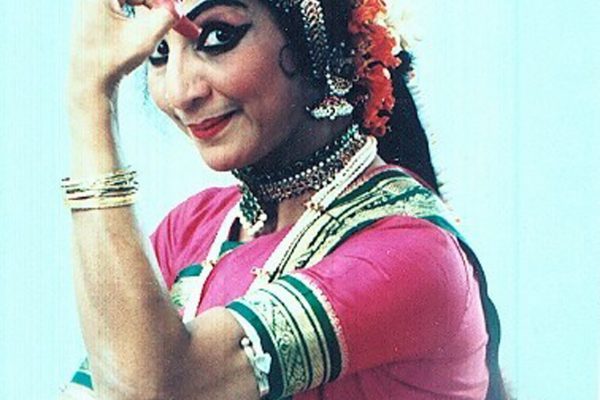

Menaka Thakkar of the Menaka Thakkar Dance Company and her sister Sudha Khandwani of Kalanidhi Fine Arts of Canada are co-producers of the upcoming International Dance Festival and Conference: Contemporary

Choreography in Indian Dance.

You are interested in questioning what is “contemporary” in Indian dance both in India and in Canada. This issue has long been at the centre of your work in various ways, through collaborative productions with western contemporary artists and through your own choreographic explorations, for example. What is the significance of asking this question today?

Menaka: It is true that during the period of my own development of ideas about new directions for Indian dance, I explored various different possibilities, and collaborated with several western contemporary choreographers and music composers. One of my contemporary creations of that period was nominated for the Dora Mavor Moore Award for new choreography. Working with these artists stimulated me as much as it raised a large number of basic and often troubling questions as to what exactly is the notion of “contemporary” as against the “traditional” dance and what are the most appropriate directions to develop contemporary choreography in Indian dance? Many of my collaborators shared my concerns and thinking about these issues. But then, there were others who expected a certain specific “look and feel” and “creative process” of a choreographic work to be recognized as “contemporary”, without considering that their own notions and definitions were so much a product of their own cultural history and the tensions which had characterized their own “traditional” and “modern”, “post modern” or “contemporary” art forms.

The terms, “contemporary” and “traditional” are at best elusive and become meaningful only when understood in the context of a tradition’s unique history and its present status. The terms do refer to and revolve around an essential spirit and perspective with which life is interpreted through art. But, the contemporary dance can not be homogeneous over all cultures even when it is fundamentally shaped by a common essential temper, for this underlying spirit itself will find its expression through diversely cultivated cultural symbols, dance vocabularies and theatrical conventions. Of course these too can be, and are indeed, challenged and reexamined. But this need not wipe out essential cultural diversity and impose a new conformity on all contemporary dance. All contemporary art, although bound by a common spirit of the age will still remain culturally differentiated in its manifestation. All these are valid on their own terms and stimulate very rewarding cultural experiences if one can be open to them.

There are a number of other interesting issues around the notions of “contemporary” and “traditional” which have arisen with different urgencies and different emphases in several related art forms, including visual art, music and literature. It will be clearly to the benefit of our art to think of some of these issues in a larger framework of diverse cultures and art forms that are both differentiated and interrelated at the same time. This is true not only for a deeper understanding of the historical development of modern or contemporary movements in European and North American art forms including dance, but even more true in dealing with the questions, concerns and tensions that underlie the contemporary movements in several Indian art forms including dance. In fact, for the Indian case, one can properly grasp the issues, rationale and the direction of development of contemporary dance only if they are examined in the context of a comprehensive modernizing process that started as a uniquely Indian response and has been at work for more than a century, covering in its sweep several fields of human activity and institutions and leaving its large impact, directly or indirectly, on the Indian psyche.

At another level, the concepts of time, space, human psyche and human body — along with the nature of forces that animate and energize it all — will come in for a reexamination and will affect the nature of contemporary dance in India. Movement of Time, in Indian perception, is not linear; it is cyclic. And thus “past” or “traditional” practices and concepts may become relevant to us and will often come back as “modern” or “contemporary”, such as the humanistic concept of art of the ancient Greeks which has come back to us in our times. Or the insight of modern physics that locates the origin of matter and material energies at those non-manifest levels of reality that are beyond our grasp by the normal sense perception. This hierarchical view of the existence of reality where each level is connected with different human cognitive faculties, which are in the process of evolution, is a strongly held philosophical and spiritual position in India. The traditional Indian systems of Yoga were intended to aid and accelerate this evolution in an individual so that connection could be established with the other levels of reality. A dancer who primarily explores physicality and functions through physical energy will therefore work with the system of physical Yoga (Hatha Yoga) whose postures, breathing and movement vocabulary connect with those subtle centres of physical energy. This realization has made (Hatha) yogic exploration of movements an integral part of the emerging contemporary Indian dance in the approach taken by several choreographers and interpreters. Here, an ancient tradition is seen to be an essential part of a contemporary dance movement.

