Editor’s Note

Since commissioning this piece by Kathleen Smith in the spring, and its publication this summer, the public discussion of the role of the dance critic has continued, fuelled by interventions by the artists of FTA in Le Devoir, Madison Mainwaring in The Atlantic, responses in Dance Magazine and further participation by both Martha Schabas in The Globe and Mail and Peter Chin on social media. This conversation combines several important threads about the immediate economic, social and cultural forces that shape how dance is created, presented and received by its audiences. Smith quotes Holly Harris, dance and music critic for the Winnipeg Free Press, as saying, “there is a big difference between reviewing and critical writing.” Smith’s own piece brings an excellent critical lens to contemporary issues in dance criticism in Canada, but with implications further afield. We hope you enjoy this feature article, published online in full. ~ Lee Slinger

This past spring, a small kerfuffle broke out in the normally placid Toronto dance community.

In April, Toronto Dance Theatre (TDT) presented a double bill of new choreographies for its company dancers: the short works Making Belief by Susie Burpee and Returning Empathis by Peter Chin (both subsequently nominated for 2015 Dora Mavor Moore Awards for Outstanding Choreography.) The first review of the works to appear was by The Globe and Mail’s relatively new dance critic Martha Schabas. Schabas, who is an author and has a background in ballet and modern dance, wasn’t warm toward the Chin piece, which deals with themes of acceptance and reincarnation and utilizes a blend of Southeast Asian and contemporary movement vocabularies. Schabas remarked that “Chin works from a palette of Southern Asian … movement” and that she “recognized bits of kathak and (maybe) Kabuki” (the review has since been edited). Chin denied these influences with a rebuttal via The Globe and Mail’s comments mechanism and a Facebook thread inviting further discussion.

Initially, Chin was most concerned about Schabas’s choice of terminology in describing his work and what he thought it suggested about her knowledge base. “I here take the opportunity to question Martha Schabas’s value as a dance reviewer,” said Chin, “in an increasingly multi/intercultural Canada. I sincerely believe that she has taken us back decades with a worrying lack of experience and simpatico with non-Western modes of understanding and knowing art.” Chin – who has been making work for the better part of three decades – was enthusiastically supported by Facebook friends and commenters for the remainder of the TDT run, though his own comment remains solitary at the bottom of Schabas’s review on The Globe and Mail online.

Another somewhat negative review of Returning Empathis by veteran dance writer Michael Crabb appeared a couple of days later in the Toronto Star. Crabb has long been sensitive to culturally diverse work, including Chin’s, yet the artist’s response included an open letter on Facebook inviting Crabb not to review any of Chin’s work in the future.

“Michael,” Chin wrote, “as an artist, I am continuously called upon to question my own practice, and the parameters of the art form under whose banner I work. An often-used phrase is ‘pushing the boundaries.’ Why haven’t we asked this of critical writing about dance? … I dare say that the state of the practice has been coasting for too long … allowing individual critics to remain largely unimpeachable in a kind of ivory tower. Admittedly, I have had a part in the collective creation of that mirage.”

And with that, Chin articulated the idea that all aspects of reviewing dance, not just those dealing with cultural sensitivity, should be up for reassessment.

“I’m not trying to be prescriptive,” Chin told me once the dust had settled. “But because of where I’ve reached with my work, I really felt compelled to say something [to Schabas]. I was also thinking about the community at large; it’s a culturally diverse community that needs some responsible critical response as well. As for Michael, I’m not burning a bridge, I’m just saying ‘you don’t need to write about me,’ give the space to someone else … I’m not huffy and puffy about it, it’s just practical.”

Practical for Chin perhaps, but seen through a larger lens, it’s not practical at all. Crabb and his editors, in trying to comply, would have to write around Chin when he appears on a double bill, for example, or in a festival with other artists, which is no simple task. And is it even reasonable to ask another member of the dance community (which Crabb arguably is) to step back from the responsibilities of doing their own job in the interests of, well, what exactly?

Although in Toronto’s small and insular dance community, “Chingate” seemed more like an elegant snit than a community call to arms, it is reminiscent of some other high-profile dance artist/critic showdowns – Tere O’Connor and Joan Acocella; Bill T. Jones and Arlene Croce (both around reviews that appeared in The New Yorker) – in which artists have taken public exception to the way their work was reviewed or described. Dance doesn’t often rise to the occasion the way the theatre community in some parts of the world (including here) does. The theatre scene is more inclined to organize discomfort with the critic/artist paradigm by not inviting critics to opening nights, as Factory Theatre in Toronto has been doing with its current season. Or, famously, in locales like Stratford, Ont., or in the UK in London’s West End, banning certain writers deemed unfriendly or unduly biased from the theatre.

