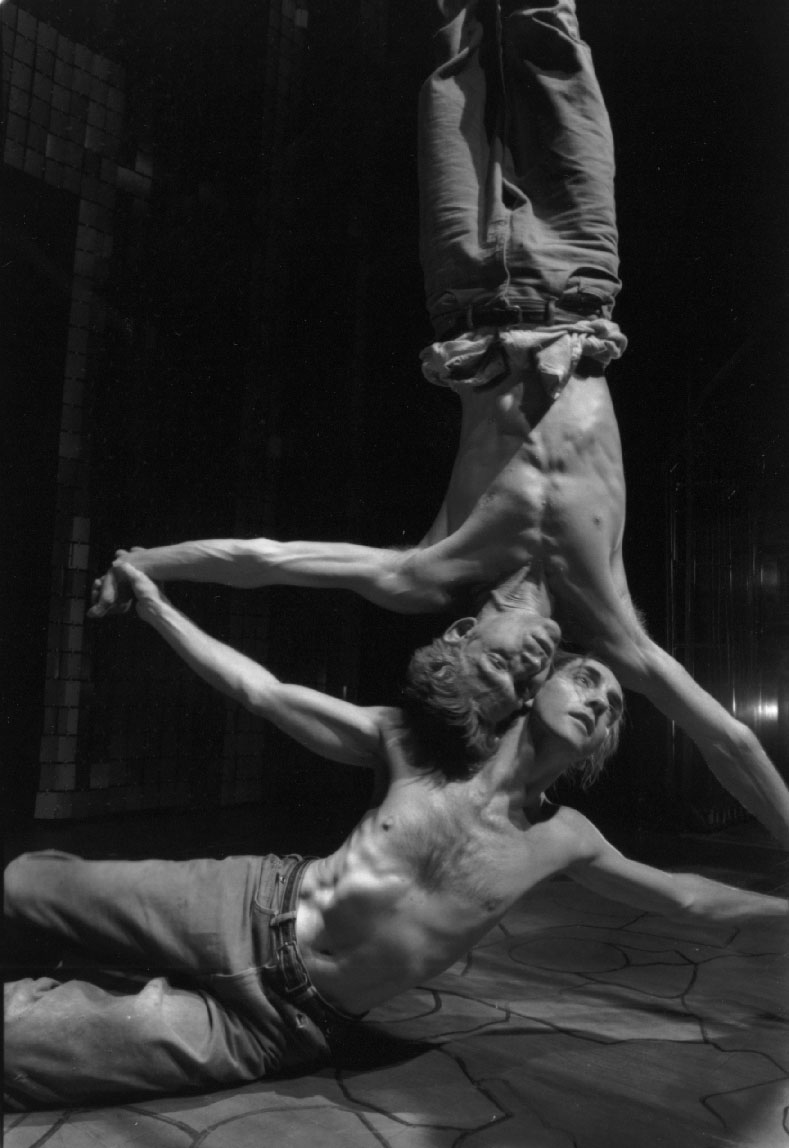

Their emotional bond was reinscribed in their explosive triumph Bagne (or prison cell), an exploration of relationships. As imagistic physical theatre, Bagne is a cinematic dreamscape, floating, shifting, violent and hopeful. The pair’s galvanizing presence lets you get lost. It’s a poetic moment in our country’s dance history.

Even when they parted ways creatively, they maintained a mutual love and respect. Hall says Savoie was “a good, astute businessman, relentlessly working hard. In the early days, he’d be typing programs into the wee hours.” Nobody can hustle like a dancer. “Even on his deathbed, he would open his eyes and say, ‘Let’s look at the archives,’ ” Hall remembers.

The canvasses Savoie subsequently created were imbued with high-tech affinities, though those qualities would be put aside in later more straight-ahead dance works. He would go on to many successes with his company, PPS Dance, and to professional heights, including as president for the Regroupement québecois de la danse from 1999 to 2004. All of this is on the public record.

To me, the message in Savoie’s work was that while we’re in this world, we have to strive for acceptance. I’ll always remember him as a warm soul, touching people, and as an artist onstage, graceful, incessant, immersed in the moment of performing.

Pierre-Paul Savoie died in Montreal, Jan. 31, 2021, at the age of 66.

Tagged: Contemporary, Uncategorized, QC