Some Hope for the Bastards explodes onstage, ramped up with the sound and fury of a full-tilt rock show. For Frédérick Gravel, this work is a step forward with regard to size and scope: the performance took place the Monument-National theatre — one of the city’s bigger venues. This would be a good time to discover or rediscover this independent, Montréal-based, multi-faceted artist. Throughout his expanding career, there has been a push to make him the next big Québécois success story, though the razzmatazz of that pursuit seems ill-matched for Gravel’s own stated objectives. Yet, the irony of this anti-hero artist being propelled to greater heights, someone who is hardly seeking that kind of worship, can’t be overlooked.

From his earliest pieces, Gravel has always specialized in an unmistakable mix-and-match blend of music and dance. He’s always been the reliable front man for his band and his group of dancers. This time, he doesn’t dance at all, though his warm, nimble intelligence and wry sense of humour pulls in audiences. With his company, Grouped’ArtGravelArtGroup (GAG), he’s got a creative crucible, attracting engaged performers and artists for each project. The emphasis in any given work is on shifting the lens on how dance and performance are seen and appreciated by the public. Collaboration is the byword for his team of artists.

This new work begins as the public enters the enormous venue. Some of the nine dancers (David Albert-Toth, Dany Desjardins, Kimberley de Jong, Francis Ducharme, Louise Michel Jackson, Alanna Kraaijeveld, Alexia Martel, Frédéric Tavernini and Jamie Wright) are already onstage, standing or sitting, in held positions, with beer and wine bottles in hand, while others mill about and around the audience. A party seems to have already started. A single tonal sound resonates in the space, and slowly the performers begin shifting their stance, settling in for what appears to be a group portrait by gazing out onto the audience.

When the band (Philippe Brault, José Major and Gravel) arrives onstage, the pulsing electro-live music begins with a heavy drumbeat and whirring guitar licks. Then, in a brief interlude, Gravel begins his fun patter, first commenting on the somewhat empty feel in the big room. He tells us that he usually talks a lot, but not in this piece. He points out there are, in fact, two starts to the show. “We just did the first,” he notes, and then he slyly says the second will soon start, “and it’s your responsibility to choose the best one.”

Gravel himself is the beating heart of the show. He talks about the expectations of a premiere (the avant-première took place the previous week in Munich). “I’m sure you have expectations. Expectations are interesting. I’ve got expectations of you.” The audience chuckles and relaxes. He prefaces the rest of the evening, talking a bit about the title: “We’re all bastards. I don’t know how to change things,” suggesting that there’s little to do in the face of our current state of affairs. Gravel also expresses a certain guilt about this powerless position, adding that he’ll do his best. He is never didactic, but rather he taps energies of truth and beauty amid conflict, however fleeting and fugitive.

The second “opening” begins with a recorded version of the introductory chorus of Bach’s sacred oratorio St. John Passion. Slowly, surely, the dancers’ actions shift; gentle pelvic thrusting builds into a restless rhythmic accentuation of the progressions in the music. Eventually, the classical work segues with live drums, and the movement rises into the dancers’ chests.

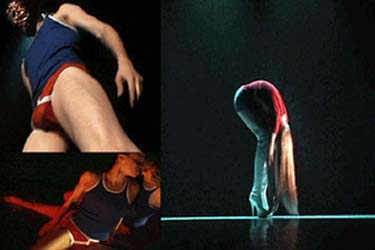

Gravel’s ensemble of dancers, dressed alternately in formal wear or jeans and t-shirts, is completely invested in the intensity and physically demanding movement, and there is no attempt to hide the sweat and exhaustion that sets in. They bang out their unison — the more “dancey” movements — relentlessly. The non-narrative piece situates them in their solos as isolated beings, edging to connection and yet burdened by an untenable human condition. Gravel seems to propose structured tasks for his dancers to engage in, with disintegration as one notable example. Even in the duets, dancers appear to reach an edge to intimacy, and in this sensuous state they seem coolly removed from each other. A gorgeous solo after the midway point cools the temperature of the piece and features de Jong alone onstage, settling into a calm and subtle sculpting of space.

The band’s hardcore stylings dwarf much of the proceedings in terms of decibels, but they also offer some of the best insights. Gravel’s modish, introspective songs (performed in English) are winning, and last night he was in particularly good voice. The songs balance a lyrical precision with a smart, desperate sensibility. “Nobody loves me,” he cries. In this “busy, dizzy” world, he suggests, we’re all passing through. Gravel displays a disciplined wit, and Some Hope for the Bastards should only increase his acclaim beyond his already devoted fan base.

~

Watching a young man incessantly jump, tap and spin, with incremental adjustments without pause over the course of fifty minutes, appears to be a simple concept. In the distinctive new work bang bang dancer-choreographer Manuel Roque is the man in question. With his toned, nimble body, he’s at the ready to jump into action.

The black walls and stark design of the Théâtre Prospero emphasize Roque, dressed in a sleeveless t-shirt, pants and running shoes, on a bare stage, as he begins a series of knee bends. With each move, we hear his breath, even and steady as a uniform beat sets the pace. The effort and the concentration demanded in his every action are evident. Sweat drips off him and pools on the floor. He introduces a little bounce, another, and then back to the bends. This sequence develops into a series of horizontal hops moving across the space. A blotch of red appears on his t-shirt. At first I think he’s bleeding, which makes no real sense. Then I see a hint of blue. Then green. It dawns on me that Roque’s radiating heat is changing the colours, and I’m watching something akin to an evolving Rorschach test.

