Fashioned not unlike a television reality show, “Débranché”, PPS Danse’s new production, evokes the highly disposable but hugely popular genre that drives commercial television worldwide. As is the case with Mark Burnett, the producer and creator of the CBS program “Survivor”, choreographer and PPS Artistic Director Pierre-Paul Savoie knows how to sell his wares. Here he’s put aside his high-tech affinities of the past (“Pôles”, “Strata”), and invested his energy in a more straight-ahead unplugged dance-theatre piece, which enables the work to be toured widely without much technical baggage. (English and Spanish versions are apparently ready to go.)

The show at the Gésu (an intimate stage, with not much depth, often used during Montréal’s summertime jazz festival for its piano series) opens casually with a dancer on stage stretching. Another arrives, water bottle in hand, and massages his foot. A technician makes last-minute adjustments. A voice is heard overhead: “Breathe in and out,” it says. “Leave your day behind; leave your worries behind.” From the get-go, we’re well aware as audience members that we’ve been invited into a behind-the-scenes look at dance, and we sense the receptive state of the dancers.

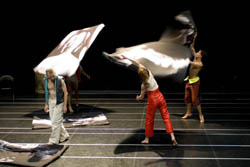

The evening is divided into three short works: “Solosansfil”, “Extase” and “Louves”, a solo, a duet and a trio in that order. The young cast (Mathieu Campeau, Kim Girouard, Carolyne Méthot, Amélie Nappert, Karine Cloutier, all recent graduates of l’Université du Québec à Montréal, les Ateliers de danse moderne de Montréal or l’École de Danse de Québec) and veteran performer Normand Vincent (splendid as the dopey good-guy tech) work together the best they can, but the script by Michoue Sylvain is underwritten and insipid. The subtext of the piece — the dance world turning on itself — expresses the notion that there is something devouring about the art of dance. Amid revelations about the day-to-day realities in the dance world, a theme of dominance and submission plays out. Just how much will the dancers take at the hands of the tyrant director (referred to as Paul-Pierre, a man who prefers to tell the world to kiss off)?

The opening solo features a feisty Cloutier showing an effective display of tension in her body, and a frenzied quality in the “egg-beater” arm movement and quick spins that ensue. Structurally, the entire evening is set up in this section: we learn of the nagging choreographer (heard in a voice-over at the start of the show) his incompetence and the general malaise of the Dancer, who communicates with him over a cell-phone (hence the “sans fil”, “wireless”, of the title), not to mention brief conversations with her mother, her ex, and a potential part-time employer at the local pharmacy. We learn the Dancer is poorly paid, the working conditions are dismal, and what a misery this dancing life is (“I’ve chosen a career where I’m silent,” says Cloutier derisively) — but yes, it is a chosen profession. The protagonists, in this and the other pieces, are in an insecure world.

The dancing in the opening solo, as well as in the subsequent potentially sensuous pas de deux (Campeau and Méthot) and the final trio by Girouard, Nappert and Méthot — a unison tandem of passé développé extensions passé attitude postures and spins — are constantly interrupted by the verbal gags and the constant petty banter. Thus, curiously, Débranché is not really about dancing at all but is more a theatrical piece focussing on the day-to-day commonplace, yet intense and anguished lives of the Dancers.

We see the Dancers “in process”, doing their dance, talking back to the Choreographer (who issues edicts over the sound system in the theatre) and, near the end of the piece, with said Choreographer berating the Dancers in real-time. This framed “backstage dance” ultimately questions what happens in the making of dances for the stage. It’s unclear why Savoie (who has worked steadily for the last twenty years as a choreographer, somewhat less time as a dancer, and for the last few years also as president of Quebec’s Regroupement québécois de la danse) and his scriptwriter want the audience to become complicit in the ensuing humiliation of the Dancer. There isn’t much to envy or admire in any of these Dancers; all are portrayed as confused, obsessed and narcissistic conscience-free types (who will rag on at length about the dreaded Choreographer, at any opportunity). The whole enterprise seems rife with unhappy and willful misfits.

As unsubtle as the script is (at one point an exasperated dancer shouts, “What am I doing here? I’m wasting my time”), the choreography itself is even less sophisticated. The movement vocabulary is limited to something akin to a choreographed workout — spiral the torso while reaching up and back, or reach the left arm as you lift higher out of the pelvis — and is elementary in terms of spacing. However, the relentless nature of the movement does effectively underline the thematic stripping away of layers and layers of artifice.

The worst thing about “Debranché” is its self-reflectivity. Any attempt at irony is beyond the scope of the work here, and any perceived hint of comic vivisection fails miserably. To use the Alice metaphor, this is one Looking Glass world we don’t want to stray near. The material in “Débranché” is calculated, formulaic stuff. The only audacious thing about the piece is that Savoie has pulled the plug on his technological pre-occupations of the past. Nevertheless, with the right salesmanship, à la “Survivor”, and a proper re-writing and re-directing, this serpent-swallowing-itself piece, with its energetic cast, could potentially have audiences grinning from ear to ear.

Tagged: Dance Theatre, Performance, Montréal , QC