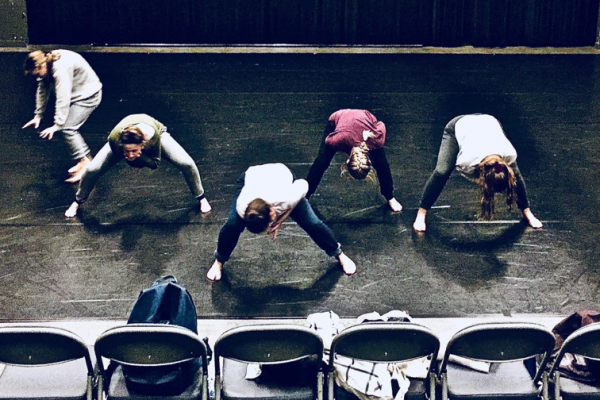

The opening night of Ascension on December 6th felt like a remarkably intimate affair. Held in a black box studio in Simon Fraser University’s Goldcorp Centre For the Arts, the venue reflected the minimalist sincerity of the program. Simple in layout, the moderately sized studio blurs the line between spectator and spectacle, with a single row of folded chairs demarcating the separation of the stage and audience.

The show proceeded much like a friendly gathering. In a short and heartfelt opening speech, Artistic Director Charlotte Telfer-Wan seemingly addressed us as a class of familiars; bouquets in hand, fellow collaborators and well-wishers congregated in the studio and hallways pre-show. I found myself here on Thursday evening, reveling in this intimacy.

Going into its seventh year, Ascension is an annual collaborative production by undergraduate students of SFU’s School of Contemporary Arts. Interdisciplinary in nature, it brings students from dance, music, theatre production and design, and film programs into conversation; the fact that students take complete creative control makes the maturity of the production all the more significant.

This year, the endeavor takes shape in five dance pieces and two short films. In the absence of a single narrative thread, the shared creative sensibility of the collaborators nonetheless felt palpable: passion, skill and vision intertwined into an inextricable skein.

The program begins with A Contemplation of Nothing Too Serious (choreographer Kestrel Paton, composer Ben Berardini, lighting designer Mashid Maleki), as four dancers take the stage in a rhythmic sequence. Lively music accentuates the animated fluidity of the dancers’ movements, and a shifting, multicolored lighting design amplifies the piece’s ethereal elements. The sensuousness of the piece immediately drew me in: so close to the stage, I heard every jump, step and sigh punctuating the fabric of the work.

Possibly an ode to Dante’s Inferno, Void (choreographers Jaqueline Ritter and Cleo Agar, composers Angela So and Stefan Nazarevich, lighting designers Mashid Maleki and Samaya Aldaker) further highlights this multisensory experience. Against a projected backdrop of twisting, barren trees, dancers perform an intricate chase amid the infernal forest. Here, the body conducts not only movement, but also sound: crucially, a sound both intimately heard and felt. The breathing of the performers and the booming crescendo of the music heighten the choreographed hunt, which ends rapturously.

Moreover, 5 Years (choreographer Seana Williams, composer Sam Meadahl, lighting designer Margery Liu) skillfully embodies the marriage of sound and movement. The piece begins without musical accompaniment, but do not mistake this for silence. As dancers move wordlessly, they expel sharp, dagger-like breaths; the body speaks for itself. Alongside an elegantly sparse composition, every sudden respiration and exquisite rustling of clothing finds its way into the soundscape, honed to a piercing acuity. Watching this transpire within a political landscape where speech is increasingly weaponized felt like bearing witness to something powerful.

Two films explore the intertwining themes of movement and intimacy. Body (2015) (film by Emily Bayrock) captures the macro-graphic; alternating between vignettes and title cards, it presents close-ups of various body parts intercut with words like “LOVE” and “BODY” in rapid succession. Unfolding (film by Brenda Nicole Kent) highlights experiences of solitude and connection; throughout interrelated shots, performers attach and detach themselves from each other, physically embodying trust, bonding and interpersonal ties.

Lumiere (choreographer Brett Palaschuk, composers Daniel Blackie and Eli Saltzberg, lighting designer Margery Liu) exudes an almost geometric quality. The performance begins with synchronicity before dancers break away; they move in tandem until they do not, their forms supple and flowing until sharpness contorts every extension. But the piece does not delve into disorder: these spiraling vessels achieve a greater unity as dancers move in individualized unison.

Similarly, Snare (choreographer Anja Graham, composer Benomi Maratovic-Brome, lighting designer Samaya Aldaker) creates a dialogue between order and chaos. In a memorable sequence, dancers repeatedly sprint across the stage in a directed frenzy, until one by one they fall into moving synchronously – perhaps a comment on the desire to resist but ultimately surrendering to structure. By way of either curation or coincidence, these final pieces voice a continuing discussion on movement and unity.

In an interview, Telfer-Wan stated that it would be a political statement to say Ascension is “just dance”. Taking this to mean that labelling is a political act, I depart with further questions: Specifically, what can we take away from these deliberations on bodies, chases, speech, unity and structure? Overall, how might we read Ascension in a political landscape where “movement” carries a multitude of meanings? What is the relationship between art and its interpretation? Not only an interdisciplinary dialogue between collaborators, Ascension seems to pull the audience into its folds.

No element of Ascension felt gratuitous: the unembellished studio, stage and costumes all point toward an intimate simplicity. Yet through this aesthetic of minimalism the program showcases the maximalist sincerity of its creators.

Ascension challenges the sacrosanctity of the lone creative genius, reminding us that the nature of art is collaborative. The result of shared artistic and intellectual labour, Ascension proves that a labour of love provides room for meaningful discussion.

Ascension ran December 6 through 8, 2018, at 8pm at SFU’s Goldcorp Centre for the Arts.