Having been a kid who danced in the early 1980s, the benchmark for all narrative dance films was set by Dirty Dancing. Jennifer Grey, Patrick Swayze and Cynthia Rhodes shone a light onto forms of dance that I had never imagined. Years later when I found myself sitting one table over from Jerry Orbach at Compass Restaurant on the Upper West Side, it was Dirty Dancing that came to mind, not any of his other (perhaps more impressive) performances. Because not only was I in the same room as Dr. Houseman, I also happened to be sitting in the corner. It was immensely satisfying.

Test, released in 2013, is a film set in San Francisco in 1985 and, like Dirty Dancing, benefits from a cast of extraordinarily skilled actor-dancers. It is a coming-of-age story of an apprentice dancer and a young gay man. In that precarious time in which the AIDS crisis threatened queer identity from within, while heteronormative society oppressed from without, the protagonist Frankie (played by the intrepid Scott Marlowe) — transitions from stand-in to leading man, bi-curious to self-assured gay man.

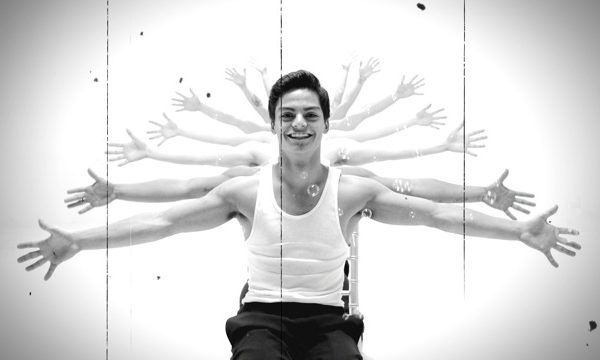

The choreography in this film is exceptionally compelling, especially given this particular brand of narrative film. Instead of using dance as a loose structure on which to hang a coming-of-age narrative, the film foregrounds the role of the arts in personal transformations. Choreographer Sidra Bell has done an incredible job, too, of mapping the protagonist’s story onto the performance piece within the film itself. And she does so in a nuanced and breathtaking way — this choreography would stand up on any stage. While the dancers move one forgets that this is a film with a story because, for a time, the dance actually is the story. Unlike so many other dance narratives, writer-director Chris Mason Johnson actually lets us get into the dance as though we were at a performance — providing many prolonged shots.

The film gives considerable airtime to the processes that lead up to performance. Some of the most extraordinary scenes happen during the rehearsals where the strangely banal warm-up rituals of the dancers prove that they’ve really got the chops. There is a strange pleasure, too, in watching the dancers as they limber up before rehearsal because these types of movement are rarely incorporated into choreography as such and are rarely given visual form. Instead they are often seen as the preamble to the real art, but they are nonetheless foundational and essential. Test reminds us that watching dancers walk, wake, or just move through the spaces of everyday life, is interesting and artful.

Accordingly another subtle and intimate moment occurs in the doldrums of rehearsal. Having just practised a particular bit of choreography, the choreographer stops the dancers and asks them to take it from the top. We then witness the same piece of choreography for a second time, and Mason Johnson should be commended for including this visual do-over because it feels like rehearsal and that is astounding in itself. This temporality is what queer theorist, José Estaban Muñoz explores in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. For Muñoz, “utopia is a stage, not merely a temporal stage, like a phase [in the future] but also a spatial one,” an actual stage. On this stage, which looks towards the future from the position of a difficult present, what counts is the process and the unfinished, “the moment before an actual performance, the moment of potentiality.”

Toward the end of the film, Frankie calls his friend Todd and says “Fuck art, let’s dance,” and the two head out for a night on the town. I recalled a particularly irreverent night in Montréal I had with my friend, poet Lucas de Lima, where we wanted to drop our seriousness and express something wild. The prolonged scene of these two characters dancing in this shabby, lo-fi space is beautiful, not least because of the extreme joy on their faces. This kind of dancing in this kind of space, the film reminds us, is important to queer history. The point is that dance accesses and negotiates boundaries between the personal and the public body, the present and the future, but it does so in real, lived spaces, as well as on the stage and in rehearsal. As medical discourse and technologies of health converged on gay subjects in the 1980s around HIV/AIDS, (threatening to name and make public what might otherwise have been felt as a highly personal matter), the bodies of the dancers in the film negotiate parallel codes of privacy and legibility rooted in the body. Unlike Dirty Dancing, which explored dance as a tool for transgressing, and ultimately reinstating, class divisions, in Test dance forges intimate communities necessitated by the precarious conditions of the time. It insists that queer dance, like love and life and passion itself, must continue, even if it is still a work-in-progress.

Test will be screening at the Vancouver Queer Film Festival, August 14-24, 2014. Learn more >> queerfilmfestival.ca

Tagged: Dancefilm, Film, Screening, International