The first choreographic adaptation of Christian Bök’s pièce de résistance, his conceptual prose poem Eunoia (2001), as conceived by Denise Fujiwara is tremendously delightful, witty and entertaining, yet nevertheless … somehow … a letdown. Partly the problem is the very tall order that Eunoia presents. Over the course of seven years, in five chapters — respectively A, E, I, O and U — and seventy pages/paragraphs/stanzas, Bök composed a work of unlikely unity of purpose, narrative integrity and linguistic liberty, all the while imposing a most severe restriction, by limiting himself in each chapter to words that contain only the designated vowel. Bök reading Eunoia (or any of his sound poetry) is a marvel of verbal ferocity, as headlong and committed to words as phonics (and sonics) as to text. Fujiwara and her troupe take a different tack, opening the poem to a big-top multitude of possibilities, interpretations, analogies and associations. They embark on a preordained course of absurdity and jollity, expanding the notion of choreography well beyond dance and movement, and, from the start, rouse their audience into the spirit of the show. However, somewhere along the way, the essential threads fray and get lost.

Things start with a pre-show scenario that allows spectators to settle not only into the theatre but also to the premise of EUNOIA, mindful that mainly people will not arrive initiated into its linguistic ground rules. Thus begins a participatory game of hangman, which (as the audience gradually catches on to) is comprised solely of a answers, such as awkward and razzamatazz, with prizes of bananas and Mars Bars. Then four cast members draw straws, to determine a sequence in individual recitations of the first stanza of “Chapter A (for Hans Arp)” while doing handstands. You will gather by now that the dancers are deeply involved in voice and remain so throughout. As they recite, the corresponding words flash behind them in a video projection. This is not an easy task and once a mistake is caught, someone on the team calls out “bad.” Each of Bök’s chapters opens with a testimony to the particular act of poetry, making the respective vowel the protagonist. However, once that tribute is done, he initiates another narrative that will carry the chapter. The first involves Hassan Abd-al Hassad, a vain, wastrel tyrant who squanders his legacy on tax and war.

In the program notes for EUNOIA, Fujiwara addresses the complexity of the poem and the impossibility of its literal transposition to movement. She arrived at an analogue:

In the spirit of Bök’s Eunoia, the movement invention is initiated from body parts that contain only the appropriate vowel. In Chapter E, the dancers initiate movement from the neck, temples, spleen and knees, and in Chapter O, the pons, torso, foot, etc. The choreography takes inspiration from the poem’s verbs and avoids the nouns. … We avoid dance conventions such as unison movement, repetition, dance steps, except in specific situations where, for example we appropriate Kathak and salsa in Chapter A and jetés in Chapter E. [Bolds added.]

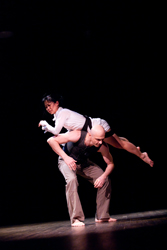

These strategies succeed to the extent that they introduce unaccustomed constraints to the company of six dancers, all highly regarded veterans: Sylvie Bouchard, Claudia Moore, Lucy Rupert, Miko Sobreira, Rebecca Hope Terry, and Gerry Trentham. (Lacey Smith, the more essential and involved-than-usual understudy in the shaping of the work, did not appear during this run of EUNOIA.) The emphasis of certain body parts frequently called attention to itself in forced patterns of imbalance, through which the dancers frequently, skilfully, stopped in loco to display their control over exaggeration. Sometimes this created very amusing freeze frames, such as one individual’s teeth clenched on the flesh of another. But often the effect highlighted the charade element of insistent signalling gesture. Likewise with the references to dance styles. The Kathak passage emerged with satisfying confluences of tabla and raga during Chapter A. However the salsa section was more a caricature, and the few steps of tap a mere squiggle.

