When the news broke in Toronto that Rihanna and Drake were potentially shooting the Work music video in the city, dancers were eagerly waiting to hear the details. Then the closed casting call was released, and I saw something I wasn’t expecting: a $200 fee for the dancers who got the job. Many of us were fuming and I actually decided not to go to the audition. I was adamant to make a statement and take a stand because I was over Canadian artists being taken advantage of. But when the closed audition turned into an open call, I witnessed another major problem.

Half the city was auditioning for the dancehall video. Dancers, non-dancers, parents, children – everyone wanted a shot. I was teaching on the night of the audition, and I remember going on Facebook before my class and seeing my students posting about the audition. These were students who hadn’t taken a lot of dancehall classes or didn’t know the culture, so I got upset. This was a big chance for Toronto to be seen on the world stage again, and I wanted to make sure that authentic dancehall party vibes were present. So, I put on makeup, bought an outfit and went straight to the audition knowing I would dance my way into the video – and I did. I’m the one in the army tights and shining silver top; I’m even in a great slow-mo shot at the end.

I did this because I think representing someone’s culture should be done with respect. I spent years at dancehall parties, and I understood the vibe that the video needed. Many people see the music video and think that it is oversexualized, but they don’t know that it’s a representation of a culture and a people that need to be respected.

This is a fine line often danced around in our industry. It’s an elephant in the room that goes unnoticed because it makes people feel personally, socially, politically or artistically awkward. I will name it for you: cultural appropriation. As a choreographer/dancer in the dance industry in Canada, I’ve seen this elephant appear on stages, in music and on YouTube, Instagram and TikTok videos worldwide. I often cringe and stop watching because I wonder if the performers added certain moves for clout or for crowd approval. Don’t get me wrong, in some cases the choreography is hype. But does hype cloud appropriation?

Many people reside in a space where they feel persuaded by “inspiration” that often goes unquestioned, an inspiration that toes the line between appropriation and appreciation. So, I ask: how do we manoeuvre this inspiration to ensure we aren’t disrespecting people on our way to fame? I think there should be checkpoints to assess the differences between appropriation or appreciation: intent, purpose and give-back. A rubric or guide for how we assess ourselves and each other. It could allow everyone from teachers, students, educators, directors, agents, managers, jurors, grant officers, presenters, critics and more to be held accountable. Carrying the torch of policing appropriation shouldn’t fall on just a few sets of shoulders.

