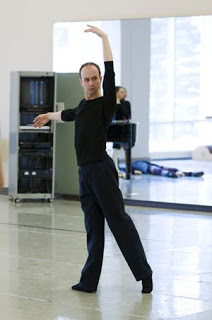

Peter Quanz is currently in rehearsal for his new ballet In Colour, with a score by composer Anton Lubchenko.

The studios of The National Ballet of Canada are a beehive of activity with the full company rehearsing works by Peter Quanz, Sabrina Matthews and Crystal Pite for the Innovation program, March 4th through 8th in Toronto. Quanz’s involvement began in discussions with Artistic Director Karen Kain after his premiere for the company’s Choreographic Workshop in September 2006. He explains:

The premise of this whole project is that we’ve each been given the same budget, and we can choose how to use that budget according to what we’d like to do for our own ballets.

While I was in Russia working with the Kirov Ballet I was introduced to a young Russian composer. His name is Anton Lubchenko. When I met him he was twenty-two, and he was sent to my studio by the Secretary of the theatre, Marta Petrovna. She’s decorated by Putin – so quite a powerful secretary. She sent me this composer partly at her thought and partly at the inspiration of former dancer-ballet mistress Elena Tchernichova, who has been a mentor and coach of mine.

They both felt a young composer should be paired up with a young choreographer – that the choreographer would develop by having access to new music and the composer would develop by being challenged with having to work with dance rhythms and a more theatrical sense of music than would be done in the concert hall.

I think this has been a very fruitful collaboration for the two of us. This is the second project that we’re working on but the first one to hit completion. We’ve been developing a full-length ballet, an original two-act work that is still in process. Timelines in Russia are strange things, so that’s why it hasn’t been up yet, but we’re working on it, and when I realized that project was going to take more time to develop, I thought, now that I have money from The National Ballet and I can commission the music, it makes sense to continue this collaboration with Anton, in order to give him experience working with me, give him his North American debut and also bring something of my experience in Russia to a Canadian audience.

Part of the reason it has taken so much time is that Anton doesn’t speak English, or he’s learning for this project but he doesn’t speak much, and I’ve had to learn Russian from my first day there, and so our communication is sometimes slow. But in doing so, it’s really forced us to listen to each other, to spend time doing silly things, or walking around the city or just getting to know each other as people, which has greatly influenced the choreography. I can see in the music the parts that he would enjoy playing on the piano. I can visualize how he would hold his body as he’s playing, and that in turn is going to shape some of my movement.

What is his way of composing – does he improvise? How does he share his music with you?

Well, he does several things. I mean there’s what he considers the serious music and what he considers his music for fun. Together with Elena, we would sit in her apartment, with the kettle always on the boil and eating cookies and just having a wonderful time. Eventually she bought a piano and had it hauled up to her fourth-floor apartment so that he could play for us. So now there’s this baby grand, well mid-sized grand piano, and it’s just for him. And we would spend all night every night.

He would play different types of music – sometimes Tchaikovsky, sometimes Stravinsky, sometimes Schubert. He’d give us concerts every night, and then he would launch into these twenty-minute jazz like sessions where he’d kind of bash through all kinds of different well known popular classical pieces and rearrange them slightly and make musical jokes. That’s the type of improvisation he does. These sessions would last all night and Elena would be fretting that the poor neighbours couldn’t sleep, and we’d get the odd shouts from the courtyard, but it’s music, it’s beautiful.

But in terms of his actual composition, he says he doesn’t sit down to write music. He hears it in his head and then sits down and writes it out. I remember very clearly when we were talking about the first theme for this ballet, which was the theme that we’re using for the very first section, the white section. It’s kind of an ostinato that is on the strings and it has other lines going through. He played one thing for us first, and it wasn’t quite what I was looking for, so I asked him to make a few changes.

He sat there maybe three minutes staring off into space, and then he got up to the piano and played the first theme exactly as he has written it. He went on to tell us what theme would come afterwards, how it would develop. In those three minutes he didn’t only come up with a new theme, he could see the entire structure of the ballet. And he could race through it, forwards, backwards, any given speed – it was like a three-dimensional object that he could walk through. The thought process and the way that it just flowed out of him was the most divine expression I’ve ever seen.

The National Ballet is understandably very concerned about the amount of rehearsal time that we have for these ballets. Three new ballets is a lot. To have three demanding choreographers running around, all using the same people, and trying to use the same resources is a challenge. And so even though Karen Kain wanted me to make a large classical ballet, she wanted me to do it on a minimum amount of rehearsal time, which is a huge challenge.

I thought if I am going to deliver that type of ballet, which I like to do and I’m good at and I enjoy, I should probably make a ballet that I can break into sections, where I can rehearse smaller groups of people. In my mind it was a theme and variations type work. When I mentioned that to Anton, he said, “Oh, no, theme and variation is horrible. You cannot do theme and variation in the year 2008. It does not work, no way. I write symphony.”

It’s one of those things where you can’t argue. It’s in two movements, but it’s called symphony in nine variations. When I went to break down what I was doing I realized that I didn’t always follow his breakdown of variations. Some of that differed, but that’s okay, I’m musical, too, and I can work within his structure. There have been some huge screaming matches, and also there have been slammed doors, Russian drama, but there’s also a real dedication to each other.

It was the three of us living together for more than a month several different times. He had his residence from the Conservatory, but it was far away and it was in the summer when the bridges over the Neva are raised at night so he couldn’t get home. It was three of us in an apartment all the time. It leads to some very high emotions, but one of the things that I’ve been working on is being more emotional in my choreography. I’m very clear on structure, but I need to show that I can also be more human, and perhaps this allowed me to open up that way a bit more. His music has provided me a wonderful vehicle and challenge.

In this process there have been points where I’ve had an idea where this project is going movement-wise before hearing the music, and when I heard the music, they fit. I don’t know why or how that could be, but it was like we were given the same information. I don’t want to turn that into too much of a mystical comment, but I believe there’s some kind of force behind it.~

For an introduction to Anton Lubchenko, his music and the city of St. Petersburg circa 2006, see April Man by filmmaker Dmitriy Lavrinenko:

www.dimalavr.com/en/ChelovekAprelya.html

Tagged: Ballet, Choreography, ON , Toronto