I’ve always felt like I didn’t quite fit into the box labelled “Indigenous dance artist,” even if I put myself in there. I resist the label, but at the same time, I feel a responsibility towards it. When applying for funding, “Indigenous” is a handy adjective to have in my tool box to describe myself. It also comes in handy with networking and helping other “Indigenous dance artists” to prioritize their peers. When working outside of Canada, however, “Indigenous” is the only descriptor I’ve been allowed to use, with “dance artist” cut out entirely. In those cases, the adjective was used to exoticize me and rug-sweep my education and accomplishments in favour of celebrating the people who “gave” me the opportunity to work in Europe.

The pros and cons of leaving that label in versus taking it out often end up balancing equally, but also precariously. When do I want my work to reflect on the community crammed like sardines into this box? When do I want to climb out of the box and take a breath for the sake of myself, my peers or my work?

I’ve been pondering what “Indigenous” means in the context of “dance artist” and what “Indigenous dance artist” means in the context of, well, “dance artist.” Perhaps these definitions are not static but ever-changing in their spatial, temporal and cultural contexts. To gain some understanding, I asked three artists from three generations of dancemaking to write about how the intersections of their identities might inform, beautify or complicate their relationships to Indigeneity, dance and the term “Indigenous dance artist.” Rayn Cook-Thomas, Ange Loft and Byron Chief-Moon have collectively curated a dance-focused journey through time, space and sub/cultures. — Amy Hull, guest editor.

