Our identity is partly shaped by recognition or its absence, often by the misrecognition of others, and so a person or group of people can suffer real damage, real distortion, if the people or society around them mirror back to them a confining or demeaning or contemptible picture of themselves. Non-recognition or misrecognition can inflict harm, can be a form of oppression, imprisoning someone in a false, distorted and reduced mode of being. ~ Charles Taylor, The Politics of Recognition

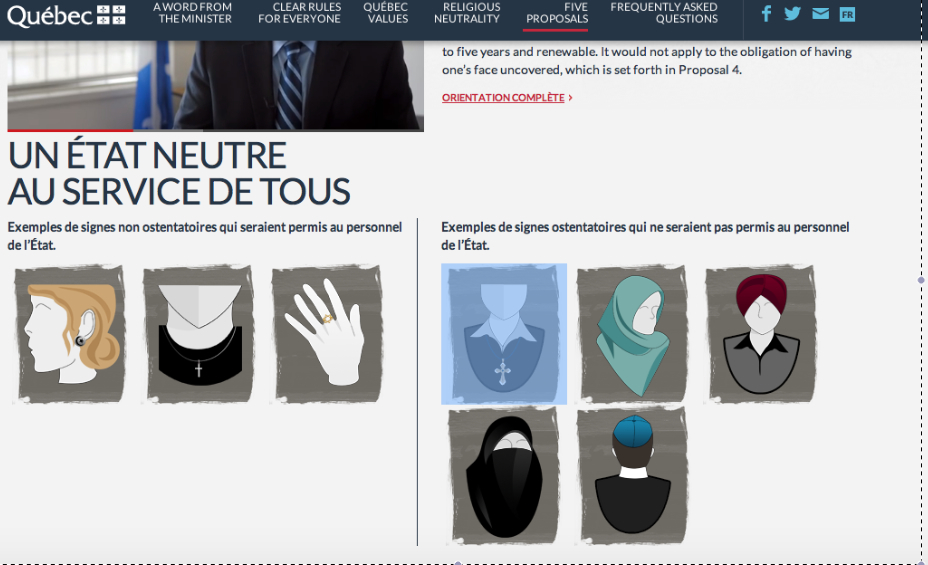

Over the last few weeks, Québec has been rocked by the introduction of the Parti Québécois’s (PQ) proposed Charter of Québec Values, in a divisive and heated re-evaluation of the social fabric. The minority government, arguing for a continued secular state, has been touting the importance of neutrality, achieved through the banning of religious symbols and headgear in public institutions under provincial jurisdiction – that would include courthouses, provincial offices, schools, hospitals, essentially anywhere that public employees might come in contact with the masses. In an official document made public on September 10, rules would permit employees to wear visible religious symbols – crosses, skullcaps, hijabs, turbans and the like – but only if they are discreet, i.e., small in size and not conspicuous.

For some, the cultural journey across territories encompasses the contradictions of the West and the East, or the North and the South. Shobana Jeyasingh, a British choreographer of Indian heritage, describes this intriguing shifting identity and representation in an essay entitled Imaginary Homelands, in which she references a dance she’d created called Raid and the inspiration she drew from a game called kabbadi, played on the streets of India, Birmingham, England and Glasgow, Scotland: “Even though it was a game of territories the border line was there for crossing. It was crossed and re-crossed the whole time and all the interesting things happened when the raider actually crossed and went over to the other side. While they were in their home ground nothing much dynamic happened at all.”

Many of my students at Concordia University in Montréal are raised by immigrant parents in one of Montréal’s ethnically diverse neighbourhoods. Considering cross-cultural identities in the arts is part of the syllabus in my course. Responding to Jeyasingh’s essay, one Filipino-Canadian student wrote, “I was born and raised by multiculturalism … to believe that being different from everyone was good. As I got older, I began to see how multiculturalism didn’t raise me properly; being different wasn’t accepted and it certainly didn’t make me popular. When I was finally able to identify the effects of my multicultural upbringing, it was too late. I had already settled into this ‘double-life’ of mine, living in many cultures simultaneously.”

That perspective of going to that “other side” that Jeyasingh mentions in her paper, reflects the thoughts of many who live through more than one culture. The territories to be traversed daily encompass living traditions at home, confronting societal expectations at school, and discovering the unfamiliar among friends. Incremental changes in an ever-changing process occur over time, and the “cross-cultural” becomes the defining aspect of their multicultural present. Differences exist between cultures but also there are differences within one’s own (superficially presumably uniform) culture. Paramount in my class discussions is the idea that the amalgam of cultures that students are introduced to not only bring out a different side of them, but also immerse them in the unknown.

The immigrant reality varies, but it embodies the legacy of generations of people forced to travel to escape tyranny or oppression, in order to pursue a better life in better economic conditions, or to provide daughters and sons equal education. These are the living, breathing realities of diversified cultures. And while policies of multiculturalism are heralded in the rest of Canada, the Québec government fiercely rejects this federal concept.

There have been grandiloquent speeches from various PQ cabinet ministers in the last days and weeks, speaking on behalf of “neutrality,” a concept of monoculturalism that is equated with “normalcy.” But if everything is “normal,” why are so many people upset? Criticism and opposition expressed in the rest of Canada, as well as from individuals and groups inside Québec, has been met with derision and defensiveness by the government. Public opinion polls, meanwhile, show a significant percentage of Québecers from outside of Montréal heartily supports the idea.

