From plaid-clad, bearded lumberjacks, to backdrops evoking Group of Seven paintings, to a monstrous whale inhabiting the waters of a Nova Scotian fishing village, The National Ballet of Canada’s Pinocchio pays homage to the country hosting British choreographer Will Tuckett. Pinocchio tells the story of a boy made of wood who must learn the meaning of being human through encounters with a swindling Cat and Fox and other individuals out to deceive him. Set to music by Paul Englishby, Pinocchio premiered on March 11.

Deviating from the non-verbal tradition of ballet, Pinocchio features dialogue written by librettist Alasdair Middleton. The Blue Fairy Shadows (Guillaume Côté, Harrison James, Antonella Martinelli, Sonia Rodriguez and Xiao Nan Yu) have speaking parts to communicate learned morals and narrative. Purists may argue that the spoken word has no place in ballet, and technically they would be right. Ballet’s intricacy and tradition of codified mime negate the need for speech; the language is inherent in the movement and the audience’s ability to interpret its meaning. However, while arguably not necessary for the comprehension of the plot, the spoken lines are, simply put, fun. They make the performance markedly different from the more conventional, and help to demystify ballet for younger or less experienced audience members.

Given Tuckett’s inclusion of the Canadian theme, perhaps it has been carried through into the dialogue. Hearing the varied accents of the dancers reminds the audience that the National Ballet is representative of the country. The company includes people from different parts of the world with their diversity in training and experience. Hearing the New Zealand, Québécois, Chinese and Spanish accents serves as a lovely reminder. Whether intentional or not, the resulting effect sends out a welcome message of solidarity.

Pinocchio succeeds in demonstrating the strength and multifaceted prowess of the National Ballet’s dancers. Despite not being vocally trained actors, the dancers transition from engaged lifts and demanding leaps to speech and chants with no hint of shortness of breath, pointing to the company’s impressive stamina and conditioning.

Tuckett has cleverly tackled the singularly difficult task of choreographing a wooden puppet to be graceful. Danced by First Soloist Skylar Campbell, Pinocchio keeps his hands and feet rigidly in position while the movement of elbows and knees keeps the steps fluid and continuous. As the ballet goes on and Pinocchio experiences humanizing events, the binding set of his hands slackens and his feet return to the classical pointed form. Rather than creating a parodic restrained range of motion, Tuckett’s artistic choices make for an animated and reasonable depiction.

Elena Lobsanova as the Blue Fairy is the embodiment of flight. Her movement meets no resistance as she effortlessly glides through turns and hovering jumps. While many of the Cat (Jurgita Dronina) and Fox’s (Dylan Tedaldi) steps move through the passé position to evoke the typified animal jump, their partnering features long lifts with beautiful leg extensions. With unmistakably jazzy influences, Dronina and Tedaldi twist, dart and weave their way through the magical spaces, truly inhabiting the sets.

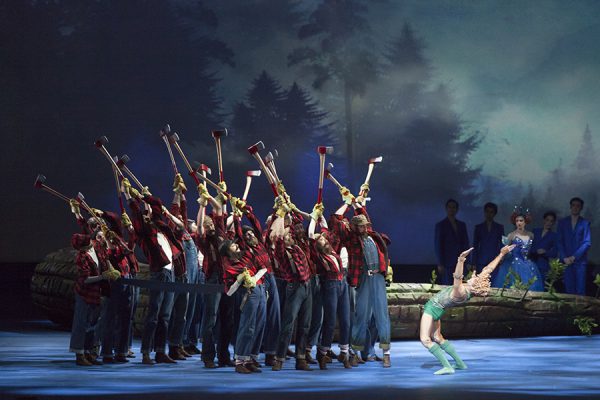

The ensemble pieces move like a single articulating body. This effect appears immediately in the lumberjacks who open Act 1, propelling their axes with expansive, arcing swings. The rising and sinking levels of cleaving and chopping are echoed in the staggered undulating of the underwater sequence in Act 2. Each dancer moves in reference to another, creating an overall impression of unity while maintaining a sense of differentiation in detail of step.

The stagecraft is arresting, even by The National Ballet’s standards. The production effectively employs technology through projections designed by Douglas O’Connell, creating an absolute absence of stasis. At times the images on the screens or backdrops seem three dimensional, making Pinocchio a highly immersive experience. Campbell, Lobsanova and Piotr Stancyk (dancing the role of Geppetto) fearlessly fly on wires, even upside-down at points. Alongside the multitude of special effects like a splitting tree trunk, careening boats and a growing nose (albeit with a mishap involving an exposed wire opening night), the company has its hands full and rises to the challenge magnificently.

The speaking will not please everybody – change rarely does. However, an audience member prepared to witness a fresh, rollicking, interdisciplinary retelling of a classic story will fare much better than one expecting a traditional ballet. The National Ballet of Canada’s Pinocchio trades in humour and excess. The effect is effervescent.

The National Ballet of Canada performs Pinocchio from March 11 through March 24 at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts in Toronto.