I am aware that there are several other choreographers who too have explored this area, deeply thought about it and created their contemporary works often adopting different approaches. I now feel that the time has come when my company has to formally integrate our own history with the creative talents of all these other artists by creating and offering a formal space to generate discussions and understanding of alternative visions, and creative efforts. That is why I have jointly organized this event with Sudha. This will hopefully gather together other creative minds to discuss, analyze and showcase explorations in contemporary dance, and to create stability and continuity of effort in place of disjunctions and uncertainty of ad hoc efforts. If successfully stabilized and sustained, this will build new energies.

It seems that South Asian practitioners are among those at the forefront in critically examining the cultural forces of both tradition and innovation in artistic work. Do you agree? If so, why do you think this is the case?

Sudha: It is true that dance artists and dance scholars in both India and the Indian Diaspora around the world have remained very actively preoccupied with the issues of tradition, innovation, modernity, etc. In order to understand it fully, one has to consider the unique nature of the struggle for independence of the colonial India in the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries. This struggle was not limited to political independence from the British; it was a sweeping and integrated process of a total transformation of India’s society, political system, religious institutions, and artistic and cultural regeneration. The leaders were acutely aware of a dual concern to reclaim India’s unique identity and heritage while reforming and modernizing many of the social practices and institutions. Often the dual concerns seemed to find their simultaneous fulfillment in reviving the values and practices of the ancient past in their original pure forms, which often looked surprisingly modern or were easily reconcilable within the contemporary spirit. Thus many of the modern social, cultural, religious and other ideas and movements, often received from abroad, were “Indianized”. Thus socialism, feminism, the fight against colonialism, artistic practice, etc. embodied both the contemporary spirit and the “Indian” cultural worldview. The revival and reformation of Indian dance systems, which were part of this general process, were seen to be both the reclaiming of the tradition and its modernization at once. Thus the development of contemporary art forms often generates an ambiguous response of tension as well as a sense of organic growth of tradition aided by deep contemplation, not a rebellion. For example, contemporary artists like Chandralekha would go much deeper in the yogic and martial art tradition of India to understand the movements and process of energy generation and integrate that insight with the inner form of Indian dance, devoid of many outer superficialities, to create contemporary Indian dance.

When you describe your work, do you prefer the term Indian or South Asian?

Menaka: These labels serve different purposes and, in the right context, are useful. Otherwise they are too broad and ignore real regional, cultural and stylistic-technical differences. I use specific terms such as bharatanatyam or odissi or kathak for the styles I practice. To speak at the level of recognizable commonalities of various dance styles, I use “Indian”; that is broad enough for me. I find “South Asian” rather too broad and thus misleading, although it is commonly used in the UK, the USA and Canada.

Kalanidhi Fine Arts of Canada has been presenting festivals and conferences since 1993. How does this festival and conference event relate to its predecessor, the Kalanidhi International Dance Festival and Conference? What new initiatives are you introducing in this collaborative program?

Sudha: Kalanidhi’s mandate and vision particularly emphasize the promotion of contemporary works of Indian dance and facilitate the exploration of all its creative-aesthetic as well as intellectual-analytical issues. I organized, right at its inception, the first Kalanidhi International Dance Festival and Conference in February 1993 on the theme of contemporary dance in India under the title “New Directions in Indian Dance”. This premier undertaking was indeed not intended to minimize the importance of traditional dance, but to bring it in proper balance by dispelling the then-prevailing myth that all Indian dance was only its traditional form and that its repertoire reflected the sensibilities of bygone ages. Since then Kalanidhi organized a variety of such events revealing the range and beauty of both traditional and contemporary Indian dance, including the works and visions of young choreographers and performers born and raised in the Indian Diaspora around the world, where they necessarily straddle the two cultures.

In 2004 and 2006, I organized a two-part festival and conference, “A Century of Indian Dance” covering a period of the last 100 years, eight classical dance systems and seven different countries around the world. The intent was to witness and understand the recent evolution of Indian dance and the process of building and rebuilding of its traditions. Although a few choreographers from the Diaspora presented their contemporary works – representing an important branch of Indian dance-in-evolution during that vibrant period – a good deal of important exploration and new works which have been going on, particularly in the last thirty years or so, remained to be systematically presented. It is therefore natural, almost imperative, that the unfinished and constantly evolving story of that century be taken up and continued in the upcoming festival-conference activities of 2008/2009.

The major new initiative of this event is to place the pioneering role of the renowned choreographer, Chandralekha (who passed away on December 30th, 2006) in central focus and pay tribute to her for her contribution to the development of contemporary Indian dance. It is significant that Canada has had the distinction of having hosted her four times (I first invited her in 1993 to participate in Kalanidhi’s first festival). I then helped organize her two-week residency at the Toronto Dance Theatre, followed by a Canadian six-city tour of her company performing her then-latest work “Mahakala”. Before the tour, Chandralekha was also presented by the Harbourfront’s Movado Dance Series over six evenings.

