When I was first starting out as a professional dancer, I worked with a dance company that some friends and I had created called Girls Only. We performed in sporting and commercial events, fashion shows and birthday parties in Vancouver. At this one particular gig, we were doing a sort of hip hop fusion/jazz funk performance at an outdoor event. We were having the best time ever onstage, when, all of a sudden, in the middle, I just blanked. I was, of course, right in the front, dead centre, when my mind went completely blank. All I could do was laugh hysterically, scream, ‘Ahhh!’ and, for some reason, I started running on the spot. Fortunately, I didn’t throw off the other girls from the show with my running and screaming. Eventually I just ran to where I was supposed to go to next and jumped right back into the choreography. I remember thinking to myself, ‘Whatever! This happens all the time! People forget all the time!

– Faye Rauw, Co-Founder, Sprouts – Growing Bodies & Minds

Almost every dancer has experienced “blanking” at some point in their career, forgetting a known section of choreography during performance. Despite hours of practice and rehearsal that deeply integrate intricate movement sequences into their memory, sometimes a dancer “just blanks” and is forced to improvise until they can recall the next sequence. What happens when a dancer forgets their choreography? How is it that dancers are able to remember intricate sequences in the first place? And, what is the science behind memory?

According to Bettina Bläsing and her colleagues in the Neurocognition and Action Research Group at the University of Bielefeld, in Germany, “The complex movement sequences executed by dancers epitomize the human capacity for sequence learning.” As a dance education researcher pursuing my doctorate in education at the University of Ottawa, I am interested in how learning and memory processes are experienced by teachers and students in the dance classroom. To further explore the relationship between memory and movement, I spoke with nine professionals working in a variety of genres of dance at various levels in Canada. While they agree that repetition is essential to retaining choreography, they demonstrate the importance of a well-rounded teaching approach with their diverse and layered learning processes, including verbal cues, mental imagery and kinesthetic experiences. Learning and remembering are closely connected, and dancers seeking to enhance their movement recall should focus not only on techniques for retrieving movement but also on techniques for encoding it into their memories.

THE SCIENCE OF MEMORY: STAGES AND PROCESSES

The most basic definition of memory is the interrelated processes of taking in, storing and retrieving information. Memories are the result of learning, which is changing a behaviour due to an increase in knowledge, skills or understanding, and are created in stages. First, an individual experiences stimuli – what they see, smell, taste, touch and hear – through their senses, and those perceptions become immediate or sensory memory. From this abundance of unclassified sensory memory, relevant information becomes working memory through the process of encoding, whereby it is assigned meaning, allowing it to be recalled later. Finally, information that is found to be necessary for future retrieval becomes long-term memory through consolidation, during which recent memories are differentiated from older ones and are made less vulnerable to being forgotten. Once they have been perceived, encoded and consolidated, such long-term memories may be retrieved for years or even a lifetime.

There are two forms of long-term memory. The first is explicit or declarative memory. It stores facts, events, people, places and objects. The second, implicit or non-declarative memory, retains perceptual and motor skills, such as riding a bike or typing on a keyboard. In order to retrieve explicit memories, such as the names of past prime ministers, the individual must be consciously aware of the process of retrieval. Implicit memories, such as driving a car, are expressed through performing a physical act without consciously reflecting on that performance.

MEMORY ON A CELLULAR LEVEL

Professional tap dancer Tasha Lawson describes her process of learning choreography as one of “embodiment on a cellular level.” For her, learning and remembering movement sequences involve complete integration so that the movement “lives” in her body’s “muscle memory.” This understanding effectively reflects the neurobiological processes associated with the encoding, consolidation and retrieval of memory.