***

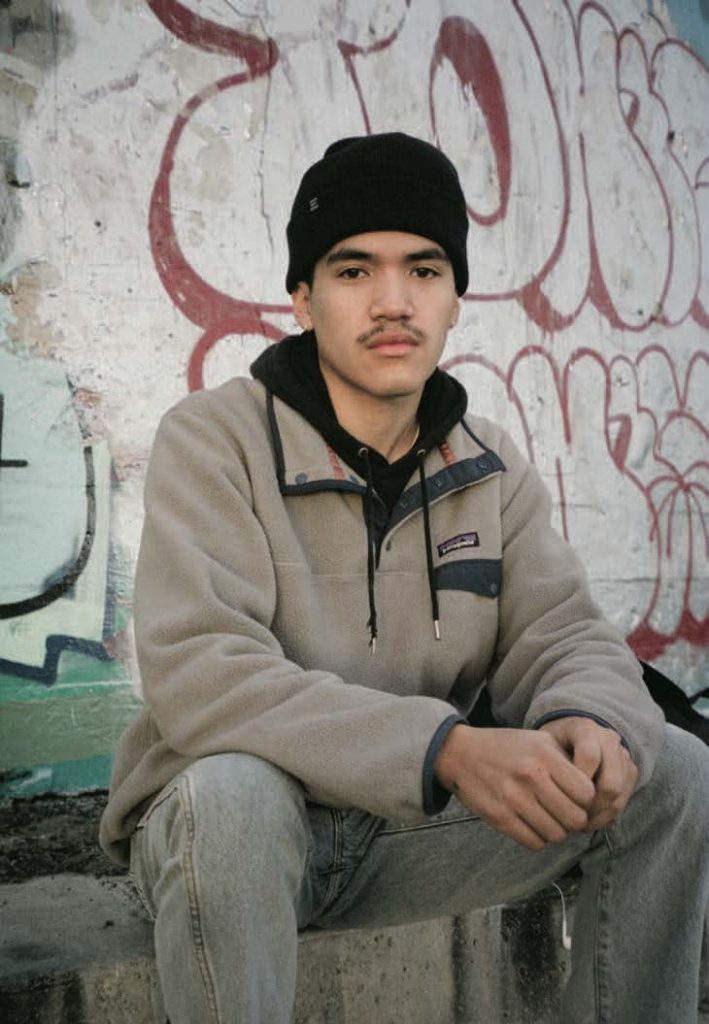

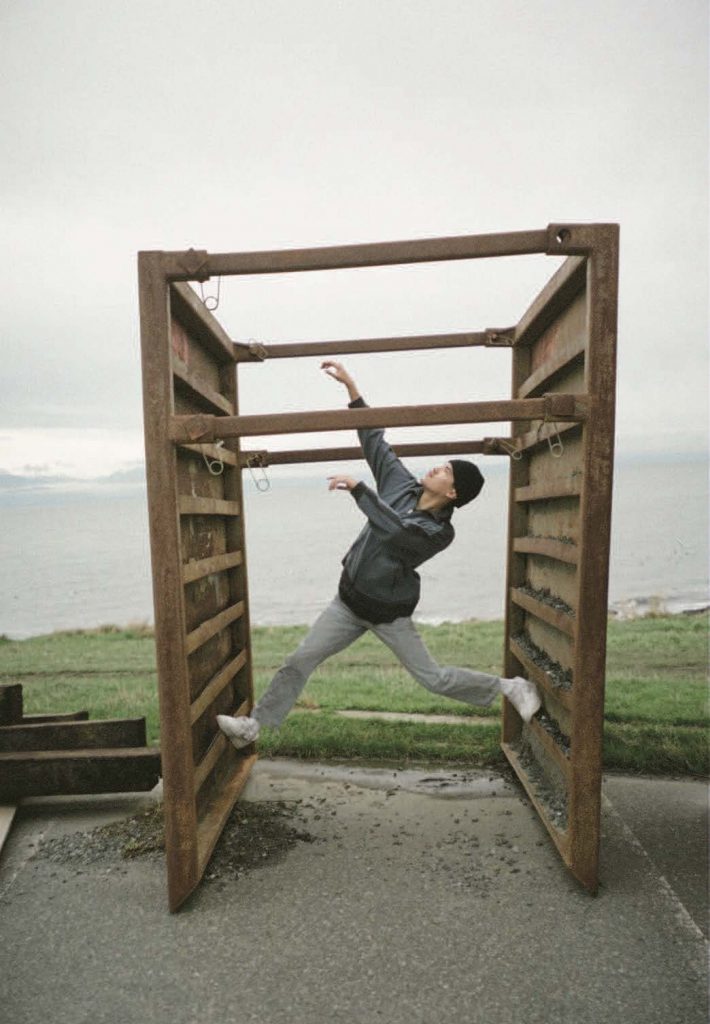

Rayn Cook-Thomas

My largest artistic influence is from my people, a coastal First Nation known as the Kwakwaka’wakw people in so-called British Columbia. What is paramount in the discussion of Indigenous dance, and sometimes misunderstood, is that my people were and are highly theatrical. When I step into our big houses, known as the gukwdzi, I can sense the rich history vibrating in the cedar walls; I am invigorated when the drummers call the drum to life; my attention is caught when the dancers sweep the floor with a sophisticated rhythm and spiritual demeanour; I am in the theatre when the dancers bring our world to life. The dance is not the art medium; the dancer is.

A choreographer once said to me, “I don’t think the theatre could ever be a decolonial space.” Yet what’s most powerful is that my people’s dances, songs, performances, traditions and expressions were not made to be “art,” like that of western theatre. They were made to be life. When I take this practice of Indigenous theatre and storytelling into my dance, it becomes the exciting challenge of breathing life into the stories I’m telling and the ways I’m moving.

My dance practice is Indigenous, as am I, as are my people.

Cook-Thomas

This influences my daily practices, which are contemporary dance and choreography in the York University dance program. A prime example is through mask work. In the Kwakwaka’wakw ceremony, large cedar masks are carved and used to tell stories and bring our supernatural worlds and animal kingdoms to life. The subtleties in the performance qualities are potent; using intricate, jerking head tilts and movements, delicate and thoughtful facings in relation to the audience and simple choreography across the floor takes the witnesses (audience) to a spiritual world only awoken in ceremony. The mask is treated as a living being, and in this sense, it comes with special protocols. To translate this work to a contemporary setting is daring but necessary. As I continue to incorporate Indigenous dance movement motifs into my contemporary choreography, it manifests in different ways: using a mask not as a prop but as an extension of the self and the body, which requires an acute attention to nuances and focus; acknowledging the audience as witnesses to the work, which asks for a respect for the story being told and how it will be received; using the dance space as a sacred space, which means that any entities, like masks, that the dancers work with are respected, upheld, brought to life in a good way and used with the required permissions needed from the community involved.

