6.58: Manifesto was presented at Montreal’s Agora de la danse, Sept. 15 through 18. It is available in a webcast adaptation until Oct. 2 and will be presented in Ottawa at the National Arts Centre from Oct. 6 through 8.

In her new multidisciplinary work, 6.58: Manifesto, Montreal-based, Colombian-born choreographer Andrea Peña demonstrates that we are social constructions, conditioned to submit to authority and to accept given social norms.

Set in a post-industrial reality, the piece conveys a darkly dystopian universe, where dread is omnipresent and free will has faded away. In its opening moments, an ominous rumbling and an operatic voice weave in and out of the score (terrific sound design by Marc Bartissol, alias dull).

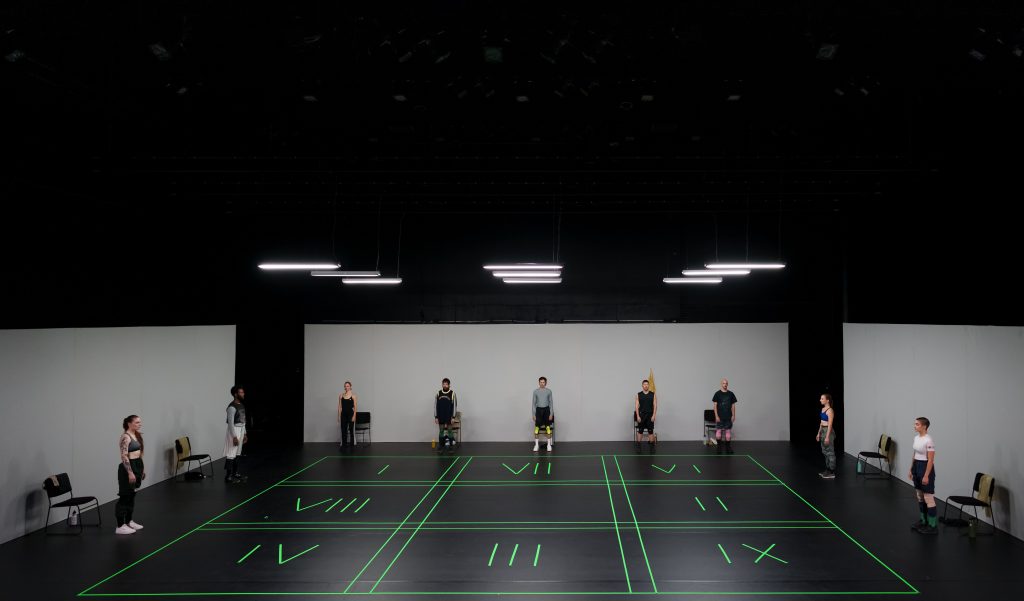

Quadrants containing roman numerals are taped on the stage floor, nine in all, clearly and proportionally laid out (set design by Peña and Alexis Gosselin). The dancers are aligned, ringing the stage, standing, waiting. There’s an accompanying film version that Peña created with an unforgettable opening, not seen in this stage version, where vacuum-sealed plastic-bag costumes are churned out systematically on a conveyor belt.

Numerous theorists have written about the development of capitalism and the politicization and mechanization of our bodies, yet I don’t think I’ve ever contemplated these concerns in alignment with a dance work.

Peña, recipient of the Banff Centre’s 2018 Clifford E. Lee Choreography Award, and a welcome choreographic voice in Montreal’s dance scene, intimates in her dance-scape that human agency is continually undercut, even if there are attempts to counteract that manipulation.

In the opening section, we hear a disembodied computer-generated code give instructions, generated live, to the performers. At least, that’s what we are told by this “voice,” and I know so little about code that I’ll believe it. “Let’s begin,” it says. A dancer’s name is then called, followed by a series of numbers. Under the glow of cold fluorescent-like lights (lighting by Hugo Dalphond), the dancers dutifully go to the spots on the floor and enact a repeated series of gestures, falling to their knees, pivoting, elbows up, repeat. We hear their breath, see their effort.

Peña works with almost militarized floor patterns, executed by the dancers with relentless, almost brutal, precision. At times, they stand and blankly stare at one another. The movements are clear, but the accumulation of the material doesn’t seem generative. When the voice asks, “François, are you at your max?” my immediate response is, what max, and who is determining the output? It feels like control through surveillance. “Remove the tape (from the floor),” dancers are told.

The work is set in three parts, and the middle section is arguably the most relatable. It’s also hugely enjoyable due to the performers’ mastery of raw dance energy. The cast pull off some of their clothing, many now topless and wearing thin plastic leggings (costumes by Polina Boltova and Rodolfo Moraga), in what can only be described as a club rave scene.

A parade of bodies, in the moves, edging through the penumbra. The gaze of the dancers (Nicholas Bellefleur, Veronique Giasson, Gabby Kachan, Benjamin Landsberg, Jontae McCrory, Erin O’Loughlin, François Richard, Jean-Benoît Labrecque, Frédérique Rodier and later onstage soprano Erin Lindsay) grounded, connected to what’s happening inside, their limbs and bodies and their palpable sweat communicating. It’s as if they are finally freeing themselves from subjectivity and freely expressing their uniqueness through their movement.

The dance is rhythmic, ecstatic, loose and dissident, and sometimes all at the same time. Sometimes dancers embrace, clinging to one another. Couples and singles dance; sometimes they seem to chug along in unison, and there’s a jauntier soundtrack, void of the oppressive industrialized pulse. Mechanization seems at bay, but while swept up in the moment, the rumbling score lurks back in, and there is ultimately little comfort. All is not well. When the sequence ends, the performers strip off their plastic garments. A sanitation man, with gloves and a plastic bag, comes onstage and collects the strewn garments.

Throughout the work, we see how Peña’s disturbing proposition develops, first with an authoritarian series of sequences that deny individual choice and where manipulation through scrutiny reveals the increased pressure and, through verbal coercion, the dictates of others in charge.

The second section, preceding the dystopian denouement, shows how dance and art, in general, can be a dangerously subversive tool that brings about awareness and arguably freedom. In a real sense, Peña’s choreographic investigation examines the body as a social body, a locus of political struggle. A site through which societies and institutions, through normalization, control, regulation and discipline, create an oppressive system that allows no space for otherness.

The third section, which has less definition and begins to meander, sees bodies in discordant movement, hunched or huddled in desperate clusters, clutching one another, appearing like survivors. Attrition sets in, and some fall lifeless to the floor. There is little optimism in what remains.

Peña’s manifesto raises the flag that art requires time, patience, concentration and mindfulness, especially in a time when most of us have become distracted, fragmented and impermeable. 6.58: Manifesto is a work for our time, fundamentally interrogating the efficiencies of science and technologies and whether these pursuits are benefiting societies in our increasingly post-human society.

Tagged: