VIVO Media Arts Centre is off the beaten track in Vancouver — near the eastern edge of East Van, where Broadway Street stretches past the congestion and opens out. Just south of that large road and a few streets above the train tracks is the venue entrance, an artist-run centre dedicated to media arts.

Across four evenings this June, VIVO presented Tender Engine, a performance-installation piece co-choreographed by Alexa Mardon and Erika Mitsuhashi. The artists have been in research for over a year through residencies in Vancouver and Halifax, during which they investigated four areas: technology, language, storytelling and “performative expertise.” The resulting seventy-five-minute show is a unique journey of three parts that move the audience around the gallery. From the start, it feels a bit like a tidal wave, pulling the audience into a generous space of questioning. At the end I’m reluctant to emerge from its depths.

Pre-show, an energetic and hip crowd mill about the bar and large gallery space. The space is framed on one side by black garage doors, dotted with white plinths displaying small plastic objects and sectioned off by white mobile walls. The four performers (wearing oversized white shirts, black shoes and loose trousers) are setting up. Mardon walks by, twirling a roll of silver duct tape. With a pencil tucked behind one ear, Mardon asks a few audience members if they need anything and assures them the show will start soon.

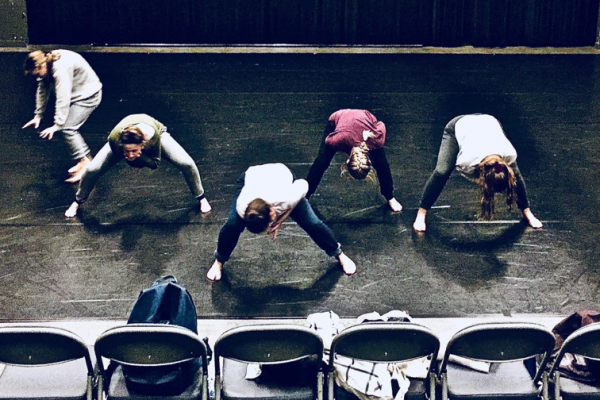

When the lights finally dim, the four dancers — Mardon, Mitsuhashi, Zahra Shahab and Elissa Hanson — casually make their way to the outer walls. Mardon thanks everyone for coming and explains that before the show starts, they plan to remove the pencil from behind their ear. After a short pause, they do.

In turn, each of the dancers announce an action, describing it quantitatively (including angles, percentages and directions) before completing it. Shahab states, “I will now perform a series of movements moving westwards, ending in an interesting yet comfortable position,” before flopping around on the ground to finish with both legs up. These announcements and action-dances begin to layer together and expand physically into short phrases. The dancers feed off each other’s words with repetition. On the wall, a projection blinks code of unknown importance, with occasional phrases that read “Change the Space,” “Text to Screen,” “Make, Unmake,” “Offstage Body.”

This amusing “soft start” sets up several codes of performance that persist for the rest of the night. First, the dancers are accessible and casual, befitting a gallery setting. Yet they slip in and out of a more formal physicality that shows off-fluid, off-balance improvisations filled with gestures and pauses. Second, the use of text is pervasive, sometimes overwhelming the senses. It is spoken by the performers, incorporated in the sound score and constantly projected onto the walls.

After an adjustment of the mobile walls, and some uncertain audience shuffling, the dancers move into a new section of the gallery where projected code and text (like a scrim) backdrops the entire space. And, for the first time, I witness a form of artificial intelligence that truly participates as a performer inside a work. The projections in Tender Engine are UXIE, a recursive neural network trained on a dataset composed of language. The system, developed by programmer Brynn Catherine McNab for the work, uses language gathered from listening to a year and a half of rehearsals to generate phrases and instructions.

In this middle section, UXIE instructs the performers with random generated text on the screen. First it reads: “ERIKA will output UNMAKE with OFFSTAGE BODY.” Mitsuhashi responds by moving around pieces of the set and unplugging cords, while stopping to adjust her clothing or tidy her hair. Next: “MARDON will output FORECASTING with TENDERNESS.” Mardon steps out and revisits the action-dances from the beginning, speaking with a soft, heartfelt tone.

Why is it so satisfying to watch the performers obey UXIE’s instructions? Perhaps because for the first time, I completely understand what’s going on. As UXIE generates more and more instructions, an electronic sound score builds, and the performers slowly break away from the task to respond with improvised movement. There is a strange, loose-ankled floppy quality to their dances, which is somehow controlled. Here and there, the dancers pause before melting and morphing into new shapes. Hands slice and curl around bouncing bodies as the text on the screen begins to repeat the word TENDERNESS in patterns like wallpaper. Eventually Hanson and Mardon adjust the walls, and the show bleeds into a third section.

In a final corner of the gallery, the dancers dive into personal stories describing objects of sentimental value. Large transparent screens hang from the ceiling, catching words from projections of UXIE and refracting them around the room. The performers take turns holding 3D-printed versions of treasured objects and describing their importance, as lights dim and a low drone hums like a helicopter in the background. Something about this section feels quiet and sombre, under low pink light. The performers cradle their objects, as screens and projected text visually cradle their own bodies. As it gets darker, the stories become deeper and more personal.

When Mardon gently announces the end of the show, no one claps. Instead, as if underwater, people quietly move back towards the entrance. I notice a collective feeling of being bonded through experience, which is perhaps connected to the way the work physically moves the audience through space. It makes Tender Engine feel like a journey: it requires time to come back to reality. Though at moments the show resembles more of an installation, it manages to attain the same intimacy of a theatre, finding a sweet contemplative spot between gallery and stage. Days later, the lasting sense of the work is the rich performative space created by the artists, punctuated by amusing, quirky moments and intriguing technology.

Tagged: Contemporary, Elissa Hanson, BC