In 2014, Michael Trent, artistic director of Dancemakers at the time, had a big task ahead of himself: a full weekend of digging through the company’s 40 years worth of files and records. Instead of going it alone, he turned the work into a celebration of sorts by inviting former company members to participate. Dancers from all eras sprawled across the studio, wading through stacks of newspaper clippings, programs, posters and pictures, trading stories and memories, as they organized the material that would preserve the story of Dancemakers. They carefully renamed materials, removed staples and moved them into acid-free folders to be considered and curated by Dance Collection Danse, Canada’s dance archive.

Three years later, the costumes had to be dealt with. Amelia Ehrhardt, Dancemakers’ most recent curator, was cleaning out the company’s storage room. It was stuffed with costumes, some that had been with the company for more than 40 years. After sorting through the decades of accumulation — Ehrhardt too would spend the entire weekend in the studio — the clutter was tamed. Once again, former company members returned home to Dancemakers’ Distillery District studios to pick through old costumes, set pieces and other memorabilia. Among them was Carol Anderson, an original founding member. She flipped through clothing tags, recalling which dancers had worn the costumes, while describing the performances. At one point Ehrhardt examined a pair of shoes and saw a dancer’s name scrawled in the sole: Susie. And another pair: Julia.

“I don’t know why I feel so emotional right now,” Ehrhardt told Anderson. “This isn’t my history. I wasn’t here for these things.” But Anderson said of course this was Ehrhardt’s history. “You’re the curator of this space now,” Ehrhardt remembers Anderson saying. “These are your teachers. These are your mentors.” Anderson is one of these mentors: in 2010 Ehrhardt performed Polyhymnia Muses in MOonhORsE Dance Theatre’s Older & Reckless presented at Dancemakers, a solo that Anderson created in 1988.

***

For 46 years, Dancemakers has been a foundational institution for contemporary dance in Toronto. In its current form, the company hosts multi-year artist residences, alongside presentations and other programming that supports artistic development. For decades previous, it functioned as one of the city’s most innovative performance-based dance companies.

Dancemakers and its history are, of course, important not only to its artistic leaders and collaborators but also to its wider dance community. This is true now more than ever, as the organization is in the midst of another critical self-assessment: to consider its past and future. In November 2020, the organization’s board of directors announced the company’s permanent closure effective July 31st, 2021, after a final season of programming.

Dancemakers is one of the oldest dance organizations in Toronto, and the losses associated with its closure are multiple. It marks the loss of rehearsal and performance spaces, the loss of a dedicated hub for creation and research and the loss of hard-won organizational structures and financial resources that provide security and growth opportunities for Canada’s dance artists. It would ultimately be the loss of an institutional voice that shaped dance in the city. Importantly, the closure has raised questions about the protection and stewardship of valued institutions that sustain dance artists in the country. These losses are so great that they inspired collective action from many unwilling to accept them as inevitable.

***

Since the beginning, Dancemakers has always sought to explore the possibilities of dance, which is part of the reason why the announcement of its closure was so painful. Not just for the loss of an institution – a home for countless dance artists – but for an organization that has always prioritized creative inquiry, even if its methods for accomplishing this evolved over the years. “I have a theory that things go on as they begin, that there’s an energy or a shape around things creatively as they begin,” says Anderson. “In that first curious creativity, there really was a seed of something that has sustained throughout the life of the company.”

