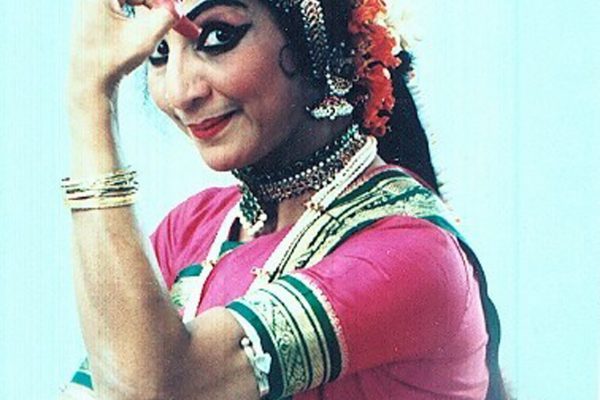

In an intimate venue in Bangalore, a small audience watches Menaka Thakkar during her company’s 2010 tour of India. The setting has none of the pomp and circumstance of larger performances Thakkar had delivered during her prolific decades-long career as a classical Indian dancer. No stage lights, not too much heavy gold jewelry, no intricate costuming – just the then 68-year-old Thakkar, alone, donning a black and red sari with dark kajal lining her eyes. But as she begins her solo, mesmerized whispers drift across the room. For those 40 minutes, Thakkar is Kunti, the mother of Pandavas, and her son Karna, the protagonist of the epic Mahabharata, switching between the roles seamlessly. Standing in the back of the room is Neena Jayarajan, one of Thakkar’s longtime students, former assistant teacher and assistant artistic director of the Menaka Thakkar Dance Company. “She just transported you to the place where she was,” she says. “We had forgotten she was a dancer first before she became the teacher, the choreographer and the institution builder.”

A master of bharatanatyam, odissi and kuchipudi, Thakkar rose to fame in her home country of India and can also be credited with establishing and developing these Indian classical dance forms in Canada. During her more than 50-year professional career, Thakkar opened Nrytakala, Canada’s first school of Indian dance; founded Menaka Thakkar Dance Company, the first Indian dance company to receive funding from the Canada Council for the Arts; earned an honorary Doctor of Letters from York University; and taught countless workshops at schools across the country. She’s been recognized for her influence on Canadian dance through numerous honours, including the 2012 Walter Carsen Prize for Excellence in the Performing Arts and the 2013 Governor General’s Performing Arts Award for Lifetime Artistic Achievement (Dance).

Thakkar “pioneered a professional dance form in Canada and gave it the foundation on which subsequent generations could build,” says Amy Bowring, executive and curatorial director at Dance Collection Danse. Thakkar’s death on Feb. 5 comes after years of nurturing and leading legions of performers within Indian classical dance and beyond.