These kinds of skirmishes make fine talking points but are generally quickly forgotten. However, in the process of speaking with colleagues about the Chin response, it became clear that the community wanted to talk about the current climate for discourse in Canadian dance.

Why write about dance and how?

Most of us agree that critical discourse is an important element for art of any discipline. As Montréal-based dance writer Philip Szporer puts it, “eliciting thoughtful response and critical perspective that is not attached to the artist is fundamental to a healthy environment.” But what does the kind of discourse we support or undertake say about us as a community? What does it say about our values and our collective hopes for the future?

“Any kind of serious commentary in the mainstream press has diminished over the years,” says Szporer, who has been writing about dance for decades. He’s not the only one who thinks this kind of poverty of regular discussion and commentary is especially dangerous for dance with its already marginal status. “The curious person, or the person who might stumble onto dance, can’t get any information,” he points out. “Their curiosity can be piqued by a well-written preview or review but we’re not getting that input as much anymore. And those are the people we want to get into theatres.”

But is it the job of dance writers and reviewers to also get the bums into the seats? Maybe. With much of theatrical dance in an attendance crisis in most parts of the country, no one who cares about dance can completely ignore the problem.

When I asked Holly Harris, dance and music critic for the Winnipeg Free Press, about the role of mainstream dance reviewers, she said: “We reflect what we see onstage and to the readers, who may or may not have been at the show, by engaging with the art form as a writer. Arts writers are conduits I think. But, it’s also to provide a public record, for posterity – that’s a more pragmatic element, especially given the temporal aspect of dance.”

Despite Chin’s fears about her lack of understanding, Schabas is actually excited about the learning curves that lie ahead in her role covering dance in Toronto and is attending as much performance as she possibly can in order to familiarize herself with the complexities of the local dance scene. “As a reviewer, I feel it’s my role to be an advocate for dance. I have a responsibility to the artists but also to the public who want to have some kind of consistent barometer to depend on in terms of critical perspective.” Schabas and her editors at The Globe are consciously appealing to a broader demographic than just dance aficionados, anyone in fact who is interested in ideas about culture and society. She cites dance historian Jennifer Homans and The Guardian critic Judith Mackrell as inspirations and writers who emphasize context and try not to divorce dance from its larger political and social connections.

“I feel like dance is often severed from intellectual discourse,” Schabas says, “and that’s one of the reasons why The Globe was eager to give me a chance to write dance criticism; I have a background in literary theory. I want to think about the relationship between prose and dance and make the writing of dance interesting in and of itself.”

Who gets to write about dance?

Though most of the established dance writers I spoke to denied it, their perceived authority and influence within the dance milieu remains real. For the time being at least.

“We are part of the dialogue I think,” says Harris. “Writing about the arts is not about power, it’s about purpose. Sometimes that gets a little bit blurred.”

Schabas cites that old cliché “a bad review can be good publicity,” but believes responses such as Chin’s are “very problematic because it makes that critic seem disproportionately more important than he or she actually is.”

Meanwhile, Crabb completely downplays the impact he has within the dance milieu. At least when it comes to reviews. “If something is truly good it is going to defy criticism and a bad review from Michael Crabb is not going to make an iota of difference,” he says. “At the end of the day, it’s just one night, one opinion, hopefully well-informed. It could be right or wrong or somewhere in between, but it’s just one opinion.”

In response to less coverage in mainstream media, the dance community (to some extent) has made efforts to handle its own mechanisms of critical or analytical discourse – via online review portals such as Plank Magazine in Vancouver or by soliciting peer testimonials and responses (as Chin eventually did on Facebook for Returning Empathis). Bloggers such as Catherine Viau (Le danseur ne pèse pas lourd dans la balance) or Sylvain Verstricht (Local Gestures) provide observations on both shows and on issues in the dance world, but without necessarily or always getting into actual reviewing. Many engaged dance artists with ideas to share write, but they may not be persuaded to review. It can be tricky to critique friends and colleagues publicly when so much of the ecology depends on goodwill and mutual support.