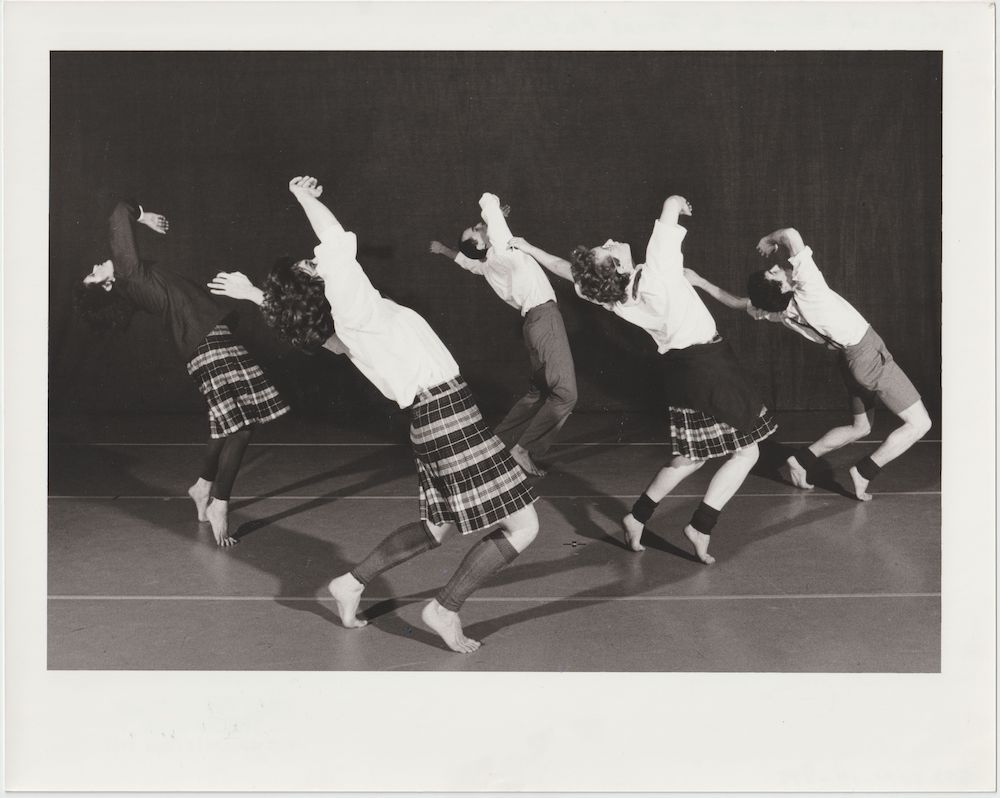

Dancemakers, established in April 1974, was originally the concept of Marcy Radler and Andraya Ciel Smith, two graduates of York University’s then fresh dance program. They were soon joined by additional members (many from York) including Anderson, Peggy Baker, Patricia Fraser and Patricia Miner. “We came out of York with the idea that we were dancers and we could do whatever we wanted to,” Anderson says. They were inspired by the program founder Grant Strate’s idea of the “thinking dancer,” described as “a dance artist who had many dimensions,” Anderson explains. Intended to be a summer project, Dancemakers was encouraged to continue after an eclectic and well-received performance in the fall of that year.

The idea of a collective was integral to those early days, and the group decided together what repertory they wanted to keep and commission. In the ’70s, it was common for Canadian dance artists to train abroad, and the group’s members had returned with new ideas that informed their shared work. Dancemakers was built on a collective ideology that helped differentiate them from the only established dance companies in Toronto at the time: The National Ballet of Canada and Toronto Dance Theatre. “We didn’t look like Toronto Dance Theatre dancers,” says Anderson, comparing Dancemakers with the Graham-focused troupe. Although many of the company members had Graham technique training, it wasn’t their focus at Dancemakers. “We developed our own style that was based on the Limón style. … Our barre class was pretty unique,” says Anderson. The collective also expanded the idea of what dancers could do and be interested in. “So there was more of an equality, not so much the hierarchical, you know, choreographer as the queen bee, and the dancers as sort of the executors of things.”

Over time, consideration of structure (including governance, touring and promotion) became necessary for the company to keep operating. In order to get funding, Dancemakers’ organizational model had to look more like a ballet company, which was viewed as the standard for all dance companies at the time: “The model smiled upon by councils who had the money,” explains Anderson.

Dancemakers was a co-operative for its first three years, and by 1977, Baker and Miner were named co-directors. Anna Blewchamp did a brief stint in 1979, followed again by Baker. From 1980 to 1985, Fraser and Anderson were co-artistic directors, after which Anderson continued on her own until 1988. The company would go on to present pieces by Karen Jamieson, Paula Ravitz, Judith Marcuse, Jennifer Mascall, Lar Lubovitch and Paul Taylor, among many others. “People wanted to be making dance and people wanted to see the company too,” Anderson says. “It was very well regarded. The dancers were feisty and great.” As Julia Sasso, a longtime company member, puts it, “There was never a bad dancer in Dancemakers.”

In 1983, Sasso went to the newly opened Premiere Dance Theatre (now the Fleck Dance Theatre) on Toronto’s waterfront. The former warehouse had been redeveloped with culture and recreation in mind, and Dancemakers was performing. “I’m not sure why I went to see this company, Dancemakers,” Sasso says, “but I did.”

There was never a bad dancer in Dancemakers.

–Julia Sasso

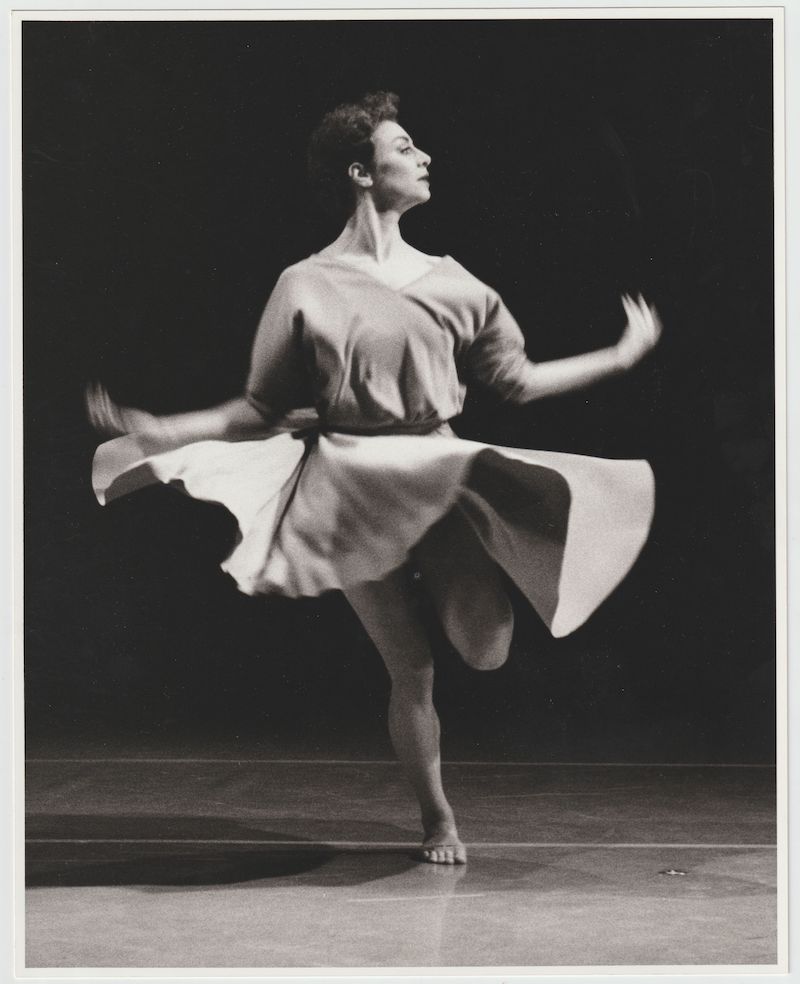

Sasso, who had trained to become a ballerina, was not dancing at the time. But Dancemakers would change that. “I was completely blown away by the dancing, the choreography, the dancers,” she says. “It wasn’t what I imagined modern dance to be. I had a very limited view of what modern dance was.” She also saw herself in the work. “I thought, ‘Gee, I can dance like that. That’s the kind of dancing I love to do.’ ”

Stirred by this recognition, Sasso sought out Dancemakers’ open company classes almost immediately. Compared to her upright classical background, through Dancemakers she was “discovering a new kind of freedom in moving that had a lot more breadth and depth” than she had been used to, she says. After auditioning with 60 other people competing for two spots, she was hired and worked with Dancemakers for 16 years, including 12 as the company’s assistant artistic director and principal company teacher.

***

When Anderson stepped down in 1988, she was the only original company member left and sensed Dancemakers needed a change to thrive. She describes the dance landscape as undergoing a “huge shift.” The board of directors then appointed choreographer and dancer Bill James as artistic director, who had just staged two inventive and lauded works in Toronto.

James’s appointment resulted in a significant aesthetic repositioning for Dancemakers. While the company had always been innovative, it still resembled a typical repertory company of the time. James’s artistic practice included site-specific work and transforming unconventional spaces. In 1987 (before joining the company) he created a piece that took place on the top floor of a GE light bulb manufacturing plant in Toronto’s west end. “It was a beautiful, huge space with a big shed roof and glass all the way around all sides,” he describes. “And these big doors that opened up into the sky.” The dancers and the audience moved through the sprawling industrial space, which James says was the size of a football field. He brought his inventive style to Dancemakers.

