This article was originally published in The Current Society, The Dance Current‘s subscriber-only newsletter.

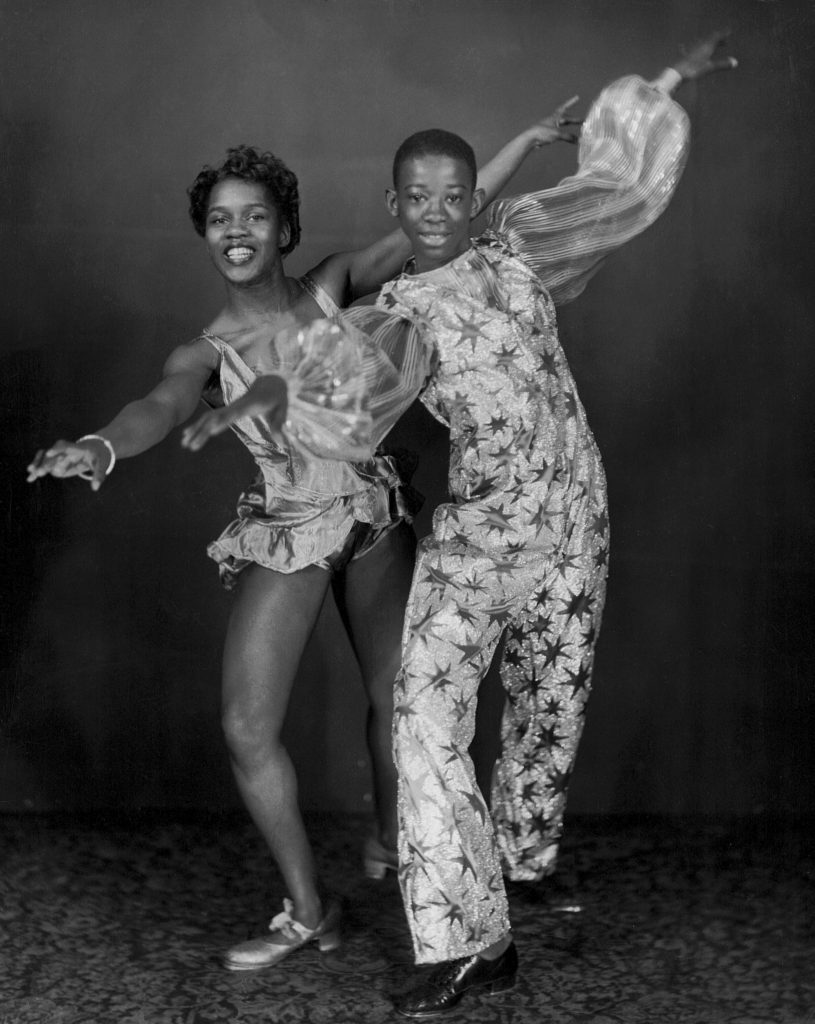

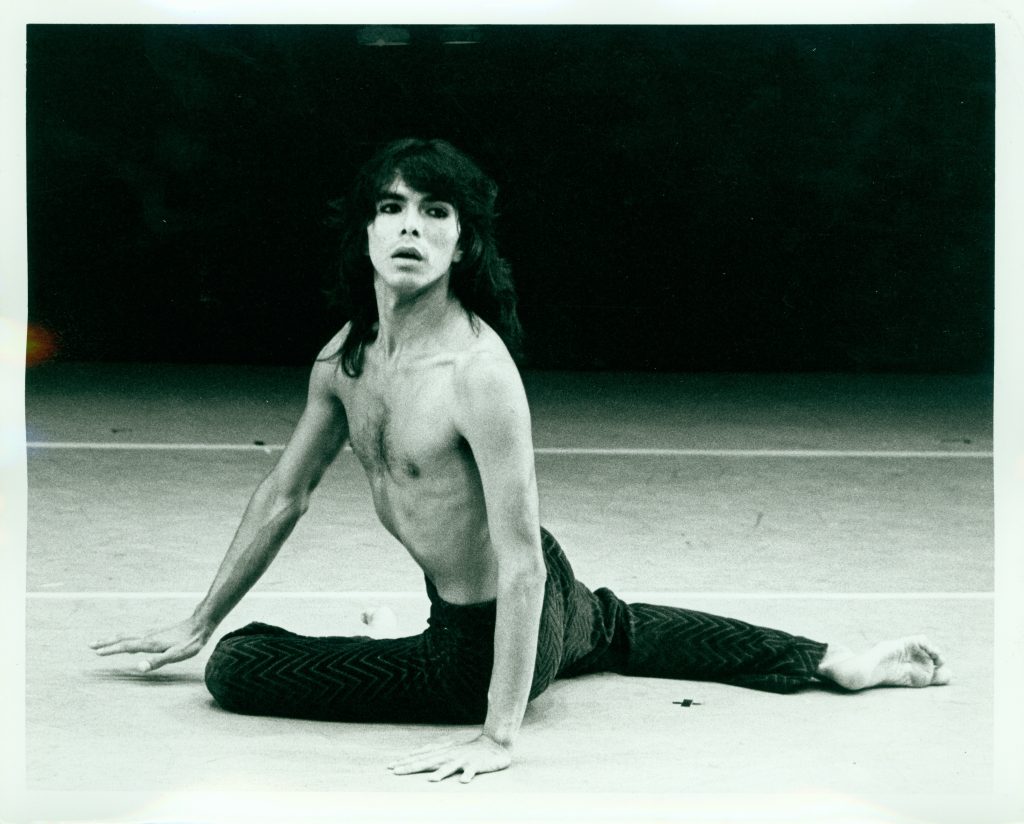

