Probably the most famous couple in dance history is Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire. While not as well-known as them, Robin Poitras and Ron Stewart — she of Regina, he of Vancouver — have a history of dancing together that dates back to 1998, when Montréal choreographer Bill Coleman teamed them in “Zurich 1916”. Since then, they’ve performed in such productions as Susan McKenzie’s “Proverb” (1999) and “Dark Isle” (2000) through Curtain Razors, a Regina experimental theatre company. With “Reve a Deux” (co-produced by New Dance Horizons and Mascall Dance) they commissioned Toronto’s Sarah Chase and Vancouver’s Jennifer Mascall to choreograph duets for them.

Having seen Chase perform “Portraits/Mapping” in Regina in January, I found many resonances with her duet “Drownproofing”. For “Portraits”, she visited ten Europeans, strangers all. After spending a day exploring their homes, she conducted interviews with them. Then, through a blend of storytelling and dance, she created portraits of her subjects. She followed a similar process with Poitras and Stewart, interviewing them about their family histories. Prior to doing so, she said, “I was drawn for some reason to the image of two people who’d weathered the elements over a long period of time. I was thinking [in particular] about what it would’ve been like to [live in pioneer days], and how incredibly strong people would’ve had to [be].”

Dressed in simple clothing evocative of pioneer times, at the outset Poitras and Stewart execute a series of promenade-type steps from the back to the front of the stage, then move backwards to their original starting point. Above them, a ghostly moon hovers, while around them swirls the haunting sound of the wind. Using a “she said/he said” format, Chase, in a pre-recorded voice-over, recounts memories gleaned from the dancers — among them, Poitras’ recollection of washing her hair as a child, braiding it, then having the braids snap off in her hand while crossing frozen Wascana Lake with her cello strapped to her back during winter; and Stewart, while preparing for a performance in eastern Canada, being overwhelmed by a sudden feeling of sadness, and learning the next day that there’d been a death in his family.

The dynamic evoked by Poitras and Stewart — both through gender and the fact that they moved largely in unison with each other — was that of a married couple. As with every relationship, they would have led separate lives prior to meeting, falling in love and deciding to build a future together. Despite the distance that separated the dancers while growing up, Chase revealed an interesting parallel between them in another anecdote — to wit, Poitras’ father, an architect, designed the community centre in the small British Columbia logging town where Stewart’s English grandparents settled after immigrating.

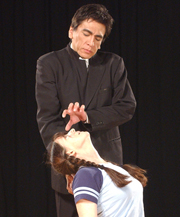

Once Chase’s narration ends, Poitras and Stewart move diagonally toward a spot on the floor, lit to resemble the moon’s reflection on water. They stand over the light for a time, as if in thrall of its beauty, and then move back across the stage to the strains of Rachmaninoff’s concerto “Vocalise”. They pick up long sticks, insert them into the back of their clothing (recalling Poitras’ cello anecdote), then place them horizontally across their shoulders, and finally lay them on the floor to create a doorway. Moving with grace and elegance, Poitras and Stewart evoke the notion of mutually supportive partners until the end when she slips from his arms and walks through the opening. Does she leave him of her own volition? Perhaps. But equally probable, if not more so, is the likelihood the couple is forced apart by circumstances beyond their control– specifically, her death.

Leading off the evening was Mascall’s “Fielding”. Upon receiving the commission, she said, “I realized that the work that interests me at the moment is a detailed investigation of small movements, and the huge effect they have.” Thus, she elected to focus on Poitras’ eyes and Stewart’s hands. “They’re not exploring their physicality, they’re exploring an impulse in them that makes a physicality,” she insisted. “But we know — the dancers and I — it’s completely about communication. If the audience is attentive enough, they’ll be able to feel the dancer’s whole being.”

Recognizing that the subtlety of movement might be difficult for the audience to discern, Mascall collaborated with videographer D-Anne Trepanier to project imagery on a huge screen. Prior to Poitras and Stewart taking the stage, there is video of two children playing on a fog-shrouded beach. After briefly facing each other on opposite sides of the stage Poitras squats down in front of the screen and looks out at the audience. Behind her is a close-up image of her face superimposed on a grassy field. Initially, I thought the image was a real-time projection. But it soon became apparent this wasn’t the case. While such an arrangement would have helped the audience better appreciate the nuances of Poitras’ facial ballet, the disjunction between her and her video doppleganger did give the latter a timeless, iconic quality consistent with the land itself.

After approximately ten minutes, Stewart joins Poitras on stage. Christopher Butterfield’s atonal soundscape, with its strong evocation of urban/industrial life that I occasionally found grating (especially the Harpo Marx-like horn honks) suddenly becomes even more frenetic. The dancers writhe violently on the floor for a short time before Poitras withdraws. With a close-up image of his hands projected behind him, Stewart stands in front of the screen and executes a series of hand gestures that also encompass his arms and torso. The more expressive nature of Stewart’s movements results in a stimulating dialogue between him and his video referent. Particularly effective is a segment where the hands are depicted repeatedly grasping at air, which makes it seem like they are trying to scoop Stewart up. Once his solo is done, Poitras joins him and they again engage in a frantic dance — this time while rushing madly about the stage — that was intended to explore the “constructed space” between them. While an effective counterpoint to the more sombre movement in the solo works, I found the execution somewhat forced.

Had New Dance Horizons presented “Drownproofing” and “Fielding” separately, most viewers, I suspect, would have left the theatre unsatisfied — having found the former too sedate and predictable, the latter too outré and abrasive. But combined into one program, they articulated for viewers the breadth of contemporary dance practice.

Tagged: Contemporary, Performance, Regina , SK