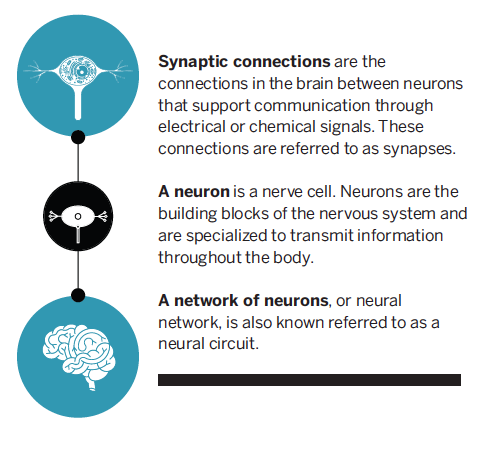

Information perceived and learned through the senses is carried through the body to the brain by sensory neurons. As information is learned, it is carried across synapses, the connections between nerve cells, through neurotransmitters and electrical signals. These transfers result in cellular modifications across networks of neurons. Remembering or retrieving reactivates these neural networks, thereby strengthening the synaptic connections and making recall easier. Current research suggests that the more memories are destabilized and re-stabilized in this retrieval process, the more integrated into the cellular architecture and implicit the memory becomes. The old saying “practice makes perfect” bears weight – the more we revisit a memory, such as performing a plié, the more we strengthen the neural connections of that memory and the more deeply we integrate it into our bodies.

LEARNING AND REMEMBERING MOVEMENT

As a dancer learns a new piece of choreography, they create both explicit and implicit memories. Their own experiences and the communications received while learning are encoded in the dancer’s explicit or declarative memory. The sensorimotor information – the sensations of performing the movement through the body’s motor functions, often referred to as kinesthetic information, is stored as implicit or non-declarative memory. Each time the dancer repeats a movement or mimics the movements of a choreographer, this information becomes more deeply anchored or consolidated within the implicit memory and no longer requires as much of the dancer’s conscious attention to retrieve it.

As both explicit and implicit memories are used when dancing, the ease with which movements are learned and remembered is highly dependent upon how structured the movement sequences are. Structured dance forms are those based on a defined set of body shapes and movements, with commonly accepted names, such as those in ballet. Unstructured dance forms, like contemporary dance, have an infinite number of possible shapes and movements, and very few of them are associated with a common terminology. The more structured the dance movements are, the greater the ease of encoding and retrieval.

In a structured dance form, movement patterns have already been committed to memory and associated with specific terminology. The processes of encoding and consolidation have thus already begun prior to learning that particular work. The synaptic connections between the networks of neurons associated with the movement are already in place and need only be strengthened and associated with that choreography. This makes the process of retrieving easier because a dancer needs to simply associate the existing memories with the particular choreography for recall. Because not all movement sequences derive through structured dance forms, even within a particular genre, dancers must access a variety of learning strategies and techniques in order to physically and mentally encode, consolidate and then recall choreography.

TECHNIQUES FOR LEARNING AND REMEMBERING CHOREOGRAPHY

Ruth S. Day is a professor in the department of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University in the United States. There she leads the Memory for Movement lab, through which she explores the relationships between remembering and dance.

Day has found that dancers use three basic types of cues to remember movement: words, visual images and movement-based cues. Words include assigning names for movements, such as step, kick, touch; counts, such as one, two, three; and non-words, such as scatting, dee-doo-dah. Visual cues might be video recordings of the dancer or choreographer performing the movement, or they might be mental imagery clues given by the choreographer or dancer to describe particular movement qualities, such as “walking on hot sand.” Movement-based cues include the musicality or rhythm aspects of the movement, the feelings of the movement and the kinesthetic feedback received while performing the movement. According to Day, there is no right or wrong strategy for remembering choreography, but there are certain situations where particular strategies work better than others.

VERBAL CUES: WORDS, COUNTS AND SCATS

Verbal cues are used extensively by dancers in both structured and unstructured dance forms. Avinoam Silverman is a former second soloist with The National Ballet of Canada (NBoC) who has since graduated from NBoC’s Teacher Training Program and now teaches ballet and contemporary dance in the Greater Toronto Area. Words are important to remembering a structured dance form like ballet, he says, because “All ballet is just the repetition of the same kind of movements, and all choreography is basically repeating a lot of movements that you have done but in different sequences.” For Silverman, ballet terminology creates a type of underlying script, where “In the beginning, you are probably thinking a lot more, so you have to go, ‘Okay this step, now this step.’ You are saying it in your head or even with your voice as you do the moves.” By learning this verbal script, it is easier to learn, retain and recall ballet choreography, particularly when the implicit, non-verbal memories have not been established.