My dance practice is Indigenous, as am I, and as are my people. Our ceremonies do not bring witnesses to the supernatural world, but rather they bring the supernatural to them through complex protocols, a deep respect and a profound honouring of our elders in past, present and future. In the same way, I do not attempt to bring the environments I create through choreography to the studio, but I ask those environments to come to the studio with us, and to do this, I must keep in touch with my community, my identity, the land and my vivid cultural way of living.

Rayn Cook-Thomas is a contemporary dance artist based in Vancouver Island and currently training in Toronto.

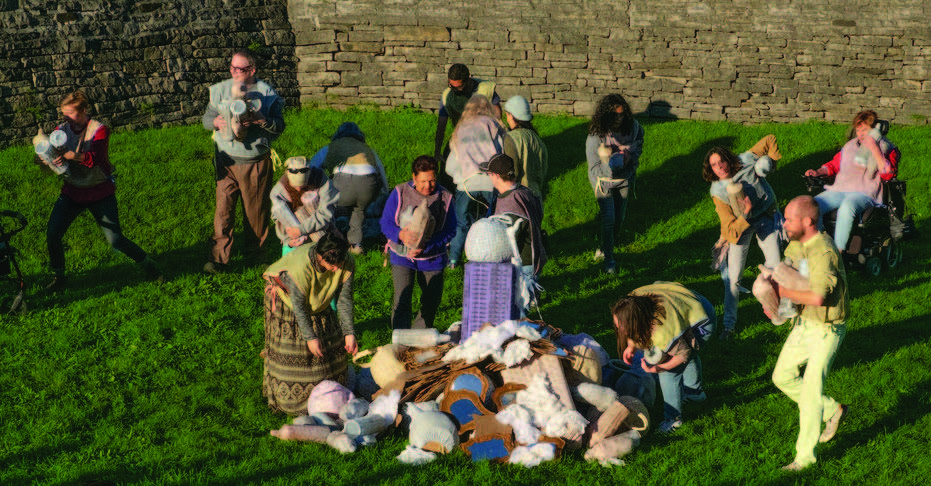

Ange Loft

I am someone who provides the basket for a dance experience.I take the first steps into dance, and then stop. I’m not necessarily a choreographer; I tend to work with choreographers who can take that kind of work and then expand on it and work a little bit further from there. I provide the framework for an experience with the materials and try to bring the right people together. I think about all the dance projects that I’ve created, and half the time, I was just cooking. It’s about creating the right environment to make sure that everyone can participate in a good way and that they’re comfortable, and they’re fed, and they’re happy, and they’re ready to roll. I sometimes work through arts-based research; for example, identifying a type of movement you see in the environment and replicating it to make a gesture phrase: the quivering of leaves and the falling of branches. This is an approach to embodying natural elements. It’s not particularly Indigenous, but it’s informed by land-based observations and sense and working together and kind of jumping off of what the space wants you to talk about. Am I particularly intrigued by leaf movements? No, but it’s a jumping-off point for collaboration. This past year, I’ve started with stories around the Dish With One Spoon, using historical agreements as materials. I prefer to be a person that brings the content to choreographers. I dig up the history and tell them which waterway to sit at and to figure out the work from there.

What places have the energy you want to harness? There’s an energy that I really love that comes from having a loud sound system. I was raised in a time period when extreme noise was part of our sound world, in Montreal with speaker huggers and the bounce-back of a dance floor. You don’t need to move; the floor moves you. It’s the same kind of feeling you get if you were in a longhouse at a social and everybody’s dancing in the exact same vibe and you don’t even need to move because the floorboards move your feet. I think about that connection between what the space wants, what the beat wants and then what falls out of people when you smash them all together to do something collaboratively. It’s the questioning of what the space wants you to do, which I think is a pretty Indigenous approach to creation.

My own movement history is grounded in the extreme and experimental, from electronic dance to industrial and heavy music. I travelled the world with a rock band for many years, and I kind of really loved the relationship between the performer and the audience. There’s the capacity to move a whole audience when we have the amount of focus that we need. I used to spend a lot of time playing movement games with my audience: extending my arms really wide, keeping the focus and then walking blindly into an audience to see if I could part the seas. I would do things like walking backwards very slowly with a tambourine through an audience to see if people will move for me, engaging an audience with power experiments. I like the power aspect of being the only Indigenous person in the room and forcing my audience to literally move around me.