The government is telling citizens that it is fighting for the equality of women in Québec. But it is also telling women to give up their religious symbols, which many women and men will not under any circumstances do, and that includes covering their head. There is general consensus that a secular state is needed in Québec, and the presence of a woman wearing a niqab or burqa – in which her full face or body is covered – in the provincial workforce is problematic: i.e., seeing a person’s face is not only helpful but viewed as a necessity in these public positions. But the message back from many citizens is that they will not have politicians “impose” their beliefs on them, encroaching on personal choice, and religious and social freedoms. It’s true that misogyny and brutal codes of shame and honour exist throughout the world, but how is a charter of values, designed for the Québec public workplace, going to change those realities? Further, these discriminatory propositions might force members of cultural communities to leave their jobs, or exclude them from entering certain professions in the first place.

What’s being proposed by the Charter of Values is that in a “neutral” Québec a citizen need not have to negotiate their space/place/environment in relation to “otherness.” Premier Pauline Marois has suggested that a woman supervising a daycare would be indoctrinating her young charges if wearing a religious symbol. The government now says that some school boards could opt out of the regulations, for a period of five years, giving them time to “transition.” The federal government has weighed in, stating that the Charter would likely be struck down in a challenge put forward to the Supreme Court of Canada. Meanwhile, the crucifix placed in the National Assembly in the late 1930s at the height of the bad old days of the reactionary Duplessis government would remain on the wall because of its “historical and heritage distinction” say the politicians. The PQ insists it is a symbol of, not religion, but identity and its firm stand on the crucifix issue signals and reconfirms the symbolic dominance of the white, French-speaking Catholic majority in Québec. Some pundits, in view of this stance, are branding the Charter proposals ethnic nationalism.

The evolution of modern-day Québec contains a complicated narrative. Language, of course, has been raging as a front-burner issue for decades here, but to equate this current charter with the adoption of Bill 101 – which enshrined the primacy of French in the province – is specious. But it’s analyzing the stranglehold the Roman Catholic Church had on the greater population until the 1950s that prompts greater understanding. In the early 1900s, when industrialization and modernization were fundamentally shifting the landscape of Québec, clerical nationalism and cultural isolationism were shunning foreign influences and immigration. In her book Dancing in Montreal Iro Tembeck notes, “In 1927, the bishops expressed… fears in a statement that underscored the strategic rejection of the present.” She cites Jean Laflamme and Rémi Tourangeau’s book, L’Église et le théâtre au Québec, revealing the ideological turmoil of the period through the words of the clergy: “A wind of sensualism blows from foreign lands over our beloved country. Ways of thinking and living, incompatible with Catholic principles, are corrupting Christian consciences and spreading with alarming speed.” Today’s churches, by contrast, are near empty. In fact, many Québécois have spent a lifetime throwing off the shackles of the Church and, perhaps because of that, can’t see or are confused by the implications of the Charter.

Born and raised in Montréal, I attended the English Protestant school system in the city in the early 1960s, because Jews were forbidden from entering Catholic schools. At the time, we were governed and regimented by the predilections of the board’s “norms” – our daily drill started by saluting the flag, singing God Save the Queen, bowing our heads for a rendition of the Lord’s Prayer, and then opening our red or green prayer books to sing a daily allotment of Christian hymns. I never saw it as repressive. The Lord’s Prayer was, for me, a word game – I’d chuckle to “Our Father who art in heaven, Harold be thy Name.” Those days are long gone. When I celebrate my partner’s Advent church service festivities, I find it ironic that the Jew in the room seems to sing Onward Christian Soldiers with equal or more gusto than most of the other parishioners. Let’s be clear: I have not been converted to Christianity, and it certainly would not have happened because I sang hymns in school. The spirituality of the words doesn’t have import for me. I just like the tune and the cultural encounter.

Did I, as a child, experience “indoctrination,” which Madame Marois insists will occur if a hijab-wearing woman instructs a kindergarten class? No, and from my perspective it honestly didn’t seem like confinement either. It was a matter of being in another reality, which has served me well later in life.

About a decade ago, and for three successive years, I was invited to speak at a friend’s Religion and Ethics class in an east end French CEGEP. My task was to share ideas about Judaism and what it meant to be a Jew in contemporary times, especially in the demographically varied environment of the city. One of the first questions I’d ask the sixty or so assembled students each time was, “How many of you know someone who is Jewish?” or “How many of you have met a Jew?” The first year one person raised their hand, stating they had passed through the neighbourhood with a great concentration of Hasidim. No one else had made a single contact, at least to his or her knowledge, with a Jew. Each year it was the same story. Twenty years before, I was in graduate school in Montréal and two of my classmates, who’d grown up in the suburbs across the river, found out one day that I was Jewish. They weren’t shocked and were quite happy to be friends, but I too was the first Jew they’d encountered. To be frank, this kind of rapprochement is what is needed, not laws dictating unsatisfactory terms and conditions of “acceptable” cultural norms and dress codes, or the marginalization of culturally diverse peoples.

In her essay The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House, writer and activist Audre Lorde argues that the mere tolerance of difference is not enough if we want to effect change in the future: “Difference must be … seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic. Only then does the necessity for interdependency become unthreatening. Only within that interdependency of different strengths, acknowledged and equal, can the power to seek new ways of being in the world generate, as well as the courage and sustenance to act where there are no charters.”

The Québec Charter of Values conveys a narrow righteousness. The gathering anxiety it has provoked, including growing public expressions of intolerance, suggests that life in this province is, to quote Shakespeare, deeply “out of joint.” It appears that complexity is not Marois’s strength, nor the PQ’s, and its approach to societal peace and resolution does not inspire confidence or calm. Due to this legislation, she may indeed win key votes in the regions of the province outside of Montréal, where the PQ’s base is greatest, whenever the next election is held. But the kind of careless certainty that the government is coasting on, reinforcing a different form of patriarchy, suggests that Marois, her party, and her followers, will always be lost in this land, even while in power, mired in the past, walking in the shadows of strangers.