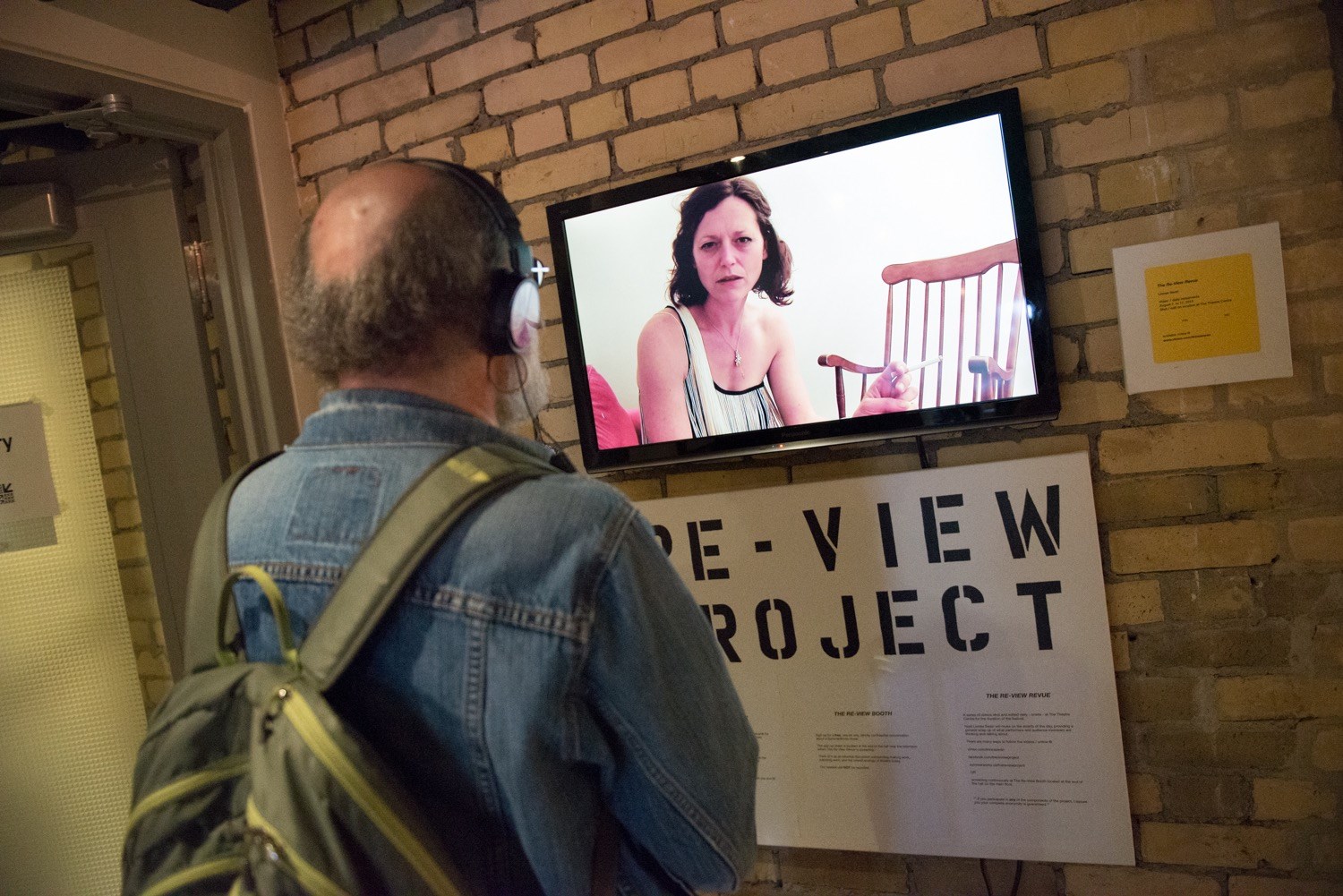

Artist Linnea Swan faced the performance community’s shyness about the review process head-on with an interdisciplinary installation project for the 2014 SummerWorks Festival in Toronto. The Re-View Project solicited critiques and impressions from artists and audience members in modalities ranging from anonymous comment cards to one-on-one interview sessions with the artist. Swan – who is best known as a dancer – also grappled with the distress around critical commentary in a series of biting and funny videos. “I started the project with a sense that audiences weren’t willing/able to articulate how they felt about a show,” she told me. “And with a growing suspicion that this silence was an indication that they are in fact losing the ability to even know if they liked something (or not), and were looking to how others felt about the work (fellow audience members, critics) to decide if they thought it was ‘good.’ The project was designed to encourage people to reconnect with their instincts and take ownership of their opinions.” Swan says she also wanted to undertake this work in a less loaded atmosphere than the one that surrounds the discussion of negative newspaper reviews.

