The Prairie Dance Circuit (PDC) produced a bounty harvest of five premieres with its second annual touring production by the same name. The mixed repertoire show opened in Calgary before officially launching Winnipeg’s Contemporary Dancers’ (WCD) forty-seventh season. I caught the show at Winnipeg’s Rachel Browne Theatre on October 29th before it resumed a four-city western Canadian tour that also included stops in Edmonton and Regina throughout November.

The PDC is a collaborative network of five artistic directors: Brian Webb (Edmonton’s Brian Webb Dance Company); Robin Poitras (Regina’s New Dance Horizons); Calgary’s Davida Monk (Dancers’ Studio West); and Nicole Mion (Springboard Performance) as well as WCD’s Brent Lott who birthed the project two years ago. Last year’s program showcased emerging artists from each of the four home cities. This year, audiences were treated to a rare cornucopia of solos and duets choreographed by the well-established directors themselves — with fascinating results.

Monk’s riveting solo Under Cover of Darkness is simple in construct and razor sharp in meaning. Wearing simple black pants and top, the muscular Monk struggles to remove a “hoodie” sweatshirt — clothing as carapace — while drawn to another T-shirt positioned downstage. The defiant shedding of her metaphorical snakeskin only to don (and shed) another layer becomes a transformative journey about self-identity itself. Her spinning duet with the T-shirt held against her chest is underscored by Frangiz Ali-Zadeh’s prepared piano and cello score Habil-Sajahy, which erupts into pounding, tabla-like rhythms. As the solo ends, Monk’s ecstatic dancing in a pool of light reverberates with the joy of self-discovery and hard-won acceptance.

The most startling work of the program was Webb’s solo 30% gone, choreographed after the Canadian dance innovator suffered a heart attack last October. The piece begins with Webb telling a tale of his dying father, pacing the floor in an everyman’s business suit and tie as he recounts the graphic details. His fluid movement becomes more dynamic as he appears to symbolically travel through time. Webb then proceeds to take a walk on the wild side by stripping and strutting down a brightly lit runway like a model, garishly voguing in defiance of age. His pink baby doll negligee adds to the absurdity of it all, capped by breathy vocalizing of Lou Reeds’ Walk on the Wild Side into a microphone that sets up viewers for what is to come. When Edmonton composer Dave Wallace’s electronic score suddenly jolts – like nightmarish EKG blips — a flailing Webb onto the floor, the effect is harrowing. When he rises again, silently tracing a blood vein like a map to his heart, the work reveals itself to be a brutally honest tale of personal survival.

Another piece about the ravages of time – albeit through the lens of inter-generational relationships — is Lott’s The Occasion of our Passing. The mature duet performed by the forty-seven-year-old Lott with WCD company member Sarah Roche – twenty-one years his junior — resonates with an emotional poignancy borne of experience. This piece reminded me of WCD founder Rachel Browne’s Flowering (2005), also an intergenerational duet, which premiered at Toronto’s Older and Reckless series in March 2007 and was performed again at the inauguration of the Rachel Browne Theatre in May 2008. In Lott’s piece, set to Haushka and Hildur Guðnadóttir’s Pan Tone #283 and #294, the duo perform as equals, locking eyes as much as they do arms for physical support. When the older dancer fixes his gaze upon the younger, it’s as if he is watching himself onstage many years ago. Their fluid movement grows more vigorous with lifts and falls, kicks and rolls, as an intimate dialogue between two respectful partners that speaks to the continuity of generations.

Mion’s Quiver proved to be the most introspective offering of the program, interpreted by Vancouver-based dancer/improviser/choreographer James Gnam alternating with Calgary’s Jenn Jaspar who danced in the other centres. Gnam performs the abstract solo, with graceful fluidity that steadily grows in intensity. Mion’s created, naturalistic world is heightened by Kimmo Pohjone’s sounds of running water and low flutes. Gnam’s pulsing movement with his body seemingly in constant motion includes body isolations, twisting and tiptoeing as though precariously walking a tightrope. When his hooded sweatshirt obscures his face, his body becomes an objectified canvas devoid of personality, save his gaping mouth. I thought it would be fascinating to see this improvisatory-style work performed by another dancer who would undoubtedly bring his or her own aesthetic.

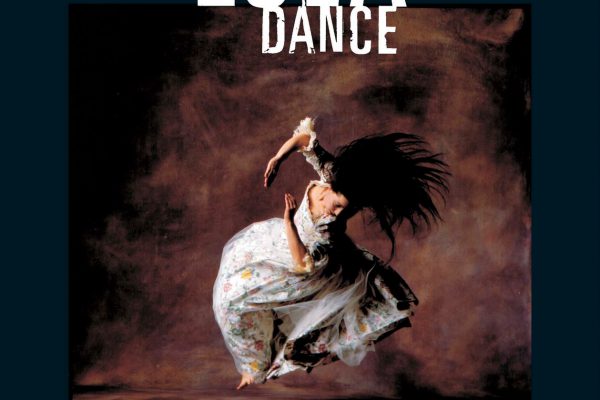

Last but not least is Poitras’ soft foot, choreographed as interplay of myth and body memory inspired by the constellation Ursa Major. Its title refers to a term coined by Saskatchewan-born dance artist, and Toronto Dance Theatre charter member Amelia Itcush, who died last May. Poitras creates mesmerizing eye candy as lithe, semi-nude dancer Ziyian Kwan navigates the stage with long rods and furry bear high heel shoes (created by John Noestheden) lit, as with the entire show, by Edmonton’s David Fraser. A large ball positioned upstage evokes various objects: earth, or moon; Kwan sits atop it while reciting Robert Bringhurst’s text. Jeff Morton’s rumbling, sub-sonic score creates a backdrop for Kwan’s tale of a warrior who discovered he was married to a bear. The solo flows as a series of body memory images as Kwan falls against the floor, howling with grief until ultimately melting into soft chanting. Some of this felt overly cryptic; however, Poitras’ ability to create sculptural dance still communicates despite a lack of clear narrative structure.

Dance makers and critics have long grappled with the question as to whether a collective Prairie aesthetic exists. This show provides further grist for the mill. Although no conclusions can ultimately be drawn, witnessing a cross section of work produced across the three Prairie provinces is an excellent start. Nonetheless, I would make one suggestion: the eclectic show ran at nearly two-and-a-half hours, thereby testing, or perhaps overestimating, the audience’s capacity to absorb all the images. In future, another challenge worthy of consideration might be to provide choreographers a prescribed time limit in which to express their individual voice – or else highlight only a few artists each year. This would result in a tighter, more cohesive show while still offering the finest of Prairie dance. Although the question of a collective aesthetic remains an intriguing puzzle – and one that hopefully will continue to be addressed as The Prairie Dance Circuit evolves — the timeless adage, “less is more”, still rings true. Of this much, I am certain.

Tagged: Contemporary, Performance, MB , Winnipeg