“When a company makes a big shift like that it doesn’t suit everybody,” says Sasso, who became assistant artistic director under James. He struggled to receive full board support for his vision and ultimately, after two years, left Dancemakers. “I was a little bit dismayed by the way things ended,” James explains. “The board of directors, I felt, were overstepping their role by dictating artistic direction.” In the end, he says, “It wasn’t a good fit.”

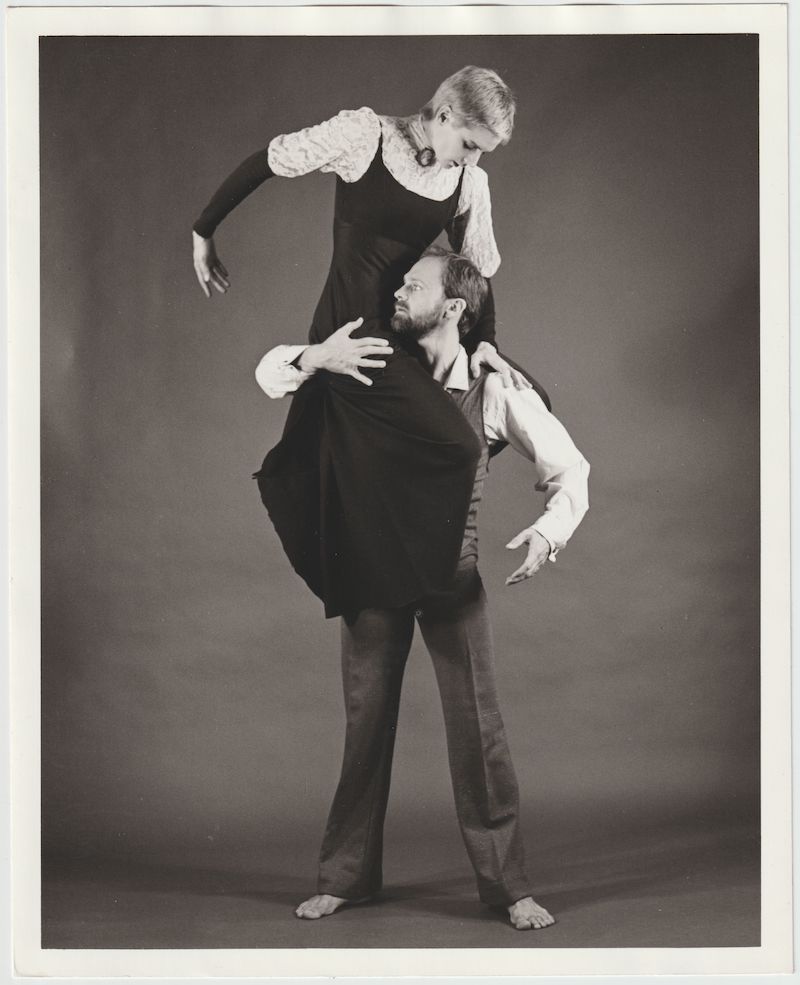

With James’s successor, the company became an even stronger instrument of a sole artistic voice. Serge Bennathan brought his bold, physical dance style to the company, intending to push it further and develop a body of work. His impression was that the Toronto dance scene was heavily influenced by American modern dance. “My work was very different and totally out of this mode,” Bennathan says. “I wanted to go further with this to try to create a space … where people could experience dance at a different level.” His goal was transcendence: choreographically, emotionally and how the audience related to the work. “I think that people were not looking at dancers onstage. I think people were looking at humans going through something that they could relate to.”

It was a successful formula. In the 16 years Bennathan was artistic director, 12 works he created for Dancemakers received Dora Mavor Moore Award nominations. Sable/Sand and The Satie Project were awarded Outstanding New Choreography in 1995 and 2003, respectively. The company achieved new notoriety as its identity was shaped around Bennathan. And beyond his work, one of Bennathan’s most consequential contributions was to bring Dancemakers to its current home.