Like Swan and others I spoke with, I believe that the idea of a multiplicity of voices and critical perspectives is one that should be encouraged. But, inviting everyone who has the time and inclination to formulate the discourse can lead to mediocrity. Nudged by artists and publicists desperate for profile and better attendance figures, writers without much in the way of critical credentials are stepping up to the plate, and, too often, disseminating misinformed commentary and shallow or thoroughly biased analysis.

“I’m having more and more conversations about generational differences,” says Harris. “I’m noticing more its impact on individual expectations. I think because it’s such a different world now and everything is so instantaneous with the Internet, some people feel they don’t have to pay their dues. When everyone is a critic that’s a problem to me.”

Those generational differences are real and based at least partially on developments in communications technology that level the playing field between publication and making public. Broadly speaking, respect for the authority of institutions such as daily newspapers and network television has eroded. But with so few voices advocating for dance in the larger public, can we really afford to dispense with the ones we already have in place? Maybe the answer is to amp up, expand and augment what has already traditionally been there for dance.

“I think the principle that [Chin] is putting forward is part of a larger discourse that needs to happen in the dance community,” Szporer says. “We’ve seen it in the visual art world, where the writers are more understanding of an artist’s work via studio visits, etc., and there’s a healthy dialogue back and forth. If you don’t have any of these kinds of discourse, what do you have?”

What happens next?

New technologies have completely changed the way we share information and communicate with each other. Even academia – that other arena of discourse and analysis – is changing. Along with specialty magazines such as The Dance Current and Dance International and other niche publications, it may be the best hope for a thoughtful analysis of ideas in dance. Artists’ expectations of mainstream media may simply be too high and they may not be looking in the right places for the coverage they desire.

“I think there is a big difference between reviewing and critical writing,” says Harris. “And I think it’s the difference between reporting and analyzing. You need both kinds of writing and it depends largely on which publication you’re writing for and what their needs are.”

Most writers for the dailies turn their reviews in overnight, writing based on immediate impressions late at night and under pressure. “Real criticism takes time for reflection,” admits Crabb. “And that’s something that a newspaper reviewer doesn’t have.”

The other thing the newspaper reviewer doesn’t have anymore is much in the way of space. Long-form critical writing isn’t an option when you’re confined to 600 to 1200 words (as Schabas is at The Globe and Mail; some of us who write for weeklies have half that).

“At the Winnipeg Free Press we used to have a lot of dance coverage,” adds Harris. “Now it’s more of a numbers game. If there aren’t going to be 300 to 400 people in the audience, chances are it will not get covered. There’s a hierarchy: ballet gets whatever they want, but that is about it. I’m not comfortable with that; it’s not enough. But I’ve heard very little in the way of complaint from the dance community – and that surprises me.”

I can’t say that the lack of advocacy or outrage really surprises me. It’s rare that anyone from the dance community adds a public comment when they disagree with the way their work or the work of colleagues is described or reviewed in a newspaper or online. Public arguments, discussions and conversations break out all the time in other disciplines, but aside from the odd Facebook thread it rarely seems to happen for dance, even when an artist like Chin bravely sets it all up for us.

If dance artists feel they have a stake in the discourse around their art form, shouldn’t they participate in it? The reality, of course, is that frank discussion can be uncomfortable, and even dangerous, within a system that is so enclosed. The possibility of blowback in the form of denied grant funding (it only takes one passionate detractor on a peer-review granting panel to derail a funding request) or a lost employment opportunity is real. But, in the long run, is timidity ever really any safer than speaking up?

The old paradigm of select authoritative voices controlling the discourse around dance is changing. It’s a moment to get excited about discussing and shaping what comes next. But I love that weird old cautionary expression about “throwing the baby out with the bathwater.” I think the dance community has to be careful about devaluing the real creative and responsible work being done by its advocates in the media despite easy antipathies. Some of these voices are new and some have been around for a very long time, but they all have a great deal to add to the discussion.

Share your thoughts on this topic with @thedancecurrent on Twitter or Facebook #dancecriticismnow, or write to us at dc.editor@thedancecurrent.com.

Read the full July/August 2015 issue here.

Tagged: Contemporary, criticism, dance writing, National , Toronto