This mixed program featured three choreographies, each one exploring the relationship between movement and language, and the interplay between the sonic and the visual.

I had the pleasure of seeing a precursor to /vər’bādəm/ by Catherine Murray while Murray was completing her MFA at York University. Her project, which started as an inquiry into the lives of young mothers, has developed to produce much broader questions about an artist’s responsibility toward another’s words.

In the first segment, performers Andrea Spaziani, Denise Solleza and Christy Stoeten danced phrases, often directed to each other, in a manner that felt conversational. There was a play-like atmosphere as the dancers exchanged movement, clearly picking up and developing threads from one another while moving through silence.

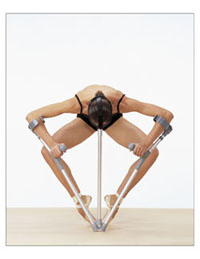

They danced expansively, lunging to explore different levels and swooping their limbs in round, circular motions. All the while, a set of chairs, one for each dancer, waits in a line behind them, where the dancers later sit impatiently, shifting while briefly examining the audience before beginning to move again. A fourth chair held a white plaster casting of a pregnant belly, which the dancers don’t acknowledge.

Following this section, and rising abruptly from their chairs, the dancers form a line. They walk forward performing articulate gestures with the upper body, each gesture accompanying a spoken syllable. The connection between speech and gesture was highly organic with the crisp enunciation amplifying the quotidian movements, and vice versa. The vocal work was excellently delivered and resonated well in the narrow, brick-walled space.

In another abrupt transition, the dancers drop the previous task to move upstage toward the chair holding the casting. They lie on the ground, grasping the chair’s legs while an extended interview recording plays.

The recording was one of the interviews Murray conducted with young mothers in collaboration with Jessie’s — The June Callwood Centre for Young Women. As much as I felt moved by this disembodied voice, being jarred away from such a captivating formal exploration of movement and sound made this sudden shift toward emotionally laden language overwhelming, and I felt as though I had jumped into an entirely different performance.

When the dancers become mobile again, another voiceover plays. This time it is the choreographer’s own voice, describing a workshop in which one of the performers was a young mother herself. The participant, we were told, questioned the easy ability of the others to dance along to these voices when she had found herself completely arrested by them.

What first felt like a forced juxtaposition of ill-matched choreographic fragments reveals itself as a dramaturgical strategy. When the dancers finally start to embody the words from the first audio track of the young mother’s voice, they are not dancing to or with them; instead, one of the dancers scatters slips of paper with lines of dialogue from the mother’s story onto the floor. The others take turns randomly selecting one and reading it aloud while another transliterates each syllable of sound into the gestural language to which we were introduced at the beginning of the piece. Emotionally laden quotations like, “Why did you have to become like all the rest?” are transformed into silent movement phrases articulating “…lī – k – ɒ – L…” The incredible focus in order to achieve such a task, and more importantly, a heightened responsibility to each word, emerges.

/vər’bādəm/ concludes with the dancers moving faster and faster between the tasks of reading and translating. As the speed increases, so do the difficulty of their tasks, but the dancers become comfortable in their physical translations as words are repeated. They continue dancing and begin to separate the movement from the words, yet dialogue lingers in my mind. There was never a shred of pretense in the dancers’ use of their verbatim score.

The strategies employed to distance the experiences of young mothers from those of the performers did not force the words and dance into isolation but brought them closer.

In Until Tender-Crisp III, Christy Stoeten similarly makes use of voiceovers, but of a more irreverent variety. Music ranging from high-energy dance tracks to soulful ballads were interspersed with anecdotes featuring such characters as the high school dance partner who reeks of Cool Ranch Doritos or the church-going neighbourhood friend who isn’t clear whether it’s the body that goes to heaven and the soul that stays on earth, or vice versa. The latter story ends with Stoeten (or what I presumed to be her voice) admitting she thought the soul was an organ and frequently imagined “rows and rows of caskets with a single pulsing organ inside.”

Such evocative images and songs, inseparable from the memories they drudge up, are weaved throughout the piece alongside a movement score that is notably more constant. Refrains of running from one edge of the space to another with quick directional changes, and laterally moving sequences of small, angular articulations in the upper body recur throughout the piece.

The cue for a change in audio throughout is Stoeten balancing on one leg, arms raised with her other leg extended at ninety degrees. As she drops into a dramatic lunge, the audience is jettisoned into another musical genre or a period of silence. In each of these changes, I was acutely aware of what lingered. The richness of Stoeten’s connection to sound was always palpable. On one occasion, I noticed the preceding song continuing to play in my head, adjusted to the rhythm of Stoeten’s now silent dance.

Each song had a cheekiness about it (many audience members chuckled at the start of Darude’s Sandstorm) and Stoeten allowed herself to be affected both rhythmically and emotionally. Her dancing fully embraced each song without a hint of ironic nostalgia, yet the entire performance was suffused with lighthearted humour.

For all of its seemingly disconnected elements — at one point Stoeten retires to the back wall, opens up a pail of orange wedges and casually snacks for a couple of minutes — it was fascinating to watch her going about her business, and her choreography, in the midst of such drastic changes to the soundscape.

The relationship between sound and movement in Between Tender Crisp III made for an incredibly compelling work as it highlighted the possibility for bodies to act on sound. Stoeten allowed herself to be affected by the music not by passively taking up its rhythms but by filling in the spaces within the sound. Whether she was darting through space to Standstorm or slow dancing with herself in the centre of the stage to a disco-era ballad, her musicality highlighted the gaps in the rhythms and choruses with which we thought we were so familiar.

In preparation for Rafters choreographed by Andrea Spaziani, the lights turned a golden yellow and chairs were redistributed so that the some of the audience partly encircled the trio of dancers — Alicia Grant, Julia Male and Spaziani — wearing loudly shimmering gold pants. Between the warmth of the lighting, the sheer number of bodies onstage and a constant breathy drone in the soundscape, there was a sumptuousness to the work that I enjoyed dwelling in.

The recorded score seemed to be composed of Spaziani speaking while moving. In one particularly pleasing moment we hear her musings (read: complaints) about struggling to do pull-ups while the dancers simultaneously struggle to pull themselves off the floor. There was a rich synchronicity between the palpable tension of the voice and the bodies; however, my experience of the sound and movement acting on each other began to deteriorate as the dancers made their way off the floor. They expertly filled the space, moving along walls, between banks of audience members and into the extremes of upstage and downstage. The desire to explore and activate space appeared a much stronger motivator to the languid movement.

The movement was internally focused and often composed of purposely truncated articulations — limbs dabbing the surrounding space, but remaining close to the body, and traversals of space in small steps while shifting and contorting the upper body playfully. The performers seamlessly melded into this particular movement aesthetic, which appeared improvisational. Each dancer was compelling in her own right, but the internal focus meant that the performers’ relationships to each other were often unclear, as were their relationships to the audio. The texture of sound and movement were both incredibly enjoyable as individual elements, but the animated relationship between the two that had characterized the night’s earlier works was lost in Rafters.

Once the music stopped and the applause began, I experienced what I had been longing for throughout the piece — a genuine responsiveness as the performers tried to figure out the mechanics of bowing to an audience that surrounded them.

That final moment of the night gave me my takeaway: truly noticing and attending to every element in a performance environment can heighten it all, whereas a passive engagement with one, be it sound or other bodies, risks diluting everything.

Tagged: Choreography, Contemporary, Performance, ON , Toronto