How do you make a documentary film about the making of a ballet? Better yet, how do you make a ballet film so that a wide television audience will be interested enough to tune in? These questions were definitely keeping me awake in the summer of 2011 after CBC asked me to create a film in celebration of The National Ballet of Canada’s sixtieth anniversary.

At the time, the National had just embarked upon one of its most ambitious projects — the creation of a new production of Romeo & Juliet choreographed by ballet hotshot, Alexei Ratmansky. This new work would replace the much-loved John Cranko version that had been in the company’s repertoire since the Birth of Christ. (I’m exaggerating. The ballet was created in 1964 and Karen Kain, the great company’s great artistic director, rightfully decided it was time for a new one.) My only direction from the CBC was that I had to somehow incorporate the Romeo & Juliet ballet into the scheme of things. Beyond that, I had to start immediately! Ratmansky had already started to choreograph the new ballet and was well into the third week of rehearsals. I took a huge breath, put together a crew and started to film with the National Ballet on August 18th, 2011.

At that time, dance films in Canada were slowly inching their way up the endangered species list as the various outlets that supported them were either dismantled or killed off. Opening Night, CBC’s renowned showcase for the arts, was pink-slipped sometime in 2008 while Bell Media’s takeover of Bravo! in 2011 unceremoniously dumped Bravo!FACT, the internationally acclaimed platform for dance films, onto a distant digital platform. And despite constant harangues by such great supporters as John Doyle, the TV critic for The Globe & Mail, the arts (and dance films) slipped beneath the waves and disappeared from view. As the ship sank, a whole community of directors, writers producers, editors, musicians and performers were set adrift. So, it was an altogether welcome sight from one of those life rafts when the light from the CBC ballet film appeared hovering overhead. Someone from above waved. I waved back. A ladder was dropped and I climbed back on board.

Chelsy Meiss and Brendan Saye of the National Ballet of Canada with steadicam operator, Jason Vieira / Photo by David Hou

In all honesty, I had absolutely no idea what shape the film would take when we started shooting. Would we film some rehearsals prefacing a television presentation of the actual ballet? (Been there. Done that.) Would it be a history of the National Ballet using Romeo & Juliet as a narrative thread? (Yawn.) Or would it be something else? And whatever it was – and here’s what was robbing me of sound sleep – how could I convince a TV audience that a film with ballet at its centre was worth watching? Should I also suggest that chewing cod liver oil would be healthy for them?

