<i>In partnership with The National Ballet of Canada, through the Emerging Dance Critics Programme, we are providing one-on-one editorial mentorship and publishing exposure to a selected group of emerging dance writers who have demonstrated an investment in the field. Over the course of June 2014, this group of writers will produce reviews about the summer season, which will be edited according to our standards and posted in this dedicated column.</i>

If you’ve ever wondered what ballet would look like if Patsy and Eddie from Absolutely Fabulous had gotten their hands on it, you’d have an idea of The National Ballet of Canada’s production of Cinderella.

Choreographed by James Kudelka, (whose fantastic new work, Malcolm, premiered earlier this year featuring a puppet of the same name and the choreographer), the highlight was easily the two slapstick stepsisters performed by Tanya Howard and Rebekah Rimsay. Since he first reworked The Nutcracker for the National Ballet in 1995, former artistic director Kudelka has shown he has a golden touch, creating such works as Swan Lake (1999), The Miraculous Mandarin (1993) and An Italian Straw Hat (2005).

Yes, there was a Cinderella and a Prince Charming — on opening night Sonia Rodriquez and Guillaume Côté fittingly reprised the lead roles they danced a decade earlier. There was also a Fairy Godmother (Lorna Geddes) and a stepmother (Alejandra Perez-Gomez), too. And while all performers danced quite capably and expressively, the night belonged to Howard and Rimsay. From the moment they crept in en pointe, arms flailing wildly as they mercilessly taunted poor Cinderella, until the very end when they had to be restrained by their escorts, the stepsisters injected one of the most classical of ballets with humour and modernity. And that’s not even mentioning their immense dancing skill, as they deliberately parodied difficult techniques.

Ballet doesn’t always have to be tightly focused on form and function, and Kudelka is a master at recognizing this, as he was with Spring Awakening (1994) and The Firebird (2000). He intuitively understands how to work with a timeless piece of art to make it new again. Taking Sergei Prokofiev’s music (played by the orchestra with vigour and precision), set and costume designer David Boechler’s art deco theme and the National Ballet’s best dancers, he created a production that’s touching, enchanting and beautiful to watch.

Cinderella opens with a set that can only be described as magnificent: it’s a kitchen, but the cupboards and shelves are twice the dimensions they normally are, making it seem as though Cinderella’s chores are that much more insurmountable, and the fireplace is Harry Potter-like in its ability to let loose a stream of visitors from a lake of fog.

While the first half of Act I seemed innocent yet sad, (focusing on the humility and solitude of Cinderella), the second half was decidedly darker in nature, switching the set to a giant vegetable garden of Swiss chard and green onions. The vegetables were pale in colour, containing jagged edges that loomed over the characters, much like what would be found in a Tim Burton movie. But when pumpkin-headed men in tuxedos appeared, they capped off the first act in a whimsical, charming way.

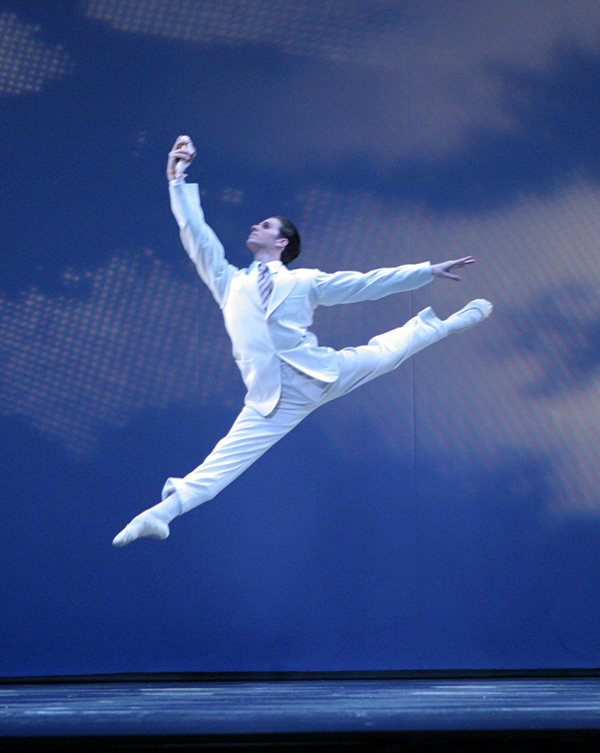

Act II is the ball itself, where we find Prince Charming forlorn and bored by the lack of female prospects in front of him. It’s a testament to Côté that he’s able to immerse himself totally in his character, whether he’s striding around in disgust or leaping in the air as lightly as a firefly. There’s a charisma that oozes from him, but Côté manages to give the impression that he’s completely unaware of it. When he meets Rodriguez’s Cinderella, the loveliest sparks fly between them during their pas de deux. Cinderella has just arrived at the art deco-styled ballroom by gliding down seated in a fantastical giant pumpkin. She alights with a grace that foreshadows her delicate steps, and the magic only increases from there. Rodriguez is able to dance as though she’s floating, her classical ballet steps constrasting with the jazzy moves of the corps de ballet. It is a delightful combination of ballet, 1920s dancing and modern innovation, and it carries on splendidly, even when the pumpkin-headed men arrive to signal Cinderella’s curfew.

Côté’s jetés were masculine and strong, yet he was sensitive and smooth with his lifts, and Rodriguez was as graceful as an angel when she pirouetted dizzyingly. There were a couple of moments where the lifts weren’t quite seamless, but they were barely noticeable and both dancers otherwise displayed clear, elegant lines and masterful grace.

It’s a sweet love story they live, one where both parties long to cast off the cloaks of convention and find something true and pleasing. Cinderella and the Prince start off on unequal footings — she the embattled housemaid and he the blue-blooded royal. But as is true in today’s society, romantic pairings from across the spectrum are possible and it’s one reason why this production of Cinderella speaks so successfully to contemporary audiences. What’s important is character growth, of being able to move forward with another person and meeting them in the middle.

If the first act was a study in contrast and the second was the crux of the story, then the third was the most visually daring and jaw dropping to watch. Prince Charming and his coterie of four dashing, strapping officers search the world high and low for Cinderella, approaching a bashful Japanese woman, an Amelia Earhart lookalike, a sizzling señorita, and a Scandinavian ice skater to see if the glass slipper fits. By the time Prince Charming does match the slipper with Cinderella, we’re firmly won over. This love story, danced with so much passion and energy, speaks louder than anything mere words could ever say.

But lest the audience think Kudelka has veered too far into maudlin territory, he ends the production with the stepsisters going for one last clutching, stumbling laugh.

<i>Reading Writing Dancing is one of The Dance Current’s educational programs, providing workshops, seminars, mentorship and professional development to emerging and established dance writers alike. As part of our commitment to the field, we partner with like-minded organizations to educate dance readers and dance writers, providing public access to dance art and culture, and facilitating dance literacy and appreciation.</i>

Tagged: Ballet, Emerging Arts Critics Programme, ON , Toronto