I think the more we, as Indigenous creators, force ourselves into situations that don’t require us to identify as Indigenous and into collaborations with whatever dance artists really strike our fancy, the more we will be reincorporated and purposefully chosen for our skill sets.

Loft

People often ask me to talk about water. And it’s funny; I’ve said no to a lot of offers and collaborations about water recently. Then I did a weeklong art intensive with all these Indigenous women artists to talk about water. And I realized, I do want to talk about water; I just don’t want to talk about it with non-Indigenous people. Maybe the dance world needs to have the same type of internal and external conversations. There are things we want to talk about between ourselves without anybody watching, and there are things that we could pull away from and maybe choose not to talk about with outsiders. We have to make time to be inspired by each other, find things that are truly exciting for us, then have the agency to decide if we want to extend the conversation to others. Do I want to show you this layer of Indigenous genius? I’ll only teach you if you do something exciting with it.

I am also waiting for the next posse of Indigenous artists who don’t have to put any markers on their work. I think the more we, as Indigenous creators, force ourselves into situations that don’t require us to identify as Indigenous and into collaborations with whatever dance artists really strike our fancy, the more we will be reincorporated and purposefully chosen for our skill sets. Follow the energy; hunt out moments of pure excitement, the shared points of joy and interest to begin your collaborations. Yes, as Indigenous creators, we might have a unique set of movement abilities, and yes, you can choose where you want to begin and who you want to share your capacity with.

Ange Loft is an interdisciplinary artist and the associate artistic director of Jumblies Theatre.