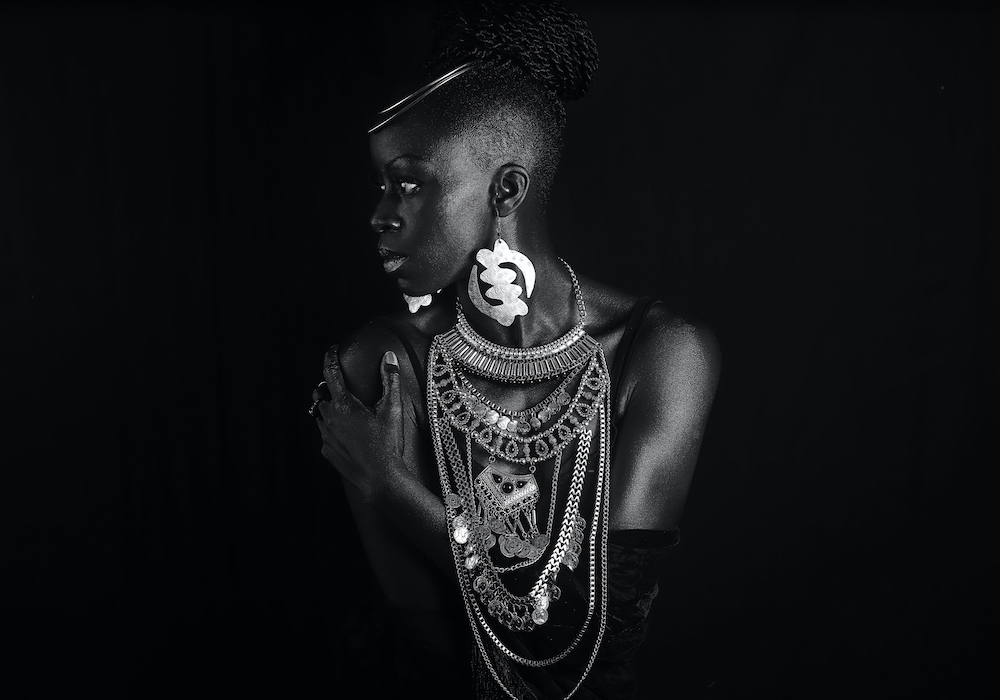

As someone who has spent thirteen years (and counting) in the dance industry, I know that unpacking this topic is essential. It’s tiresome, tedious, consuming and frustrating. Trust me, I get it. As a Black artist advocating for the voices of the marginalized, I find the weight of “educating the masses on what’s appropriate and not disrespectful” taxing. The development of my art and my voice fuels my role as an artivist – art activist. As a featured speaker at last year’s TEDxToronto talk speaking on shadiesm/colourism, I know that speaking about heavy topics isn’t always easy and is often triggering for listening ears.

When I was creating my original production Shades, I spent years deep in the topic of shadeism. The content was complex and I had to figure out how to navigate it. A singular viewpoint could not be applied, and keeping an open mind changed my point of view drastically. I decided to apply the same principles when examining cultural appropriation because it too is a Pandora’s box of feelings, entitlements and, most of all, information that can’t be ignored. I want to probe, hoping it results in more questions and education for all. A space where we can analyze what is or isn’t happening and create space for improvements. The culmination of the vast experiences in my career has given me a broader understanding and wisdom, which reminds me to stay balanced on loaded topics.

Here’s where I think you should start: what is your intention? I define this as your “why.” Why are you approaching this? Why are you inspired by this style? People’s intentions aren’t often in the right place, clouding their “why.” You may be inspired by a style from a cultural background that is not your own, so I invite you to ask yourself: why am I inspired? Is there an internal voice (spiritual call), an internal pull (indescribable feeling) or external intrigue (popular in mainstream media) that pulls you to this culture? Is this inspiration going to stay on the surface, or will it drive you to dig deeper?

It takes work to deepen your intrigue to something more internal and concrete. This brings me to the idea of purpose: What do you plan to do with this information? How do you intend to share this information? Do you see yourself as a caretaker of this information? Are you recognizing that this inspiration is rooted in a people that you may not know anything about and that your actions might be disrespectful?

This leads into my last checkpoint, which is rooted in respect: your give-back. How do you plan to give back to a community or people that gifted you with this inspiration? Are you invested in ensuring the legacy of knowledge gets passed down? How are you using your privilege? Brittany Packnett, A United States-based activist, encourages people to “spend” their privilege. “Race is not the only privilege one can have, but it is the most powerful,” she says in an interview with The Cut. She then asks: “How can you help remedy that situation? Begin to spend your privilege. You didn’t earn it, so give it away.” Even though this wasn’t said in the context of cultural appropriation, I feel the message still applies; understand your privilege and ensure you are doing your best to use it as a platform for those that need it most. As Packnett says, “Spending one’s privilege can carry consequences, but nothing important comes without risk and it’s worth taking one in the name of justice.”

About four years ago, a meme featuring my group Black Stars Collective dancing at a party went viral. Black Stars Collective is one of my companies, which focuses on an elite form of Afrobeats and Afrofusion dance – a contemporary African dance style. Ever since, memes of a white man dancing with a group of Black people have been floating around. Taglines read: “the key to end racism,” “Agent Ross after visiting Wakanda,” “Nick Nurse after the 2019 NBA Championship,” “Prince Harry after the Royal wedding.” The list goes on and on. That white guy is my good friend, and dancer in Black Stars Collective, Nasary “Nas” Volkoveski. He is a Ukrainian-born dancer that has spent the last ten years focusing on dancehall and Afrobeats. But that moment captured at a party sparked an online debate; people both love and hate this meme. The lovers say it’s great to see a white person embracing Black/African culture. The haters claim he is appropriating that same culture.