For Marie Claire Forté, a Montréal-based experimental dance artist who performs both “written movement and spontaneous movement creation,” memory in her unstructured dance works is facilitated by putting names to movements. When she danced for contemporary dance artist Louise Bédard, for example, Forté explains that because the choreography was so “intricate and lusciously complex,” she notated each minute movement according to the initial mental associations she made. For this and other works, Forté then writes out and rereads paragraphs of movement sequences out loud. For her, this act of reading becomes a form of rehearsal in itself.

Verbal cues are also extremely important for tap dancers. Everett Smith is a professional tap dancer, a top four finalist on season two of CTV’s So You Think You Can Dance (SYTYCD) Canada and now a teacher at his dance studio, Bringing Tap Back, in Kitchener, Ontario. When teaching, says Smith, “I make my students talk tap.” Calgary-based Lawson, a former tap and contemporary dancer with Tapestry Dance Company, and the founding artistic director of the Tri Tone Rhythm Ensemble and the international festival Rhythm Body and Soul, agrees. “I feel,” explains Lawson, “if you can say your step – brush heel shuffle step heel shuffle step heel dig – count your step – a one and a two and a three and a four – or scat your step – sha-dee-ga-doo-dee-ga-doo-dee-ga-doo-ba – by the time you go to stage, when you have that moment that you start to fall out of being present and make a mistake, one of those areas is going to kick into your head and you’ll start saying or singing it, and you’ll be able to pull yourself back into the choreography and the mistake won’t be as obvious.”

VISUAL CUES: VISUALIZATION, IMAGERY AND VIEWING

Choreography is also remembered through a combination of visual cues. Sanjukta Banerjee, a doctoral student in dance at York University, instructs expert and novice students in bharatanatyam and mohiniyattam, two highly structured forms of Indian classical dance. Instruction for bharatanatyam movement emphasizes the visualization of geometric patterns, lines and shapes that are created as the body moves through the positions of the form. Mohiniyattam focuses on the formation of circular, figure-eight patterns with the body. In both forms, choreography represents traditional Indian stories that the dancer tells through her movements. Banerjee says that she focuses on the narrative aspects of her choreography and visualizes the concepts she is communicating through her body in order to remember complex movement sequences.

Similarly, for Smith, in tap and other genres, connecting the movements to a storyline aids in retention and recall. One of the most challenging aspects of Smith’s time on SYTYCD was to quickly learn and retain choreography from a broad range of dance styles. For him, “feeling” the choreography meant connecting with the imagery and story, in order to understand and remember, especially when he was working in a genre of dance with which he was less familiar, where he was unable to rely on a pre-existing knowledge of the form’s structure. Connecting with the mental imagery given by the choreographer to associate with the movement allowed him to recall choreography with ease.

For teaching competitive jazz and tap dance students, and for public school students, educator Natalie Tessier uses imagery and video recording to enhance their understanding of movement concepts and choreography. For example, when she teaches younger students how to change directions, as in a pivot turn, she says, “I tell them to imagine that they are stepping forward and squishing a bug. You really gotta push up on the balls of your feet and say, ‘Squash,’ so that you can face the other direction. With younger kids, it is all about visualization – they have to be able to relate to what you are trying to teach them.”

At Elite Dance Studio in Kanata, Ontario, where Tessier is the artistic director, teachers regularly video record choreography so that competition dance students can watch both themselves and their teacher as they practise at home. Physically following along with the video as they view and review their choreography provides students with a visual reminder until they become more familiar with the movement sequences and no longer need cues.

KINESTHETIC CUES: MOVEMENT, MUSICALITY ANDBODY AWARENESS

Movement-based cues, such as musicality and body awareness, are valuable kinesthetic aspects of choreography that aid in retention. As a hip hop dancer currently on tour with The Next Step: Wild Rhythm Tour, Trevor Tordjman feels that connecting the rhythms of the music with the movement is key to remembering choreography. For him, the choreography develops a relationship with the music so that the music literally speaks the choreography to him. When he teaches others, Tordjman emphasizes connections between particular accents in the music and in the movement to help dancers understand where they fit.