Throughout its running time of sixty-five minutes, each dancer is onstage and up to something or other most of the time, whether at the centre or the periphery. EUNOIA utilized a broad centre stage, its floor and the backdrop frequently emblazoned by video projections. Either side of the stage was a parallel open allée in which costume changes took place, as well as sidebar, footnote activities, such as a brief pantomime of sleep. Because there was so much going on, circus-style, it is difficult to track any continuum attached to any individual. They are not characters per se, although they frequently dropped into character, à la sketch comedy. Moreover, a section of Eunoia that lends itself to narrative portrayal, such as the tale of Helen of Greece, is deliberately thwarted by substituting her various female players. As opposed to Bök’s poem, the disembodied stars in EUNOIA are the five vowels. The individuality of the dancers emerges in softball pitches to their natural talents. Bouchard mellifluously handles the phrases in French. Terry demonstrates her skill at singing. Sobriera shows his experience in commedia dell’arte. Claudia Moore is, well, Claudia Moore, a consistently elegant and angular interpreter in contemporary dance. Great showmanship, some surprise, but an evasion of the spirit of constraint that supposedly guides the artistic choices.

Following the singing is signing, as in American Sign Language, a satisfying transition both as contrast and anagram. Consequently an entire stanza is muted out. That is OK, however, as this EUNOIA is considerably abridged, with only about half of the poem’s stanzas included. This allows Fujiwara and company to handle the sections differently from one another.

The chapters and their sub-sections are strongly elaborated by costume, video projection and score. The costuming changes, which require the dancers to frequently visit the wardrobe racks on either side of the stage, with a thematic colour for each section, derived directly from the graphic design of the Eunoia publication: “A noir, E blanc, I rouge, U vert, O bleu.” Other choices within chapters conform to the basic premise of single-vowel chapters, i.e., a poncho. In general, Andjelija Djuric’s costume design and direction proves a distracting cornucopia of superfluous references, or rather the least essential shuffling of an already overloaded deck. Its dress-up tactic is, however, consistent with the strategy of preventing the performers from becoming consistent characters. The often-ravishing video by Justin Stephenson, mostly of flashing or cascading words, has an almost autonomous construction, rewarding the eyes even as one takes them off the action onstage. It is most successfully manifested at its least complicated, a pulsing mandala comprised entirely of the letter u, whipping up a surge to the galloping momentum of the brief, ribald homestretch chapter (“for Zhu Yu”). Otherwise the blizzards of words in the video segments, gorgeous though they might be, reveal the puzzle, the bewilderment, the sheer dread of so much language in the world, a notion that ultimately is at odds with Bök’s. The best execution is the sound tapestry composed by Phil Strong, which deftly intersperses wawa with tabla or mixes dobro, bongos and Moog. Strong also develops his own system, the “single black note” rule, which uniquely associates one of the five black keys of a piano to each of the five vowels. Perhaps because musical notation already has a comparable relation to music as the alphabet has to language, his system avoids contrivance and attains ingenuity and new expression on par with Eunoia.

EUNOIA is not the first choreography to tackle a freewheeling eccentricity of language. Kate Alton and Ross Manson produced The Four Horseman Project in 2007, which tapped into the sound poetry doo-wop of verbal anarchists Rafael Barreto-Rivera, Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery and bpNichol, Bök’s immediate and acknowledged predecessors, and similarly combined recitation, movement and video projection. Nor is EUNOIA alone in seeking a constraint-basis for carrying dance beyond its accustomed habits. Toronto Dance Theatre’s recent production of Henderson/Castle: voyager (February 20 to March 1, 2014), in which choreographer Ame Henderson imposed severe conditions with respect to directionality, relationship and endurance, accompanied by a pseudo-stream-of-conscious libretto by singer/pianist Jennifer Castle, skittered to the brink of failure and then triumphantly fulfilled its departure. What is most brave about EUNOIA is that it sublimates dance to a bigger idea, so that addressing the dance elements of the work is the least important aspect of writing a review. This is not because the dance was not skilful or elegant or inventive, but because it just happened. Seeking to amplify choreography to the helter-skelter pitch of Eunoia fails because Bök’s poem dares to go where dance and choreography already reside. What other art form places greater value on systems of artificial constraints than dance?

All that said, EUNOIA solidly entertains, rousing standing ovations both nights that I attended. I enjoyed the second night far more, as I set aside analysis and just followed the show. Yet even in that respect, perhaps EUNOIA does not go far enough. The voices meld into an adept, stirring polyphony. What would happen, however, if they tempted cacophony?

Tagged: Contemporary, Participatory, Performance, ON , Toronto