When the Internet made Volkoveski the centre of attention in a video that originally featured me, various emotions began to rise. I quickly felt invisible in the shadow of the only white dancer in my group. I had to be honest with myself and recognize that feeling invisible beside a white person is triggering, especially when it comes to your own culture. As a Ghanaian woman, my ego was bruised and I asked, “Are people only looking at race or is talent still a factor?”

Forty-five-second videos don’t show someone’s history or intentions. I know Volkoveski, so I can speak to his respect for the culture. I asked him to share his thoughts and he said, “Art, dance and music are meant to be shared, but in order for you to have a voice for people to listen to, make sure it is a voice that has depth and meaning backed with the years of experience you have laid out for yourself that others can respect. Let your work speak for itself and above all else put culture first as that is what gives meaning to everything that we love.”

People often feel they have a free pass to take without repercussion. An a la carte experience to pick and choose what they feel is hype from another culture, and discard the rest. We see this a lot in the fashion and music industries, but it happens in dance too. Why do people feel they can take without asking? Teach without knowledge? Profit without consequence? It’s because the opposition—typically represented by people of colour, and namely Black people—isn’t in a position of power to stop them from advancing.

Power dynamics play a big role. Dominant society is constantly taking from ‘marginalized’ cultures by packaging and reselling their work, and disregarding the lived experiences of these people. Society has made it known that it’s easier to sell stereotypes of Black culture when performed by non-Black people. If you don’t believe me, look at Miley Cyrus (VMA 2013), Katy Perry (Dark Horse), Taylor Swift (Shake It Off), Justin Bieber (Sorry), Iggy Azalea (Australian, not American), Jennifer Lopez and the Kardashians. If you’re still not convinced, look up Hound Dog by Big Mama Thornton.

Our society has been conditioned to believe that non-Black bodies doing Black forms can go further. Many times, my complexion has stood in the way of getting work both locally and internationally. Even something as simple as a club gig – a typical job for a commercial dancer – isn’t easy for a Black woman of a darker complexion to get. I am amongst other women who are often told that their look doesn’t work for certain clientele, even though the club plays “Black” music.

Some of you may be reading this and saying to yourself, well what’s the big deal if I’m inspired by someone else’s culture? Why would people be upset with that? Isn’t that a compliment? Put yourself in their shoes. With the explosion of the Afrobeats movement worldwide, the world is experiencing Africa in a brand new way. No more images of starving children covered in flies; Africa is actually popular, which is both exciting and scary – exciting because celebrities across the globe are doing moves like gwara gwara, shaku shaku and kupe, showing how accessible these movements have become. But did you know that Afrobeats evolved from the 2011 song Azonto by Fuse ODG, which was inspired by a traditional Ghanaian dance called kpanlogo (pronounced pan-lo-go)? The scary part is that everyone is learning these moves from the Internet. So, who can regulate or step in when you have an uneducated teacher teaching the style?

What makes me more qualified than other teachers on your timelines? Everyone is inspired by the movement, but few of us are the creators of the steps, so how do you determine who is qualified? As a teacher, I have to ask myself that question. I recognize I have to provide something greater than dance steps when people enter my class. I have to educate my students on different aspects of the Ghanaian/African culture to create depth in my practice and inspire them to do the same. I still feel I have a duty to my culture – I am not the only caretaker. I stand on the shoulders of many from across the continent and have a responsibility to teach my students the best way I can.

Ultimately, I went to the Work video audition to properly represent a culture. Intent, purpose and give-back still apply to me, and I do my best to take that role seriously. We should all remember to be students and learn how to be present for each other. Taking these steps will begin to heal a lot of old wounds.

~

This article was originally published in the May/June 2020 issue.

Tagged: Dancehall, Provocations, All