I think that people were not looking at dancers onstage. I think people were looking at humans going through something that they could relate to.

–Serge Bennathan

The story of Dancemakers is not just one of people but also of its various homes across Toronto. In the company’s early years, they danced wherever they could, including Toronto Dance Theatre’s studios at night, after everyone had gone home, and if York University’s studios were empty, Strate would let them use that space. They also performed at St. Paul’s United Church on Avenue Road, which had less than ideal conditions for their first performance: there were no wings, just boards acting as ramps, running onto the stage.

The company then settled in the Bathurst Street United Church, in the former lounge (which came complete with a fireplace). Eventually, the church made renovations and Dancemakers moved into the basement. It was spacious compared to the lounge, though being in the basement, “It had that garden flat, slightly dim light,” Anderson recalls. “But it did have light!” It also came with change rooms and much-needed office space for the growing company.

Dancemakers’ next home of 15 years was at 927 Dupont St., an enormous second-floor space where the company built a sprung floor. The studio could accommodate 50 or so audience members and had high ceilings and big windows. Though spacious, the single room made simultaneous rehearsals difficult. The studio was also above a car mechanic and lacked proper ventilation. Hot days could be excruciating: fumes rising from the garage paired with Bennathan’s physical and demanding choreography. “So suddenly at 3 o’clock it’s ‘OK, let’s stop; we can’t breathe anymore,’ ” Bennathan says, laughing. “It didn’t happen every day, but it happened.”

Feeling full of possibility in the new millennium, Bennathan and Andrea Vagianos, administrative director at the time, were eager to find a better-suited space. During the search, an opportunity presented in Artscape, which was developing affordable space for artists and arts organizations in the Distillery District. Dancemakers applied for two studio spaces – one that would double as a performance venue – plus office space.

Under the agreement, Dancemakers would be a subtenant of Artscape. “We agreed to a fixed annual rent increase, but there was a clause that we fought unsuccessfully to get removed, allowing for ‘additional rent’ to be charged in extraordinary circumstances to recoup unexpected losses,” Vagianos says in an email. “I was assured this would only be applied in extraordinary circumstances. However, it was applied each year I worked there.” Despite these and other unexpected accommodations (including soundproofing the floor because the studio would be above a fine dining restaurant), “The promise of being part of a community of artists downtown and under one roof seemed greater than the compromises,” Vagianos explains. Dancemakers moved to the Distillery in 2003. “It was a beautiful boost for the company,” Bennathan says, looking back. After paying their dues, Dancemakers secured a professional space. It felt like a company maturation. “There was this sense of being in a home,” says Bennathan.

***

With the move to Artscape came an additional studio, and the company officially established itself as Dancemakers Centre for Creation.

Creation had always been important to the company. Choreographic workshops had been offered since Dancemakers was at the Bathurst Street United Church, and under Bennathan these workshops became structured as choreographic “labs.” Sasso attended one of these labs – “a baptism of fire,” she says – and was challenged by mentor Murray Darroch to improvise every day and create quickly, never dwelling too long. What eventually emerged was her first full-length work, Sporting Life, presented by DanceWorks in 1996 and again in 2016, for the work’s 20th anniversary. The work was nominated for two Dora Mavor Moore Awards in 1997: Outstanding New Choreography and Outstanding Performance by Mark Shaub. “That was pivotal in both my development as a choreographer but also in my beginning to learn how to be a mentor and choreographic facilitator myself,” Sasso says. “I’m an example of the type of artist that has simply learned everything I know from experience, from doing. My education has been 100 per cent experiential.” These choreographic opportunities were something that made Dancemakers an attractive place for artists to learn.

Now, with the Centre for Creation, choreographic labs and residencies became a focal point embodied in a physical space, and not just for Dancemakers artists. A presentation could happen in one studio while rehearsals or workshops took place in the other. “It doubled the possibilities,” Bennathan says. “That was the thing; it was to create. I think at the end, when I created the Centre for Creation, it was part of the same philosophy. It was even more to create the space where there will be a different vision of dance.”

***

In 2006, Bennathan instinctively felt that his cycle with Dancemakers had come to an end. Proud of what had been accomplished, he was looking to simply be an artist again, free from having to plan for an entire company. Trent was also looking for the next phase of his dance career. He was well acquainted with the company, having first been introduced when taking Dancemakers’ classes at the Bathurst Street United Church in the ’80s. Trent recognized the unique opportunity and privilege leading the company would be.