Another initiative is to invite German dancer-choreographer Susanne Linke, who was very close to Chandralekha and sometimes provided critical feedback on her new works. Susanne will speak about Chandralekha’s contribution to contemporary dance, and also perform a piece of her own creation followed by another solo performance by her partner. In addition, the last work that Chandralekha had completed before she passed away will be performed by her dancers from India. Sadanand Menon, Chandralekha’s long-time associate and collaborator will give a complete idea of her life, work and views on dance, supported by excerpts of her works.

Who is your intended audience for the event and what can they expect from the experience?

Menaka: At one end, our intended audience will come from the practitioners of any Indian dance system: choreographers, teachers, students and the general audiences of Indian dance. More generally, most practitioners of all culturally diverse dance forms and their audiences should also be interested, because although the issues of contemporary dance and their approaches to creations of works will be presented in the specific context of Indian dance, most of them are going to be clearly relevant to these other dance cultures. Most generally, all these issues and the creative visions in the open global cultural scene of evolving dance will be of relevance to the Euro-centric and North American dance practitioners, both contemporary, ballet and contemporary-ballet. Some of the concerns reflected in the creations, performance practices and philosophical discourse will ultimately touch upon notions of contemporary aesthetics and sensibilities, in the context of differentiated cultural and social histories, political realities and rapidly evolving technological possibilities. All these factors will connect and bind not only different dance forms but various different art forms in general: music, theatre, visual arts, literature, etc. Our intended audience resides in those related areas too.

Do you see this event as a kind of continuation of Chandralekha’s legacy? If so, how? What is your personal connection to her and her work?

Menaka: Not in any direct way. Neither this event nor the works presented at this festival constitute a direct legacy of Chandralekha (except her own work which will be presented on January 24th); but it will be abundantly clear from the presentations at the conference that any serious thinking and creation of a work of Indian dance, or for that matter any dance, will involve the issues that she had been so passionately and deeply exploring and the directions that she had been pointing out for our serious consideration. It is particularly important to understand her views and gain an insight into her creative process for those of us who are asking perhaps the same questions that she asked and are struggling perhaps with the same issues of contemporary dance that she had deeply thought about. This is the most important legacy that she has left for us, all dancers of all genres.

As for her direct legacy, it is highly unfortunate that although of deep significance for the development of contemporary Indian dance, many of her works have not been seen widely; her own company does not exist anymore. An honest understanding and objective evaluation of her life and art are lacking. And now she has passed away, leaving a large body of some of the most radical and deeply explored works of Indian dance, which will have an enormous impact on future dance. My own company is now engaged in acquiring a few selected works of Chandralekha, for which much prior training in body conditioning exercises derived from kallari payattu (Indian martial art), yoga and other physical cultures i being imparted to my company dancers, who are training in one of her works at present. This process will continue for quite some time so that the company will be able to acquire a few other works too, which I find valuable for my company dancers. This is the kind of work for which I have recently set-up two important units in my company: MTDC Dance Lab and MTDC Unit of Contemporary Choreography.

Sudha: In a personal way, I had a strong link with Chandralekha both as a friend and as someone who fully believed in her and helped to promote her in Canada. Being a bharatanatyam dancer myself, I had seen her dance in the late 1950s when she was at the peak of her performing career as a bharatanatyam dancer. I continued to watch her until she suddenly dropped out of the dance scene altogether in the early 1960s because of her disenchantment and disillusionment with some aspects of the practice of this dance form. She then became a free spirit and explored her creativity in an amazing variety of things such as poetry, articles, haikus, a long prose-poem, called “Kamala”, hand-made books on ecology. She then travelled, doing nothing in particular, met with Merce Cunningham and John Cage in New York, and became subject of a poster and an experimental film. I briefly picked up the link when, in 1972, she produced a single landmark work, “Navagraha”. However, her real comeback to dance was in 1984 when she presented some very radical and insightful ideas on developing contemporary Indian dance at a seminar called East West Encounter. After that, she never looked back and her creativity became prolific and increasingly original. In 1993, I invited her to participate in the first Kalanidhi festival. We became much closer and spent many an hour discussing a variety of things about her views and experiences with contemporary dance. Those were the most pleasurable times of my life. She was a most warm and open person.

*An excerpted version of this interview appears in the December 2008/January 2009 print issue of The Dance Current.

Learn more:www.menakathakkardance.org

www.kalanidhifinearts.org

Tagged: Bharatanatyam, Choreography, Discourse, Festival, Indian, South Asian, Undercurrents | Courant Continu, ON , Toronto