The seed was planted about a year ago when Michael Coghlan, associate professor in the department of music at York University in Toronto, pointed out in passing that Igor Stravinsky’s revolutionary composition Le Sacre du printemps was soon to reach its 100th anniversary. Perhaps, in celebration of the ballet’s centennial, he could perform, accompanied, the four-hand piano version of the score to a York Dance Ensemble (YDE) choreographic rendition of Le Sacre?

Met with enthusiasm by Professor Darcey Callison who rallied the rest of York’s Dance Department, Coghlan’s already ambitious idea blossomed into a three-day conference dedicated to celebrate, revisit and reflect upon The Rite of Spring. Hosted by York University’s Faculty of Fine Arts in conjunction with the Society of Dance History Scholars, the three-day academic event recently took place in Toronto. For the event, and in honour of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes’ multidisciplinary approach, conference chair Norma Sue Fisher-Stitt brought together a series of presenters from fields as varied and unexpected as somatics, the psychology of violence, 3-D motion capture and hip hop.

Anyone in attendance who doubted the relevance of celebrating the event a century on was reassured within the first few minutes of the opening keynote speech. In her address, Lynn Garafola, distinguished dance historian and author of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, made the very important point that, beyond its historical significance, The Rite of Spring remains a work-in-progress to this day. Indeed, with each new choreographic reconstruction (over 200 worldwide so far), we redefine as a culture what is understood as evil, what is understood as contemporary.

Following this insightful speech and over the course of the two days that followed, attendees from the national performing arts community mingled with scholars affiliated with such institutions as the Florida State University, The University of Western Michigan, the China University of Hong Kong and the Moscow Institute of Therapeutic Arts, among others.

The nineteen sessions included a noteworthy two-piano performance of Le Sacre du printemps by Christian Matijas Mecca (University of Michigan) and Ilya Blinov (Susquehanna University). The pair executed Stravinsky’s original rehearsal arrangement for the ballet side-by-side on the proscenium stage. Watching the pianists’ fine hands at work, on juxtaposed pianos and in the absence of choreography, intensified the familiar score’s experience tenfold.

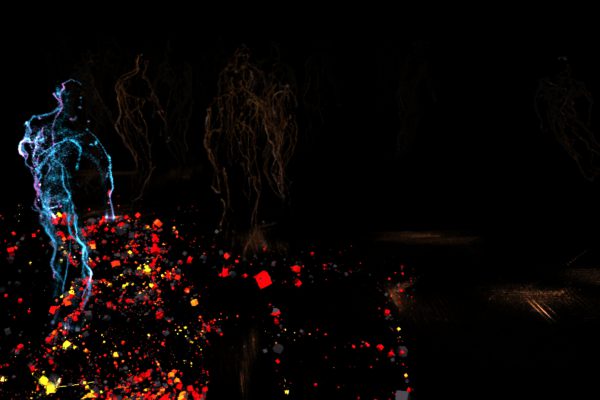

Another highlight presentation: filmmakers Martine Époque (UQAM) and Denis Poulin’s (Collège Montmorency) talk on the making of CODA, a short dance film set on a nine-minute excerpt from Stravinsky’s Sacre. For the fortunate few in attendance, the Québécois collaborators divulged the secrets of their experimental process in the creation of a dance film solely reliant on particles and motion-capture technology, completely devoid of the body’s presence.

Of course, the conference could not have focused on The Rite of Spring without addressing the riot at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées the night the Ballets Russes premiered their original Sacre in Paris. An entire paper session, Dance and Audience in the Age of the Ballets Russes was dedicated to the riot’s historical context, with an especially interesting presentation by Joannie Ing (PhD candidate, York) who, using content analysis of the period’s news clippings, attempted to piece together the mob mentality that fuelled the legendary uproar.