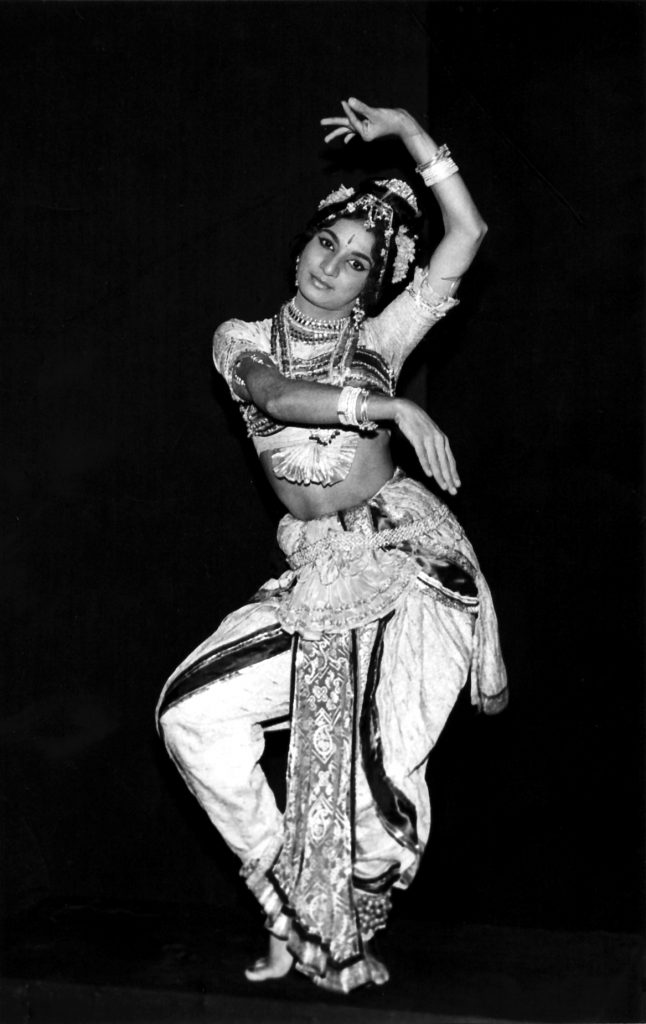

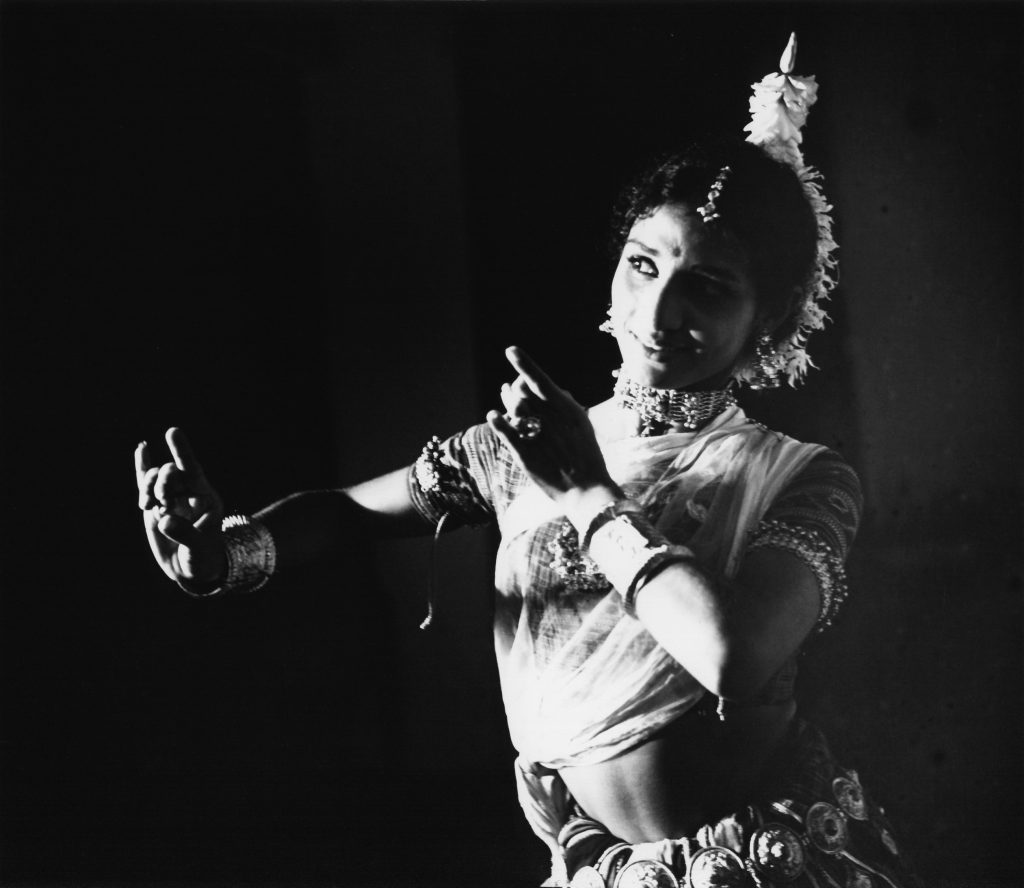

But before all of that, Thakkar was a dancer and destined to be one – in Sanskrit, Menaka means “celestial dancer.” She began her bharatanatyam training in Mumbai at the age of four with her older sister, Sudha. For an entire week, Thakkar practised the foundational first step of tatta-adavu, repeatedly stamping her foot against the ground in the aramandi position, eager for her sister to trust her with the next step. In her teens, she trained with the renowned Guru Nana Kasar before expanding her expertise to include odissi and kuchipudi in her 20s. At the time, learning multiple forms wasn’t common for fear of compromising one technique with another. However, Thakkar dispelled any and all hesitation with her mastery, twice receiving one of India’s highest honours, the Singar Mani Award: for bharatanatyam in 1968 and for odissi in 1970. “She was committed to doing each form with its utmost integrity,” says Nova Bhattacharya, founder of Nova Dance and Thakkar’s first Canadian student. “She just had this insatiable curiosity about every single form of dance.”

That same curiosity is what drew Thakkar to Canada in the first place. In 1972, she travelled to Toronto to visit her brother Rasesh, who was teaching economics at York University. She wanted to learn about western dance forms and find a way to share her own work. Thakkar came onto the Canadian dance scene during the modern dance boom in the 70s, just as university dance programs were first being established, says Bowring. This time saw the advent of experimental venues like 15 Dance Lab, an open space for dance that provided performing opportunities to everyone, including Thakkar. Through performances like these, Thakkar’s dances were, as Bhattacharya wrote in Dance Collection Danse’s magazine in 2006, “instantly recognized for their technical brilliance and graceful elegance.”

Considering she’d established herself as a sought-after performer in India as well as a rising talent in Canada, Thakkar had to make a decision. Ultimately, her choice to put down roots in Toronto in 1973 wasn’t because of the demand from western audiences. Rather, Thakkar felt a responsibility to fill the gap of artistic education for Indian communities living away from their ancestral homeland. “Canada was a new garden, where she was planting the seeds of all these dancers she was training, that she needed to keep watering to change the cultural landscape,” says Bhattacharya.