Ottawa-based bboy Sami Elkout sees a similar relationship between music and movement. After more than ten years battling and performing in breaking competitions, in 2011 Elkout opened The Flava Factory, a studio that seeks to make street dance more accessible in Canada’s capital city. For him, memory retention in the unstructured genre of breaking is less about remembering choreography and more about retaining basic movement patterns and concepts through repeated practice, and then performing those concepts with varying dynamics to a broad range of music. It is, therefore, an understanding of the musical structure and form that is most significant. “You have to really listen to a lot of different kinds of music,” he says, “so that you can anticipate the moments in the music that fit with the movements. You are not really asking yourself, ‘What are the movements?’ You have just practised them so much that they come up because you are riding that rhythm and your body taps into that muscle memory and is like, ‘This six-step pattern on this type of cadence will really match this song.’ The music determines what kinds of movements you do.”

Moments in breaking when the dancer is “riding that rhythm” and their body “taps into that muscle memory” demonstrate how learning and remembering dance movement involve the interaction of explicit and implicit memory. As the breaker learns and practises movement and choreography, neural network connections between explicit memories – the music – and implicit memories – the movements – are strengthened so that when it comes time to perform, the breaker’s implicit memories of movement are drawn out through their explicit memories of music.

Creating structures through which to draw up kinesthetic memories was also key to retaining and remembering choreography for former professional jazz and contemporary dancer Faye Rauw. Rauw, who now runs movement development programs at Sprouts – Growing Bodies & Minds in Toronto, suggests considering each step of a choreography as purposely linking to the next, “like the beads on a necklace.” Rauw therefore considers the physiological purpose of each movement when she approaches learning new choreography. Movement sequences logically flow together based on where her body needs to be at any given time.

Tapper Lawson relies on spatial and bodily awareness when learning choreography. Rather than thinking about her feet, Lawson considers the directional patterns and changes in space so that she is able to reverse the choreography with ease. Lawson also attends to the rhythmical aspects of choreography to register key “memory points” or “landmarks along the way,” linking the music to the rhythm and flow of each movement sequence. Because her approach includes speaking, counting and scatting of steps in addition to the spatial and rhythmical aspects of movement, Lawson feels that she deeply “integrates choreography on a cellular level” so that it “lives” in her body and is accessible for longer periods of time.

PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT – OR ALMOST!

Despite hours of rehearsal and practice, mistakes do happen. Disturbances in memory, or forgetting, can happen when strong emotions or prolonged stress cause the nervous system to secrete hormones that affect how our neurons communicate with one another. Describing a situation when she forgot choreography, Lawson suggests that because of an “inability to be present,” due to emotional stress, she could not recall a piece of choreography that she had considered well-rehearsed and practiced. This can also occur when we are bored or understimulated. For Rauw, it happens most often when “you are most familiar with your choreography and you don’t have to think about it anymore,” she says. “All of a sudden your mind starts wandering and you lose focus.” Tordjman sees forgetting as a completely natural part of performance. Instead, he focuses on quick and effective responses to inevitable memory lapses. A similar emphasis on “getting back into it” and “picking it back up” was repeated by all of the dancers and educators with whom I spoke.

Among the many strategies and methods, repeated practice was seen as most important to retaining choreographic sequences. Repetition, however, was understood in a variety of ways: “going over the steps,” “imagining myself moving in my head,” “watching choreography,” “marking choreography with the music,” “doing drills” and even “reading it.” Fully learning, retaining and remembering choreography is about integrating it into the body to the point where, according to Silverman, “your muscles remember.” Verbal, visual and kinesthetic strategies for learning and then recalling dance movement sequences and choreography had to be accompanied by physically doing it. Lawson suggests that a complete, physical integration implies that “the work is in the body.”

While the integration of memory is, indeed, a full-bodied experience, it is ultimately only part of the process of performing dance. All of the dancers agreed that remembering steps is never as important as the performance experience itself. As researcher Day said in an interview, remembering is a tool but not the goal. Instead it is something to be used, to “get past the learning and worrying about it – to do the movement well and enjoy it.”

This article was originally published in the November/December 2016 issue.

Tagged: Ballet, Breaking, Contemporary, dance science, dance science, Education, learning, Tap, All