Under Bennathan’s direction, the company had mostly become synonymous with his work. “If you were going to see a Dancemakers show, you were going to see a work by Serge Bennathan,” Trent says. “I was very clear when I took the leadership role that I wanted to work collaboratively with other folks and other voices.” For Trent, this approach “also reflected back to some of the early ethos of the company, which was a collective.”

Trent operated Dancemakers under these principles during his eight years as artistic director. “He was into this idea, the truest idea of collaboration,” says Robert Abubo, a company dancer at the time. “There were a lot of conversations and questioning about how we ran ourselves or organized ourselves.” The company was now established in Artscape and had wonderful artistic neighbours and a well-equipped venue that allowed for other initiatives, such as supporting youth and emerging dance artists. Trent also continued dance curation and presentation through Dancemakers Presents, an initiative Bennathan had started.

Over time, it became clear to Trent that high occupancy costs were limiting Dancemakers’ ability to create work and connect with audiences. Artscape itself is a tenant – it does not own Artscape Distillery Studios – and passed on rent increases to its subtenants. According to Trent, this meant that Dancemakers could expect a roughly 3.5 per cent increase every year. In the media release announcing Dancemakers’ closure, Louis-Michel Taillefer, former board chair, explained that 36 per cent of Dancemakers’ 2019-20 operating revenue went to occupancy costs. The company had seen an “annual increase as high as nine per cent in the last four years.”

“Those increases became untenable in an accumulative fashion,” Trent says. Dancemakers’ organizational equation – the deficit between a company’s ambitions and its resources – was becoming too wide. In consultation with dance artists, the board and administrative leadership, Trent attempted to rebalance it through one of the most radical changes in Dancemakers’ history: shifting to the Incubation Production House model.

Under this model, the role of artistic director became one of curation – supporting artists-in-residence. These residencies would be “more than just two weeks of a lab; this is going to be your home for three years,” Trent says. “What do you need and how can we support and foster that relationship with your artmaking and the public?” While significantly different, the new model still carried the values that had always guided Dancemakers.

However, Trent did not get to participate in its realization. He created a two-year transition plan where he would shift to the role of resident artist before departing the company after a complete 10 years. But “The board decided that once the idea was in place … they wanted to bypass the transition,” he says. Trent’s contract ended before the new model was introduced, a disappointing surprise.

***

Trent’s departure in 2014 marked not only the beginning of another period of change for Dancemakers but also instability. To enact Trent’s plan, Benjamin Kamino, a company dancer, stepped into the role of co-curator alongside Emi Forster. They left after just a year, and Ehrhardt picked up the curatorial reins in 2015 until 2019.

Ehrhardt was interested in the resident artists already at Dancemakers and was drawn to the company’s history and potential. “At the time,” they say, “[Dancemakers was] the only centre or organization in Toronto on operating funding that was really primarily dedicated to more experimental, conceptual modalities of dancemaking.” Also appealing was the organization’s collective roots.

It was a difficult transition: there were no other full-time staff at Dancemakers when Ehrhardt joined. But they quickly adapted. In addition to working with the company’s resident artists, they folded Flowchart, their own multidisciplinary performance series, into Dancemakers; they facilitated workshops on writing artist statements; they taught popular adult beginner contemporary classes; and they introduced the Peer Learning Network, an initiative for emerging choreographers who were provided free studio time and collaborative meeting opportunities. “Something that I was really dedicated to as the curator,” Ehrhardt says, “was finding ways to support artists throughout the progress of their career.”

The atmosphere of support is something that still resonates for Dana Michel, one of Dancemakers’ first resident artists under the new model. Arriving at the charmingly bricked Distillery District, with its restored heritage buildings, felt like the lap of luxury because of not only the surroundings but also the generosity of her collaborators and the rarity of what was being offered to her by the company: “Please explore your practice, and we will pay for you to come here,” as Michel puts it.

Walking through Dancemakers’ halls, Michel would often question the good fortune of such freedom, expecting to be fired, or to be held accountable to a certain type of productivity. “You said that I can experiment, so I’m going to experiment. That doesn’t always look super practical,” she says. But the organization’s offer was genuine. “They just stuck by me. Having people and organizations stick by you, that is art gold. That’s what lets you do the shit that you’re supposed to be doing. My time at Dancemakers was just straight-up art gold.”