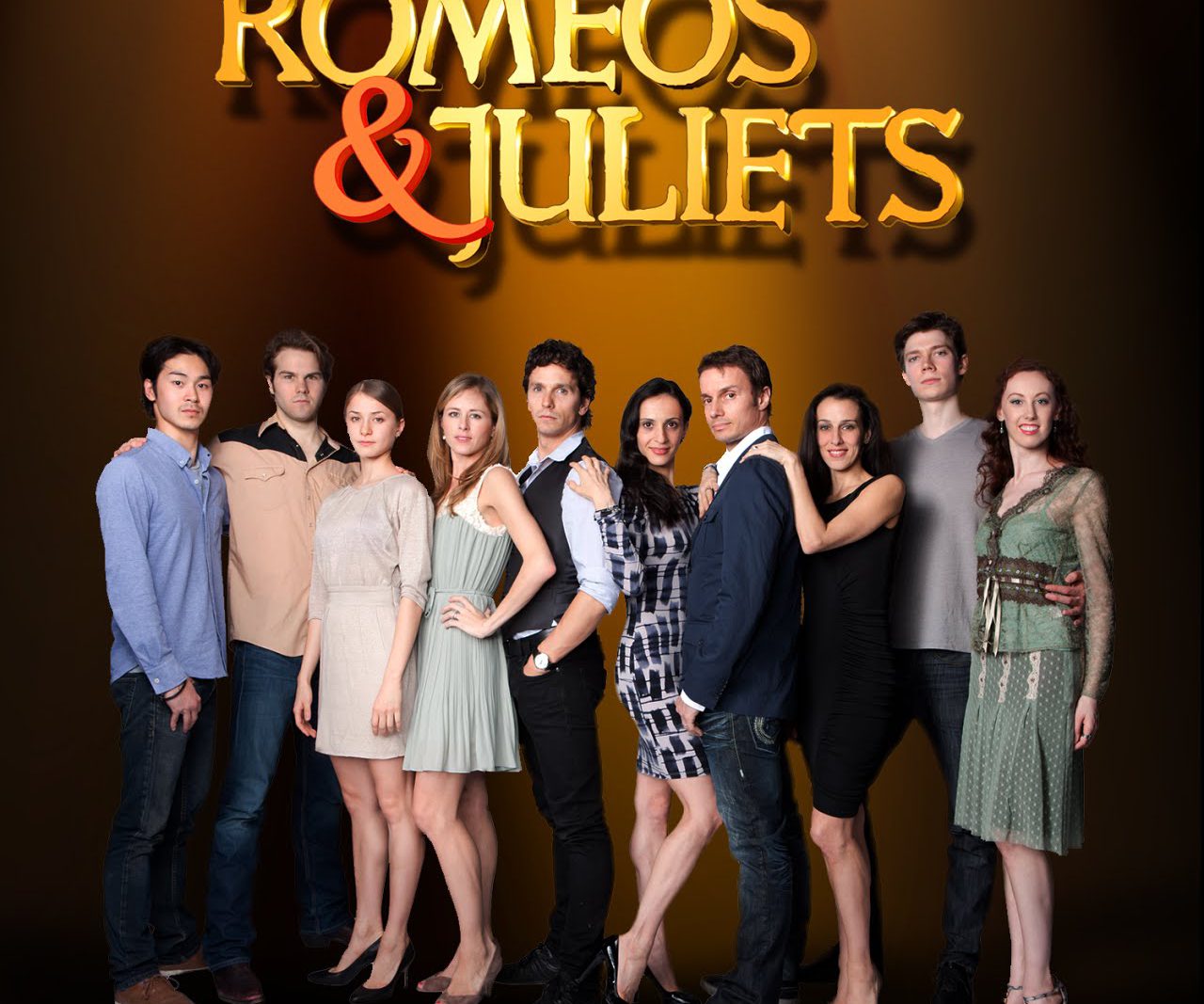

Surprisingly enough, the answer came to me rather quickly and in the most unexpected way: It was right in front of me in plain sight. I noticed that Ratmansky was choreographing with five different sets of Romeos and Juliets. He would be working closely with one couple in the foreground while the other four couples would follow his directions in the background. I turned to a dancer watching from the sidelines and asked why this was so. The dancer explained that Ratmansky needed at least five couples to handle the performances; the choreography was difficult enough that that many couples were needed. This was, in effect, the most efficient way to have all the dancers learn the steps. Beyond that, he hadn’t decided who would be his “first cast”. “What’s the ‘first cast?'” I asked. “It’s the couple who get to perform on opening night. They get their faces on the poster and get reviewed in all the papers”. Sensing that I might not have grasped the importance of this, the dancer went on to say, “It’s like getting the opening night slot at the Cannes Film Festival. It’s a big deal.”

I nodded, staring at the five couples. There it was, the story for the film – five couples rehearsing for a major new ballet, but only one being chosen for the opening night. I knew the approach might have a reality TV feel to it but it quickly occurred to me that the film would also follow the chosen couple right through rehearsals up to opening night, ending with a performance sequence from the ballet itself. It would explore the process of creating art while getting access to the inner sanctums of one of the country’s biggest cultural institutions. “It would be a hybrid,” I said to myself, “something familiar to a TV audience and yet different enough to make it unique.” It would be accessible. It would be engrossing and exciting. It would also be one of the most challenging and emotionally exhaustive experiences of my career. I should’ve taken those cod liver oil pills.

Moze Mossanen with Elena Lobsanova and Guillaume Côté of the National Ballet of Canada / Photo by David Hou

At the end of August, Ratmansky took a break from choreographing the ballet and went off to Europe to honour another professional commitment. In the meantime, I compiled the footage I had shot so far during that month and put together a demo to show CBC the direction I had in mind. Demos, by nature, are strange creatures as they are mostly hyperventilated trailers for a proposed film. While mine asked the question of who would be cast in a major ballet, it was still edited within an inch of its life to make it look as “exciting” as possible. Still, the CBC liked the demo enough to commit to a full production, which would begin once Ratmansky was back in mid October. We would resume shooting the rehearsals and interviews and continue to opening night with an additional two days thereafter to film the performance sequences. The swiftness with which all this had evolved was truly astonishing – six weeks from the time I was first called into the meeting with CBC to the moment we were given the go-ahead for a full production. Usually a project of this size would take about a year or two to set up, a period of time that would include vast amounts of emails, phone calls, meetings and dancing naked around a ceremonial fire in the hopes of bringing forth the forces of good fortune.

Speaking of good fortune, it did indeed show itself when we resumed filming on October 25th, 2011. It presented itself in rehearsals that were intense and dramatic; in interviews where the dancers (including the choreographer himself) opened up about the enormous challenges before them; and in scenes where the dancers faltered under the heavy strain of the workload. I tried to observe and record as much as I could and to ask questions that would uncover for the audience (and for me) the true feelings not readily expressed under the rehearsal studio’s fluorescent lights. But gnawing at the back of my mind was the sense that these same scenes, recorded in all their stark truthfulness, would cause distress, if not outright pain, to some of the featured dancers. What I saw as authenticity or truth, some dancers, in contrast, would see as intrusive, possibly a distortion of the facts. In actuality, my process was completely opposite to theirs: where the dancers worked hard to erase any trace of slip-ups or missteps, I sought to reveal them.

As a filmmaker, I know that the simple act of pointing a camera in any direction can create a point of view or opinion; and editing alone can change the tone or meaning of anything being filmed. And, in fairness to the dancers, I can also readily admit that the film is my point of view of who they are and what they are doing. However, I do keep these in mind at all times during the editing process, particularly in deciding (a) if we should include the scene and (b) how we edit the scene. In each case, I would turn to my editor and ask: “Is this the truth?” If the answer was “yes”, we would keep it. If not, we would discard it.

Nevertheless, as shooting progressed through the weeks leading up to opening night, I found myself in the middle of the maelstrom that comes with premiering a new ballet. Opening night was just a few days away and Ratmansky had not finished the ballet. Imagine a man trying to write a letter in a hurricane and you get the idea of what he was up against. I could see the colour changing in his skin, the creases getting more pronounced in his forehead and the voice getting softer and softer as time kept jabbing him in the gut. But despite the enormous stress and pressure, I never once saw him lose his cool or give a sense that what he was doing was anything less than 100 per cent right. It was an impressive feat to watch.

Elena Lobsanova and Guillaume Côté of the National Ballet of Canada with steadicam operator Jason Vieira / Photo by David Hou

On my side of the camera, other trials were taking place. The cost of filming the performance inside the theatre on opening night was so steep that we had to restage those scenes inside a film studio. We were still allowed to film in the backstage hallways and in the front lobby of the theatre but if the cameras were pointed at the stage or any part of the performance, we would have had to compensate every member of the unionized theatre staff (which numbers about fifty) whether they were active or not. Suffice to say that we might as well have been asked to settle Greece’s national debt with the amount we had available in our budget.

A bigger headache yet was the cost of using the sixty-member orchestra. The fees were so out of our ballpark that we actually began to look elsewhere in order to record a few selections of the Prokofiev music from Romeo & Juliet to underscore the performance sequences. One such place turned out to be Hungary where we discovered we could hire the entire seventy-piece Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra for a fraction of what it would cost to record its counterpart with the National Ballet. I was talking about this rather strange prospect between takes one day when David Briskin, the supremely talented and understanding musical director and principal conductor of the ballet’s orchestra, questioned the manner in which it would be credited on screen: “The National Ballet of Canada … with the Hungarian National Philharmonic Orchestra?” “That would be absurd,” David said. “What’s next: The Canadian Opera Company with The Tehran Philharmonic?”

Within minutes David took aside the orchestra’s manager and set up a meeting with the musicians’ union in order to come up with a solution. I was not party to the negotiations but a deal was struck so that we could stay in Canada and record the ballet orchestra for the documentary’s performance sequences. It was a huge relief, of course, as all the tempos and musical arrangements the dancers would be dancing to would be preserved for the playback. The performance sequences themselves were filmed over two days at the end of the production schedule. Thereafter, we settled in for a five-month editing period. Given the intensity of the shoot and the myriad of challenges we faced on a daily basis it was a good feeling to settle into a darkened room with only one other person – my editor, Robert Swartz.

And yet the editing phase is another test of one’s mettle. Whereas in the past I had been very lucky to exercise a great deal of creative freedom in making my films, I was now dealing with a network that had a hierarchy as complex as a ballet company. There were many more notes than I was used to – more suggestions, more phone calls and emails – and, heaven help me, more teasers and bumpers. Even more problematic was the ever-decreasing running time of the actual film. Back in the early part of this century, you could deliver a forty-eight-minute film to run in a one-hour time slot. Today, the running time of a one-hour program is forty-five minutes, less one-minute for credits and another minute for teasers and bumpers, leaving only forty-three minutes for the actual content. Fortunately, I was working with a great group of execs at CBC who provided a number of strong, creative suggestions throughout the editing of the film.

Romeos & Juliets got a splashy premiere on the evening of May 22nd, 2012 before a packed audience at the Isabel Bader Theatre in Toronto. Even though all of the dancers showed up for the photo op and hors d’oeuvres in advance of the screening, one of the stars left before the lights went down as she was “too embarrassed” to watch herself. Some things take time, I know, but I’m hoping that she’ll come to see how much the audience embraced and loved her for the flaws that she was too reticent to witness.

As for the reviews, they went from grudging to good. My sense was that the film played remarkably well for audiences who wouldn’t ordinarily reach for a ballet film. But as for future dance films, it’s hard to say. The pendulum seems to have swung more in favour of reality-based TV shows like Dancing with the Stars, Breaking Pointe and Dance Moms with broadcasters less inclined to support original, director-driven or choreographed-for-the-camera stories or ideas. The latter is what set Canadian filmmakers apart from their European or international counterparts whose work concentrates on either arts documentary subjects or TV presentations of works filmed off the stage. But everything, I’ve come to realize, is cyclical – it goes up and it comes down. We’re in that down period again right now, particularly as they’ve killed off dance films in the Bravo!FACT program, one of the prime venues for the kind of unique, dynamic and visionary work our country is known for. But I remain optimistic for a couple of good reasons. Audiences love to watch dancers and great choreography and as long as those two things are alive, we can keep the hope of dance films alive. And I’ll be there at the front of the line to watch. I may even take a bit of cod liver oil to keep up my energy.

Watch Romeos & Juliets in its entirety along with behind the scenes footage at cbc.ca.