So in 1975, Thakkar opened Nrtyakala Academy of Indian Dance to educate a new generation of classical dancers. In 1978, she founded the Menaka Thakkar Dance Company to give them a way to share and tour their art around the world. Jayarajan’s first interaction with anything cultural was joining Thakkar’s school at age seven. “Even though my parents are first-generation immigrants, I was still very much disconnected with [my culture],” she says. “I learned everything in the dance classroom.” She recounts the vivid details Thakkar brought to the studio to help students draw on experiences they’d never lived through themselves. A move was never just technical; it was personal: Thakkar’s students were made to understand how butter used to be churned with a stone and a string, how heavy the apparatus was, how one would have to sit on the dirt floor while using it, under the glare of the hot sun.

“She would take the quietest, shyest, most introverted dancer and bring out these exuberant, dynamic parts of them onstage,” says Jayarajan. While Thakkar valued learning that catered to the individual, she still made sure no one ever felt like the odd one out. For each of her students’ arangetrams – solo debuts that mark a student’s graduation – she ensured the setup and conditions were the same. While modern arangetrams are known to be momentous and elaborate, with multiple costume and set changes, Thakkar kept things simple so no child felt hindered by financial barriers.

“It came from her idea of access and making her teaching accessible to anyone and everyone,” Jayarajan says. Thakkar felt that this access should extend to students across Canada, especially in isolated communities. Thakkar would “province hop” to conduct workshops, teaching children how to dance but also how to take pride in their heritage. “Unapologetically, she’d walk in anywhere with her sari on,” says Jayarajan. “She was five foot two and 100 pounds but stood like someone who was six foot five.… She wasn’t someone who was trying to blend in.”

Bhattacharya says Thakkar was always able to transcend borders of race and culture. She particularly recalls one performance in an artist studio in the York Quay building in the ’70s, where Thakkar was dancing a pushpanjali without a stage, surrounded by pottery wheels, for a largely white audience. “It was the most incongruous place to see a classical bharatanatyam performance, and yet she did it,” Bhattacharya says. “She would just sparkle when she danced.” Thakkar was known for preparing her western audiences with brief lecture demonstrations that explained the meaning behind the characters, hand gestures, rhythms and eye movements.

While she worked tirelessly to secure essential funding for Indian classical arts, Thakkar recognized that the art form itself could have more of an impact than written words. In 1985, she strategically invited members of the Ontario Arts Council and Canada Council for the Arts to Bhattacharya’s arangetram. “When the officer actually sees … how a community comes out to support something that has such cultural value,” says Bhattacharya, “that’s far more powerful than writing all those words on a grant application.”

But Thakkar didn’t stop at changing what was considered professional dance in Canada; she also pushed the boundaries of Indian classical dance. She consistently reinterpreted traditional works to take on feminist themes, like in her production of Sitayana that recounts the epic poem Ramayana from the goddess Sita’s point of view. She collaborated with a range of artists including Grant Strate, Faye Thomson, William Lau, Claudia Moore and Danny Grossman in productions like Land of Cards and Duality that synthesize and compare different cultural dance forms. “She didn’t [only] belong to the world of Indian dance,” says Bhattacharya. “She had an incredible impact on the dance scene in this country because of all these artists from different backgrounds who were also touched by her creative spirit.”

Yvonne Ng, artistic director of tiger princess dance projects, knew of Thakkar even before she immigrated to Canada from Singapore. While she only danced for Thakkar once, in 1993, the impact of working with her was enormous as an artist of colour and she continued to look up to Thakkar as a role model. “Every time I got to see her, I felt like she had a special little twinkle and smile that was just for me,” Ng says. “It hurts my heart that my time with her was short, but I think it’s how that time [was] spent that creates the path forward.”

Thakkar lived a life in service to her art. Jayarajan recalls Thakkar always telling people she was married to her dance and that her students were her children. She wanted everyone to know she was an artist, from the Uber driver to the ticket taker to the person serving her food. In the last few days of Thakkar’s struggle with Alzheimer’s, Jayarajan and a few other dancers played odissi music by her bedside, ringing ghungroo bells and filling the air with drum syllables. Thakkar hadn’t been fully responsive, but in that moment, her eyes shot open and she began to make noise. “Everything else was gone, but the dancer in her was strong as ever, even until the end,” Jayarajan says.

In that way, Bhattacharya says, the greatest tribute to Thakkar is to live a life dedicated to art. “I will accept being one of her seeds, whichever way the branches grow. There’s nothing that can ever separate me from the influence of an artist like Menaka.”

Menaka Thakkar died at a long-term care facility in Toronto on Feb. 5, at age 79.

Dance Media Group strengthens the dance sector through dialogue. Can you help us sustain national, accessible dance coverage? Your contribution supports writers, illustrators, photographers and dancers as they tell their own stories. Dance Media Group is a charitable non-profit organization publishing The Dance Current in print and online.

Tagged: