Surrounded by six artists, I sit on the floor of one of The National Ballet of Canada’s expansive studios in Toronto with the morning light washing over my face. It’s the end of February 2020, a few weeks before the first COVID-19 lockdowns. We are getting ready to jump into Day 1 of my new choreographic work. For the next two weeks, we will be physically investigating the impact language in health care has on the healing body. It has taken me three years of application writing, fundraising and research to get this project going. Usually, this moment is one of my favourites; we’re on the edge of diving into something new. Today though, I feel like I have nothing to give. Over the past two years, my inspiration has seeped out of my body. It’s not the first time I’ve felt this way, but it’s the first time I’m able to name the feeling: emptiness.

Fast-forward three weeks; it’s the first week of lockdown. I was meant to be nestled in a cottage, far away from the city. Instead, I’m sitting at my dining room table staring down at a chocolate cake with the number 30 spelled out in raspberries. I remember a conversation with my mother the week before. “I’m looking forward to just not caring about what other people think in my 30s,” I told her. But right now, all I can think is “Please get me out.”

During the first six months of COVID-19, I can’t escape feeling drained, like I don’t care and like I want out. But I realize that none of these thoughts are new. They are just harder to avoid now that leaving the apartment isn’t an option. I’m not running between multiple gigs in a day, trying to make ends meet. I’m no longer spending my nights cramming to get applications in on time. Most of the professional things I’ve been frustrated with the last few years aren’t there anymore. But I’m still not happy. In the stillness of COVID-19, I realize that I don’t want to be in Toronto anymore.

My husband and I had been contemplating moving away from the city for a while, but fear held us back. How would the move impact our arts careers? We didn’t know how we could live in an environment that was comforting and authentic for us while being able to work full time as artists. I was worried about becoming invisible. As I watched continuous pandemic-related closures devastate the arts sector, my worries about progress within my career didn’t seem that important anymore.

“In the stillness of COVID-19, I realize that I don’t want to be in Toronto anymore.” says Irwin.

So in October 2020, we moved to Manitoulin Island, Ont., the largest freshwater island in the world, with a year-round population of fewer than 14,000 people. We weren’t the only ones choosing to leave. In January, Statistics Canada reported that from July 1, 2019, to July 1, 2020, a record 50,375 people left Toronto and 24,880 left Montreal for smaller cities or towns. Similar trends were also reported in Vancouver.

For someone who has always identified as a “city girl,” I never thought I’d be planting roots in a small community. Within the first weeks of moving though, I notice my creative drive returning. I’m slowing down and listening more to the birds calling, the wind in the trees and the water lapping against the shore. I catch myself moving just for fun again and dreaming up new projects. As my desire to move and make work returns, I can’t stop wondering how I can be an artist outside of a big city. This thought leads me on a search to connect with other artists based in smaller communities and ask them about their experiences. What these eight artists showed me is that a fulfilling and successful arts career isn’t so much about where you are; it’s about how you choose to relate to your surroundings and how your environment can expand your definition of success.

***

Jenn Edwards and Philip McDermott were based in Toronto before they moved to Labrador City, N.L., in September 2019. Edwards, originally from Vancouver, had moved to Toronto after spending three years touring Europe with Vienna’s flowmotion dance company. McDermott moved to Toronto from Newfoundland to attend The School of Toronto Dance Theatre in 2014. After graduating three years later, he performed in various pieces including the Dora Mavor Moore Award-nominated works The Thirst for Love and Water by Sharon B. Moore and Jusqu’à Vimy by Laurence Lemieux. Despite this success, McDermott says, “It was honestly very difficult to afford rent in Toronto. I felt like I was working the joe jobs more than I was wanting to dance.” So when he was asked to run a dance school in Labrador City, he decided to make the move. “I thought it would be a good opportunity and I always wanted to move up north somewhere and teach dance to kids that wouldn’t necessarily have the opportunity,” he says. The lower cost of living helped McDermott save money, and he had more time to rehabilitate from knee surgery. The couple are now the only professional dance artists in town.

For Edwards, the move was a chance to experience something new. “I’ve never lived in a small town and I like doing things that I’ve never done. … I needed a break from the city, and it was a new adventure,” she says. This new adventure has actually made their work easier to do, especially during the pandemic.

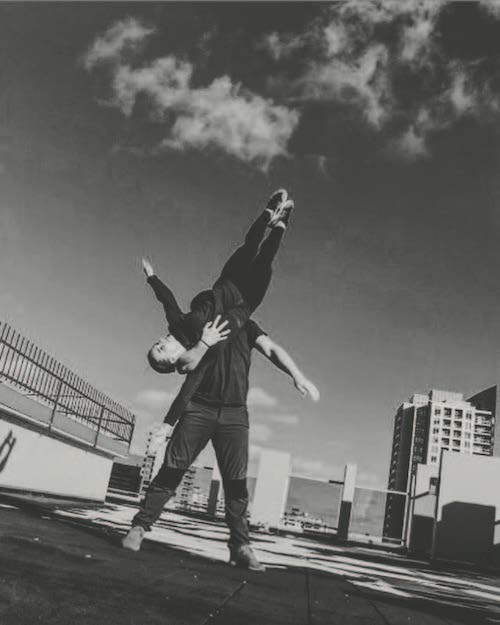

Because there have been minimal cases in the couple’s area, they can teach in person and create work together. They’ve had funding to work on a new duet called ForceField, and McDermott is developing a solo, BIGTHINGSmallthings. The couple also created the film SHIPWRECK, which won Best Experimental Film at the Experimental Dance and Music Film Festival based in Toronto and Los Angeles. Edwards describes the past year as “having a residency the whole year.”

Kristy Janvier also moved to a small town after a busy career abroad. After 15 years of performing internationally with Disney, she moved back home to Flin Flon, Man. “I just didn’t know it was possible to be a dancer in Canada,” she says. Janvier returned to Canada in 2016 to explore her roots through a contemporary Indigenous dance lens. She’s since worked with artists like Starr Muranko, artistic associate with Raven Spirit Dance, and Santee Smith, the artistic director of Kaha:wi Dance Theatre. Since moving home, Janvier has continued to create and collaborate with companies across Canada while also engaging with her local arts community. Her first solo work, Forest Floor (2017), has been presented in Saskatoon, Toronto and Edmonton. She has also toured as a guest with Dancers of Damelahamid, an Indigenous dance company.

Janvier has developed a practice that is centred around solo work, often done outdoors. This means that, other than travel restrictions, her practice has not been drastically impacted by COVID-19. She has continued to work on her independent projects and collaborate remotely with colleagues across the country. And when the pandemic has changed her plans, she’s found community support.

Just before lockdowns began, she started renting a space with fellow movement and yoga teachers for teaching and rehearsing. When COVID-19 forced the studio to shut down, they were blessed with an understanding building owner, Community Futures Greenstone, who allowed them to keep the space without paying rent. “That’s something that you only get in small communities, which is the benefit of working in a space like this rather than when you’re in the big city, you’re just another faceless tenant. When you’re in a small space, you have to build those relationships and everyone is so supportive,” Janvier says.

***

Hiromoto Ida left Tokyo, his hometown, and his acting career in search of a new relationship with nature and community. He wanted to be closer to the mountains and considered becoming a climbing guide. Instead, for more than 10 years, he worked as a dance artist in Vancouver before moving to Nelson, B.C. During his first visit to the Kootenay Region when on tour with Karen Jamieson Dance, he wrote in his diary: “This place is something. There’s something for me in this place.” For the first time, Ida could imagine himself being married and having kids. He has now been living in Nelson with his wife and two children (who are grown-up) for 20 years.

Living in Nelson has been a third chapter in Ida’s career. When he first arrived, he was a full-time stay-at-home parent and wondered if his artistic career was over. He describes those first years as being “forgotten by people.” No one called. “But then I started thinking, ‘Well I cannot die here. I have to do something,’ ” he says. So he started writing grants, even though he had never made his own work before. He now creates and performs under his company, Ichigo-Ichieh New Theatre.

On creating work in a small community, he spoke about starting from real-life experiences. Ida explains that because he knows his local community well through the interactions of daily life, he understands that the work he makes for this audience needs to start from relatable experiences. This doesn’t mean that he has abandoned his contemporary roots, simply that he has found new ways to use them. “When you live in nature, all those beautiful [lakes] and stuff, that’s so contemporary, but they’re really real,” he says.

This artistic approach has led Ida to present work not only in Nelson but also across Canada. The Capitol Theatre in Nelson is still one of his biggest supporters and main performance spaces. It’s where his most recent solo, Homecoming 2020, was presented in February through an online video screening. Ida also says that Jay Hirabayashi, executive director of Kokoro Dance and co-producer of the Vancouver International Dance Festival, is a major supporter of his work.

Five years ago, he sometimes found himself wondering about presenting in bigger cities, but he realized that this was his ego talking. This admission helped him focus on making art for people in small places, which he says is actually harder in some ways. The work, which he describes as a gift, has to be tailored to more specific audiences. “You can’t just send any gift because you think, ‘I’m good. I’m smart. I’m a good artist,’ ” he says.

Miriam Colvin also immigrated to Canada, but her reason was love. In 2004 she left Minneapolis, so she could be with her partner in Smithers, B.C. After six years of performing, creating and teaching in Minneapolis, the move to Smithers was a significant shift for her. “When we first moved here, I had that sense of just falling in love with the land. I’ve never had a garden to myself before.” But the thought of potentially no longer being an artist made her sad. “There was just this point where it actually shifted the other way of, I live here, so I better start doing my work here.”

Colvin now works under her own platform, Myriad Dance Projects. Her work is rooted in her environment and often involves collaborating with her local community. In her 2016 piece Into the Current, 75 community members were part of the performance. She is currently working on a project involving Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists called The River, which is being developed along the Wedzin Kwah River and is grounded in Wet’suwet’en authority and protocols.

Last September, through Colvin’s work with the Bulkley Valley Concert Association, three local dance artists performed Julie Lebel’s work Tricoter in a large field. “We did four performances. Maybe 50 people saw it. I just think that’s OK. I think that’s enough. I think that’s beautiful,” says Colvin, who is not interested in online presentations. “If we’re allowed to come together, even further apart, I’d rather work those logistics and hire those people,” she says.

Colvin’s community-centred approach is sometimes hard to express to her colleagues outside of Smithers. “Sometimes before I would go to the city,” she says, “nobody could understand what I was doing up here.” She wants to challenge the ideas that work should only be made for audiences in big cities or that rural audiences need to be “educated” in order to understand contemporary performance work. “The intelligence with which my work has been met and I have seen other people’s work met [in Smithers] is incredible,” she says.

Recently though, Colvin is noticing a shift in her colleagues’ perspectives. “It was exhausting to always network and always connect people to me,” Colvin says. After spending significant time trying to justify her work, she says now artists from outside Smithers are reaching out to her.

***

Christine Friday is a professional dancer, choreographer, filmmaker and community activator. She has danced across Canada for 29 years. In 2018, Friday received the K.M. Hunter Award, which recognizes Ontario artists who have made an impact in their chosen field and demonstrate an original voice within their artistic tradition. She is bringing that voice to her home community of Temagami First Nation, which includes Bear Island, and her traditional tribal family territory, n’eakimenan, which means homeland. “A big part of my life’s journey has been about moving back home. It’s been kind of what has driven me my whole life. I always felt lonely or lonesome,” she says, noting that although she hasn’t always lived there, she has worked in her community for the past 15 years. In June 2020, after three years of building a house, Friday, with her husband and three sons, finally made the move back home.

Her deep relationship with place led to her first work made since returning. Sections of the dancefilm Firewater Thunderbird Rising were shot on an iPhone by her son while the family was out on the land trapping beavers. “I felt like I’ve been able to be more spontaneous because, to me, the beauty of living in my home or on my territory is being in that present moment and having the ability to go out on the land on any given moment.”

Friday is also working on building a cultural creation centre. She has been offering summer dance camps on Bear Island since 2007, and the creation centre is an extension of this work. “It has been my lifelong dream. That’s a place that is going to help ignite sovereignty, entrepreneurship. A place that supports people to follow their true path and that relates to culture and performing arts,” Friday says. “To be able to support our Anishinaabe way, it’s really important that that space and those spaces are being carved out and made for us. And it has to come from our own people.”

Shayna Jones is also finding her own way to carve out space for her voice within rural settings. Jones is a multidisciplinary spoken word artist, performance storyteller and folklorist of Afrocentric experience. She grew up in Vancouver but has moved to progressively smaller communities. Currently, she is based in the 968-person town of Kaslo, B.C., with a dream to move to an even smaller community “tucked away in the middle of nowhere.”

Jones moved out of Vancouver because she wanted to raise her children in a context that she describes as “slowed to a more human pace that can be more in touch with the seasons and rhythms of the natural world.” Since moving, her life, as well as her work, has grown. When she lived in the city, she was singularly focused on her artistic career. “But now that I live outside of a city context, where I have to pay attention to the actual season I am in and pay attention to the growth of my children, … I have had to find ways that my art can be nurturing to my whole life and so that my whole life can be nurturing to my work.”

[Shayna Jones] is based in the 968-person town of Kaslo, B.C.,with a dream to move to an even smaller community “tucked away in the middle of nowhere.”

Though Jones’s pace of life has slowed, she still finds ways to push and grow as an artist. Before COVID-19, Jones travelled across Canada with her family to perform. Now she is focusing on adapting her performances to video formats and investing more in local grassroots presentations. She shares that this model is actually more of a challenge for her. “To take my skill set as a performer and just do it on the ground, that feels more terrifying to me than being on a stage in front of a thousand people. I can handle that. But being in a small setting with just a few people who are invested in me as a person and to give them my work is absolutely terrifying, and I know it’s exactly the road ahead.”

With thousands of people leaving big cities, what does it look like when they land in a small town? “All of a sudden, I have an ally, which is amazing,” says Candice Pike, a performer and educator in Corner Brook, N.L. Pike has been familiar with rural living since birth. She grew up in Newfoundland and Labrador and – other than a short stay in Toronto to complete a master’s in dance at York University – has always lived there. Until the pandemic, she was the only contemporary dance artist in town. But that changed when one of her students and colleagues, Josh Murphy, moved back home from Toronto.

With thousands of people leaving big cities, what does it look like when they land in asmall town? “All of a sudden, I have an ally, which is amazing,” says Candice Pike.

About her career, Pike says that she has had to be a “jack of all trades” and be able to do everything. “There aren’t other experts and you have to figure it out,” she says. This means that Pike has self-produced most shows she has done in Corner Brook. These projects often involve her doing every task from creating the work down to licking the envelopes. But since Murphy’s return, the pair have been collaborating. “It was like a huge relief and a reigniting of the inspiration,” says Pike about Murphy’s arrival. Together, they now offer dance classes and performances. In December 2020, they secured funding from the Newfoundland and Labrador Arts Council and presented Ruralesque: The Beginning, an online sharing of dance works and workshops in progress centred around their interests in rural aesthetics and filtered through the lenses of contemporary dance and burlesque. Pike is also in the planning stages of a performance that will include work by herself, Murphy and other local artists.

***

As great as relocating has been for these artists, their moves haven’t come without challenges. Even though Edwards and McDermott are making a lot of work on their own, they miss going to shows in Toronto and taking classes. “It’s really nice to have other artists around and being able to collaborate,” says McDermott.

Some of the challenges Janvier experiences are access to rehearsal space, funding options and consistent collaborators. “The videographer runs the thrift store; the person that does the lighting for the local musicals is a potter,” she says. “So everyone has dual jobs here. No one has a full-time practice.”

Jones says there’s not a lot of cultural diversity where she lives and therefore not a lot of diversity in the art that is being presented. “There’s definitely work being done to change that, but it’s nowhere like being in a city,” Jones says. One of the ways Jones is addressing this issue is through the Black and Rural Project. “This project’s intention is to give voice to Black individuals, artists or otherwise, who live in rural settings. To speak to their experience in their skin, in their setting and to share their stories of connection.” Jones has been collecting stories and weaving them into a performance work, which will be accompanied by a gallery exhibition showcasing these Black rural voices across Canada.

As I am writing this, it is three days before my next birthday. When I reflect on where this year has taken me and the conversations I’ve had with these eight artists, I see so much of my own journey in their stories. I am currently the only full-time dance artist where I live. I see my name listed as “lead” or “the dancer” on almost every project I am currently involved in. My training has shifted away from taking dance classes towards other movement practices that I can do independently. There is ample interest from my new community about what I do, but I’m having to learn a new language to explain what I mean when I say “I’m a dance artist.” I’m even more unsure how to explain to my colleagues in Toronto what being a rural dance artist means.

Yet, on my 31st birthday, instead of looking down at a raspberry-covered chocolate cake, I will be collaborating with a local photographer in a dance photo shoot along the edge of Lake Huron. I don’t sit in massive dance studios anymore. I mostly sit in forests and sometimes on the wooden floors of gorgeous 100-year-old community centres. I don’t wait for the sun to touch my face through the windows. I run outside and it surrounds me. I am busier with artistic projects – both locally and internationally – than I was a year ago. I also have more time, space and fulfillment in my life.

I realize that my feelings of invisibility in the city didn’t mean I wasn’t seen; I simply didn’t understand how I wanted to be seen as an artist. My perspective has shifted, a lot like Edwards and McDermott in Labrador. “A combination of being here and COVID has definitely blown open what it is to be a dance artist,” Edwards says. “It doesn’t necessarily mean you have to be in class every morning, or you don’t necessarily have to be attached to any particular version of the dance scene to be a dance artist. It doesn’t matter where you are. You’re always filtering the world through that artist lens.”

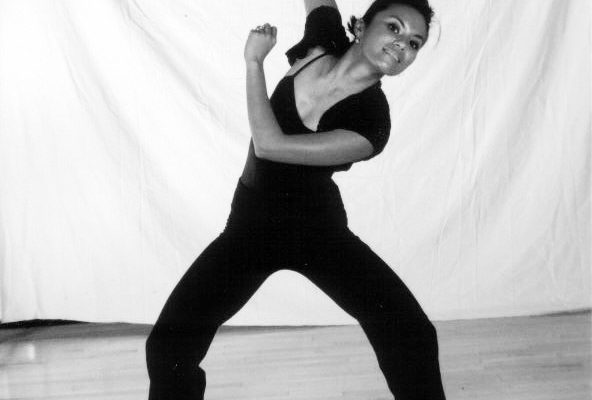

Candice Irwin (she/her) is a QueerManitoulin Island-based dancemaker, producer and educator.

***

Sommaire

En octobre 2020, Candice Irwin et son mari ont déménagé de Toronto à Manitoulin Island. Après des mois en manque d’inspiration, Irwin s’est rendu compte que ce n’était pas seulement sa carrière de danseuse professionnelle qui l’épuisait ; c’était la ville même. Et elle n’était pas la seule à s’en rendre compte… En janvier, Statistiques Canada a rapporté qu’entre le 1 juillet 2019 et le 1 juillet 2020, un nombre record de personnes ont quitté Toronto (50,375) et Montréal (24,880) pour s’établir dans de plus petites municipalités. Une tendance semblable a aussi été rapportée à Vancouver. « Je me suis toujours identifiée comme urbaine et je n’imaginais pas que je m’installerais dans une petite communauté. Mais dès les premières semaines après le déménagement, je retrouvais ma motivation pour créer », observe Irwin. Elle se demandait comment être une artiste à l’extérieur d’une grande ville, alors elle a communiqué avec des artistes d’une part et d’autres du Canada établi·es à l’extérieur des grandes villes. « Ces artistes m’ont appris qu’une carrière en arts nourrissante ne tient pas tant à l’endroit où l’on vit, mais plutôt à comment l’on choisit d’être en relation à notre environnement, et à comment cela ouvre notre définition de la réussite. »