In November 2019, Ehrhardt left Dancemakers to focus on their own artistic practice. They were the third artistic leader to exit the company within five years – and Dancemakers would be without any until the appointment of Natasha Powell, announced as the artistic producer in November 2020, alongside news of the company’s closure.

***

By taking on the job, Powell stepped into the difficult role of ushering a company to its end. She was going to support the current resident artists (curated by Ehrhardt) as they adapted their projects during the pandemic, while also providing space to consider the dance community’s needs and address inequity in the sector. “COVID-19 and the closure of Dancemakers has finally forced the dance community to pause and take notice of the imbalances and racial injustice that plague our society and seep into our sector,” Powell says in a December 2020 blog post on the company’s website.

While the pandemic contributed to the company’s decision to close, it did not initiate it. “The board started to seriously consider closing the organization as one of a multitude of options about two years ago,” Taillefer says in a November 2020 email. “The main concern was indeed the rising costs of operations, combined with a gradual but substantial decrease of support from both funders and audiences. … Toronto’s massive economic growth and success is making artwork spaces become increasingly unaffordable.” Some are disappointed such a drastic decision was made without warning and without community input. “If this question was put before us,” Abubo says, “I think we would come up with a creative solution to keep it alive.”

It turns out he isn’t alone in the feeling. In the late fall of 2020, a group of concerned colleagues, all with artistic ties to Dancemakers, assembled and co-authored a “request for pause,” seeking to halt action towards closure, relieve the board of directors and create a forum to discuss possible futures for the organization. The “request for pause” working group was motivated by a perceived lack of transparency and consultation around the decision, which in their eyes failed to properly acknowledge the huge impact and loss for the dance community. “This group of individuals,” referring to Dancemakers’ board of directors, “specifically chose to close Dancemakers, and the pause is seeking for possible outcomes that do not include closure,” states the Request for Pause Working Group in an email to The Dance Current. More than 300 names were attached as signatories when the letter was delivered to the board of directors on Dec. 16th, 2020.

Michel was one of them. “I didn’t put too much thought into it,” she says, of signing. “Look at what [Dancemakers] did for me.” Speaking about resources for dance, she continues: “We’ve got to protect what little things we have. And Dancemakers is not a little thing. It’s a big thing that has been built up for a long time and has supported many people.”

Brodie Stevenson also added his name and reached out to the working group to offer additional support. That became useful when Dancemakers’ board of directors publicly responded to the letter, agreeing to step down if a minimum of four new board members were nominated and approved. It was a time of urgent action: the board replied on Jan. 6th, and applications needed to be submitted by Jan. 15th. According to Stevenson, the board would only communicate with interested parties who put themselves forward as potential new board members, and so Stevenson stepped forward as a nominee.

We’ve got to protect what little things we have. And Dancemakers is not a little thing. It’s a big thing that has been built up for a long time and has supported many people.

–Dana Michel

At Dancemakers’ annual general meeting, on Feb. 1st, Stevenson and four others – Robert Abubo, Kate Hilliard, Sebastian Mena and Simon Rossiter – were elected to replace the existing board. The decision was immediate. Just days after the meeting, Stevenson described the challenge of having no formal transitional supports, only having a snapshot of the company’s financial state, and not knowing what had been communicated to employees and artists. “We stepped in on Monday night into a lot of fact-finding,” Stevenson says.

On Feb. 23rd, the new board of directors released a public statement. The statement listed the board’s most urgent priorities including supporting the artists-in-residence, along with Powell. However, they also announced that Powell has resigned as artistic producer, explaining that she has “made the decision to step away from Dancemakers, as the original job for which she was hired has changed completely.” The company also won’t be staying in the Distillery District past July.

The board’s other priorities include starting an inclusive community consultation process and securing funding during this time of transition. “All we can do in the short term … is to try and articulate a hope and a blueprint for that hope that Dancemakers can change and grow into something that is needed and necessary,” says Stevenson, who is now the president of the new board. “While we don’t have to know what that final structure might look like, we have to come up with a convincing argument for the hope.”

Tagged: Contemporary, ON