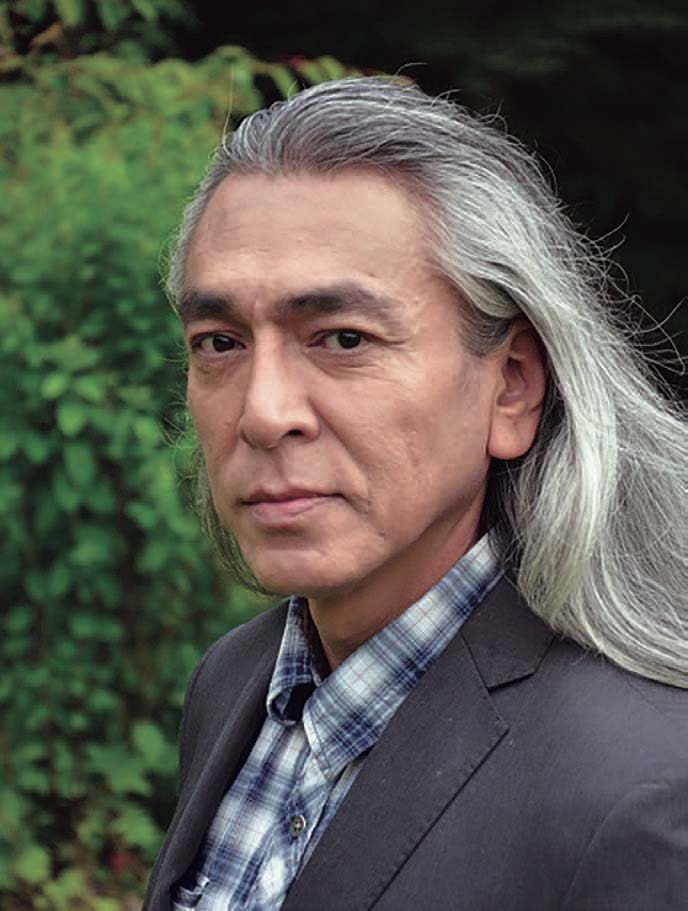

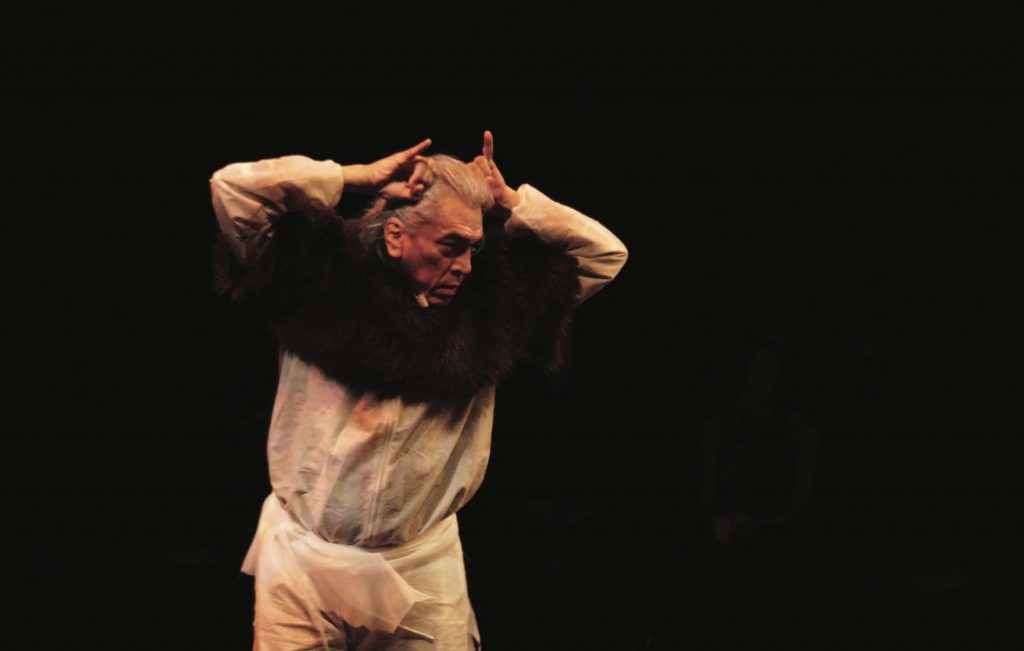

Byron Chief-Moon

Dancing has always been about the land, indigenous to my soul. I grew up in the vast Blackfoot Territory of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Montana. As a toddler, I was taught to respect traditions and religions, to honour one another and to respect the land and its gifts. My grandparents allowed me to experience sites sacred to the Niitsitapi (Real People). I have seen family members dance in our Sun Dance ceremonies, giving thanks to Apistotokii (Creator), God. Today, I see our younger generation continuing the dance of love and heritage. We are an ever-evolving society in an ever-dynamic world.

I live consistently in two worlds at the same time, dancing the stories of the land and interpreting dances through modern-day Indigenous dance bodies. Stories are affected by the narrative being imposed on the modern body of Indigenous dance. I dance with a national collective of like-minded individuals, bringing the dances of the land into modern theatres. As collective members, we bring our love of the land into the creation and rehearsal spaces. We share experiences by using more than the five senses we are told we have – we have so many more senses to explore with. Nature speaking to my senses allows the territory to intercommunicate while I dance. I grew up with family support to think outside of normal, to push the boundaries of society and listen to dance. When nature speaks, stop, listen and receive the creation of the land. I’ve been able to run on the land, walk in the forests, ride horseback on the Prairies and feel the beat of the land giving me the nourishment and energy to give myself over to nature and let it direct the dance within my mind, soul and body. At the same time, taking a standpoint from where I am currently and incorporating those feelings, images and words with all of my senses, and dancing like no one is looking.

I dance with a national collective of like-minded individuals, bringing the dances of the land into modern theatres.

Chief-Moon

I was on my own at a very early age, travelling throughout North America where most of my time was spent on the West Coast. I became involved in the performance arts by fluke. I had a job on a farm that was supplying horses to a movie set. My friend and I were “horse wranglers” for several days, three rainy windy southern Alberta days in late June. My job was to keep the horses close by and contained. When a pack of horses know they are not prey, they follow and it becomes a choreography – when you have trust in the dance director, you dance. I remember in grade school, when we would get home, Mom would be singing and welcoming us. We would join in, and soon we would be swaying to my mother’s voice, and our bodies would be floating around in space – freedom. My mother gave me confidence to respect the body, mind and soul, to pray and let the troubles fall aside.

Byron Chief-Moon is a multidisciplinary Indigenous artist.

Dance Media Group strengthens the dance sector through dialogue. Can you help us sustain national, accessible dance coverage? Your contribution supports writers, illustrators, photographers and dancers as they tell their own stories. Dance Media Group is a charitable non-profit organization publishing The Dance Current in print and online.

Tagged: