At first, it’s difficult to figure out exactly what is going on in MOTHER sound / body, a compilation of three short dancefilms presented by Method Dance Society, a company based in Prince George, B.C. Three young dancers move slowly in front of a shifting blue background — projections that look like the sky above an ocean. A calming, deep electronic soundscape underlines their explorative movement. One dancer extends her fingers forward, as if trying to grasp her environment.

This beginning of Mother, the first work in the series, sets the tone for the digital performance that premiered on June 15 and was available for four days. Three five-minute works by different choreographers in collaboration with Jon Russell, technical director, “explore the digital self through sound and light body mapping,” as described by their website. In practice, the dancers wear sensors on their wrists, which control the lighting, music and projections in the performance environment. The world around the dancers changes in response to the choreography, forging an interesting, almost tactile relationship between the performers and their surroundings.

Sensation is at the forefront in Mother, choreographed by Shelby Richardson, artistic director of Method. Close-up shots show the dancers experiencing the textures and fabrics around them. Their sheer trousers, muted pink long sleeves and white fabric props all become part of a porous environment where lighting, touch and sound seem to blend together. Though the choreography is minimal, company dancers Ashley Burmaster, Shayla Dyble and Sloane Zogas manifest a careful attention — at one point cradling bunched-up fabric tenderly to their chests, like children. In other moments, flickering lights and sudden moments of hesitation make the work feel like the calm before a storm.

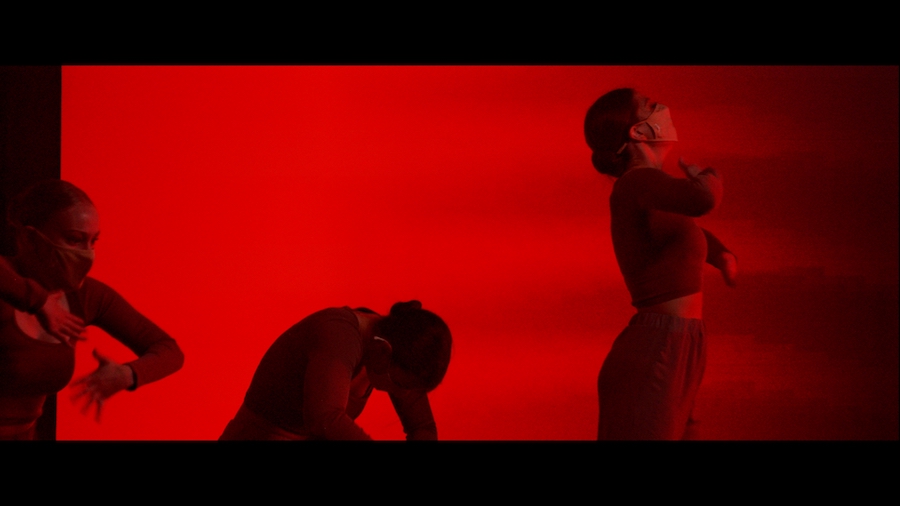

Arrhythmia, choreographed by Burmaster, is like the energetic antithesis to Mother. Three dancers (Burmaster, Kendra Hamelin and Sara McGowan) are engulfed in what looks like a red fog, moving their arms quickly between shapes, contracting their torsos and reorganizing themselves into crisp formations. Flashing lights, like passing sirens, convey urgency or desperation. Time seems to be in flux — speeding up, cutting between shots and blurring or dissolving in the middle of a phrase — which recalls the work’s title but makes it slightly disorienting to watch. When the trio becomes a solo (split-screen with the dancer’s mirror image on one side), it becomes easier to track how the lighting responds to specific movements, which is an absorbing study in itself.

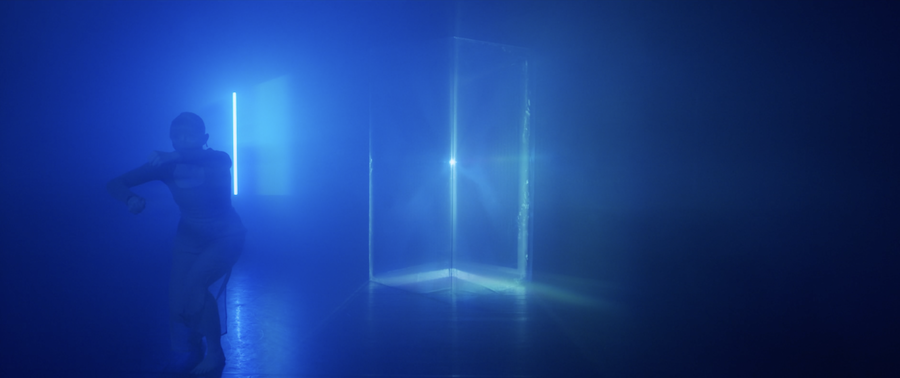

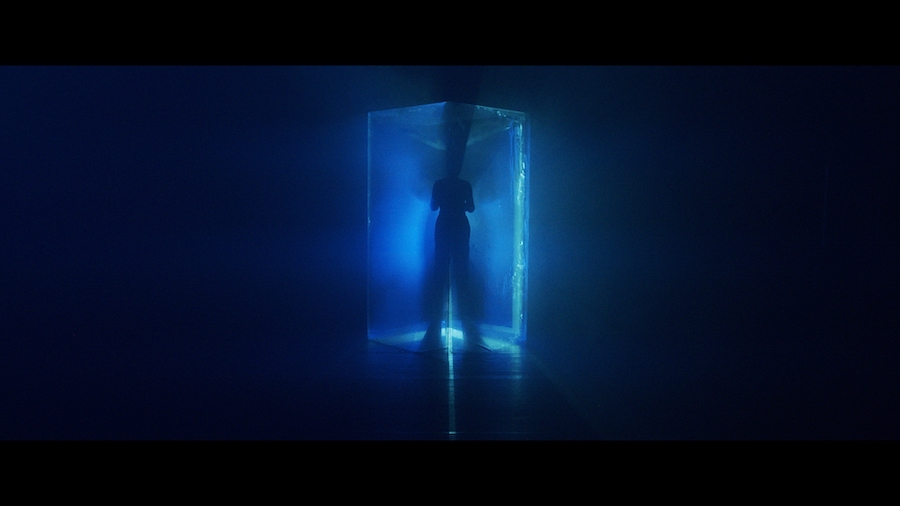

The final piece, Re-Cognize by Giselle Liu, starts with the intriguing image of a dancer walking towards a large blue prism, almost like a glass elevator, with her head cocked slightly to one side. When she places one hand on the surface, a wheel of light starts spinning behind it. Moments later, she seems to be inside, performing a rapid gestural sequence.

The work, which is described on an informational slide as exploring the “multidimensionality of our interconnected experience,” plays with the viewer’s perception. The first solo builds into a trio of fragmented choreography performed by dancers Zogas, Burmaster and Grace Perry, with elbow hits, swirling wrists and small lunges inside or in front of the prism. However, the movement seems almost like a placeholder for the larger question of what the blue object represents and how the dancers relate to it. An arresting shot near the end shows a dancer “inside,” touching hands with two dancers on the outside — perhaps an allegorical moment of connection with the digital self, or with new technologies.

Overall, MOTHER sound / body is beautifully produced, though the editing, close-ups and brevity of all three works make them feel like just the beginning of a larger story. The possibilities for what Method describes in an introductory slide as a “living, breathing performance environment” that responds to dancers almost like a co-performer seem endless.