There is something dynamic about watching this nuanced solo dance, his intention, his work with gravity and his fulfillment of the task at hand. Roque uses his body logically and intelligently, and his technique has an articulate, disciplined complexity. This piece made me think about understanding our brain at a given moment and how that domain relates to the body through unchangeable mathematical laws — a train of thought that raises questions about consciousness and how it fits into the world. Engaged as Roque seems to be in the pulse of life, he also states that he’s keen to attain an “obliteration of something human.” But I was left wondering, how do notions of disappearance and states of consciousness coalesce?

Roque’s movement grows steadier, devoid of mannerism or affectation, and he executes some mean tap dance stylings. At one point he starts to hum; it seems involuntary, as if he’s in counterpoint to or part of some overriding structure to the piece.

The sound landscape is an idiosyncratic mix of body percussion, buzzy electronica, Debussy’s Clair de Lune and a snippet of film soundtrack, all leading to an apocalyptic overload of rumbling sound. Through this, Roque dances in off-centred syncopations, incorporating internal rhythmic devices, culminating in a propulsive approach to a body moving in space.

They’re quantum leaps, literally, all those little jumps. I’ll admit physics is not my strong point, but what I’ve gleaned about quantum mechanics is that volatile particles exist in multiples states. Risky, even dangerous couplings occur simultaneously, which is a principle that Roque appears to be embracing in the embodiment of his choreography.

I once watched an episode of the PBS program Nova that probed the science of string theory. According to scientists, if we could more closely examine particles of the universe (electrons, neutrons, quarks, etc.), an ability well beyond our present technological capacity, we would find an infinitely thin rubber band, in which each particle contains a tiny, vibrating, oscillating, dancing filament loop that physicists have named a string. In a sense this finding represents the driving force of bang bang, and Roque’s pursuit of a loss of self or, more particularly, disappearance.

Brian Greene’s book The Elegant Universe embraces this very speculative arena. In reference to the “elegance” of string theory Greene says, “When we talk about theories of physics being elegant, what we often mean is that a theory is able to explain a wide range of phenomena using a very small number of powerful ideas. The elegance comes from the tremendous reach of these few simple ideas.” I’m thinking that the poetry of these theories and ideas has similarly engaged Roque’s imagination. In this way, he is shaking up and using the format of conceptual contemporary dance and pushing it to its farthest limits.

~

For Monument 0: Haunted by the War (1913-2013), the Hungarian-born performance artist, dancer and choreographer Eszter Salamon, who lives in Berlin, has culled movement from tribal war and folk dances practised across the globe during the last 100 years. These dance traditions are, of course, much older, but bracketing the time frame makes sense in relation to Salamon’s creative proposition, which is, as she states in interviews, to create an “alternative dance history,” with the idea of “recuperating dances modern dance has tried to evacuate,” or more simply put, “the history that the West has tried to forget.”

In this rare and uncompromising work, Salamon perceives and reshapes the historical experience as a repeatable one, associating its relevance to the present. The functions of war dances often link to notions of heroism, political power, control and continuity; they can serve in attack or defense as dances of resistance and as expressions of salutation, devotion and healing. In essence, Salamon’s dance serves as a compendium of many of these emblematic ideas and representations.

The piece echoes as a gateway to various movement rituals and ceremonies, but the historian in me needed more information (at least in the program brochure) about the specificity of these dances — their origin and the context in which they are danced. Wearing stylized black-and-white “dance of death” costumes, masks and makeup, by French designer Vava Dudu, dancers enact, for example, a fighter’s actions, often drawn from real combat. Characterized with a large, solid and secure grounded base, with feet widely spread apart, the dancers perform variations of deep torso and knee bends. Shoulders are used as a central movement axis with movements often involving jumping and shaking. I also noted, in sections of this procession, that the dancers’ perform complex unclassified circular dances with spins at various rates of acceleration, displaying the dancers’ agility and precise movement control.

Solos predominate the first half of the performance, but as the piece progresses, the formation of groups is dramatized. The dances appear aggressive, violent at times, though there are more peaceful renderings as well. The harmonious fusion of the dancers’ controlled body movements with their vocalizations, breath and body percussion, as well as sounds from utilitarian instruments like whistles and a bottle, was striking and occasionally, as during a clapping section, astonishing in its unifying presentation of community.

Most impressive is the transformation that her six extraordinary performers undergo, with deep shifts in tone and resonance as they move from one dance to the next. Boglárka Börcsök, João Martins, Yvon Nana-Kouala, Luis Rodriguez, Corey Scott-Gilbert and Sara Tan are totally invested in the various complex sequences, building degrees of rhythmic and physical strength, and ably displaying the energy necessary to engage in combat and war, whether in victory or mourning.

As the appropriation debate rages in this country, Salamon reveals her approach to that contentious concept in the program notes, noting its legacy as one entwined with the history of capitalism and colonization. “I do not employ [appropriation], because it leads us only to guilt and renders any form of action impossible. It locks us into impractical assigned identities.” Further, she states, “Learning the movements of others is a sensual and political act. It allows us to get beyond ourselves, to question what we have in common.” Although I appreciated Salamon’s acknowledgement of this important issue, and its relevance in her practice, it did leave me questioning the vagueness of her statement and the lack of transparency in the work itself.

In Monument 0, Salamon approaches the culturally unfamiliar through her research and process of creation. In essence, it captures these dances, rituals and the accompanying rhythms in a unique presentational envelope. She’s integrating refracted ancestral memories, not artifacts, into the here and now. In this way, she is connecting these dances in the continuum of existence of all communities and recontextualizing the experience of trauma and remembrance. Considering the world’s daily atrocities, there’s much to be valued in her response to the torment of war. Her restitution of the cataclysmic past reverberates in her ensemble and, by extension, to the audience to whom it’s being offered.

Tagged: Contemporary, Montréal , QC