However, it is Rite Redux, a multi-act performance presented nightly in the Faire and Fecan Theatre and jointly delivered by York’s Departments of Dance and Music that constituted the weekend’s pièce de résistance. Simultaneously honouring Sacre’s centennial and the YDE’s 25th anniversary, the program was as substantial in quality as it was in quantity.

A welcome theme at a time when the winter weather seemed reluctant to leave, In Just Spring, performed by the YDE, opened the first act. Invested with collaborative complicity, the ensemble’s seventeen dancers and six musicians performed a mixture of structured improvisation and choreography directed by Holly Small, who drew inspiration from e.e. cummings’ 1920 poem In Just. Windy and mysterious at times, it was playful and dynamic at others, most admirably midway through when a three-minute adaption of Small’s Stupid Fabulous emerged seemingly out of nowhere. Here, the dancers moved like children in a playground, swinging, pretending to fight and making faces, their youthful energy a metaphor for the vibrant potential inherent i the season.

The breeze blew into the night’s second offering, Syrinx, a hauntingly beautiful flute performance of Claude Debussy’s 1913 composition, played by Kim Chow-Morris (Ryerson). It was followed by Le Sacre Bleu!, Susan Cash’s ode to Igor Stravinsky’s strength of character as a man. In a series of colourful, humorous tableaus (danced by York graduates Nicole Rose Bond, Irvin Chow, Brittany Duggan and Sky Fairchild-Waller), Cash choreographically riffs on a selection of the composer’s scores. Much in the manner of Stravinsky, Cash takes compositional risks and experiments with dissonance in this work. By juxtaposing scenes in an inorganic fashion, she is seemingly not seeking her peers’ praise so much as the integrity of her own expressive pleasure. Three 1913 Erik Satie and Claude Debussy compositions were played on the grand piano by York professor and acclaimed pianist Christina Petrowska Quilico to conclude the first act.

Following the intermission came York’s greatly anticipated own Rite of Spring, co-choreographed by Professors Carol Anderson, Darcey Callison and Holly Small. Performed by the YDE and accompanied by the four-hand piano rendition of the score, the multidisciplinary production had epic proportions. The choreography, multi-layered and spatially intricate, most often stayed rhythmically obedient to the score’s complexity. Many references were made to Nijinsky’s original choreography: internally rotated stances; deer-like and exaggerated trembling; bipedal jump landings and angular poses seen in profile are a few examples. Because the choreographers divided the score in sections and tackled those independently, the overall result could have been inconsistent. Instead, it was astonishingly cohesive and well integrated. Aesthetically, this new Rite is classical and polished; the choreographers capitalizing on the large number of dancers available to them to create powerful, dynamic dancing.

The plot from the original ballet was loosely followed: we recognize the maidens and a chosen one is sacrificed in the end. It is the setting that is new to this version of Sacre: the action unfolds in the woods of Northern Ontario. To support this Canadian essence, paintings of Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven were fragmented and projected on the cyclorama and wings. The strategy was successful depending on one’s vantage point in the audience. Seen from the orchestra level at the far back, William Mackwood’s projection and lighting designs majestically framed and efficiently enhanced Rite Redux’ dramatic content. Julia Tribes’ extensively researched costume designs, in which lumberjack plaid played a central role (the original costumes were used as reference, and Tribes progressively morphed the Russian pagan costumes into a Canadian-flavoured version. The sticks (long twigs), used in Rite Redux – referred to as “life branches” – were conserved from the original version) were just as compelling and perhaps more universally effective.

On May 29th 2013, Le Sacre du printemps will officially be 100 years old. Only time will tell whether Diaghilev, Nijinsky and Stravinsky’s ballet will inspire a new century’s choreographers to the extent it galvanized those of the last. But in light of the enthusiasm shared over the course of what was internally referred to as “the Sacre conference,” it is fair to say that Le Sacre du printemps will remain a work-in-progress for a long time to come.

Tagged: Conference, Contemporary, Discourse, Performance, ON , Toronto