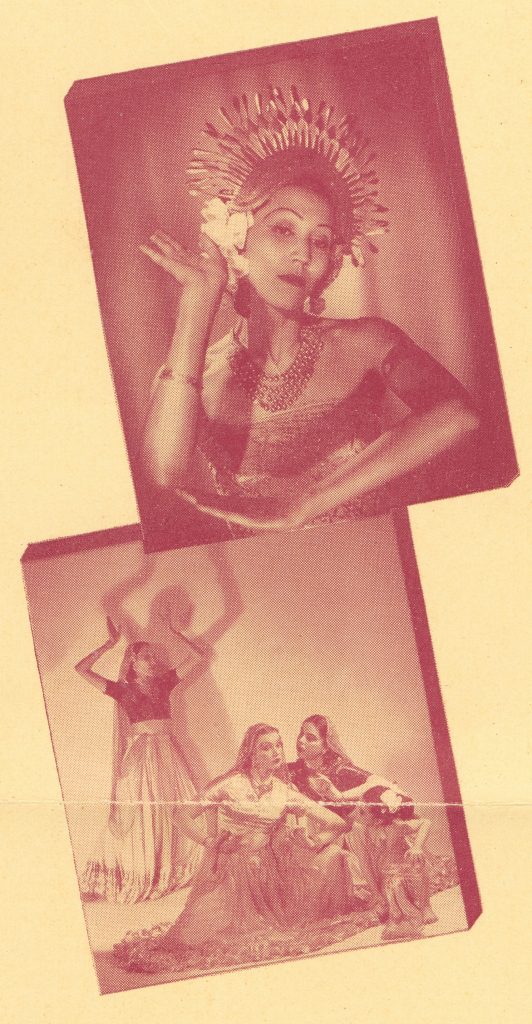

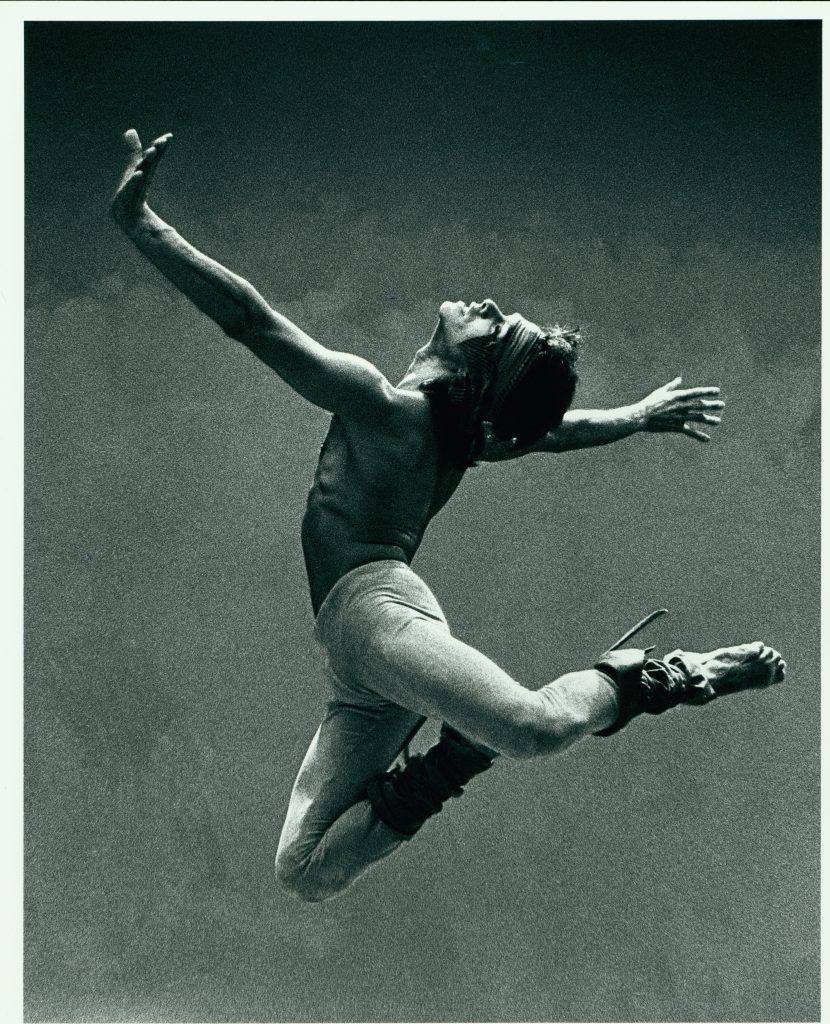

In the Fall 2022 print issue’s photo essay, Emily Pettet took a look back through history at some of Canada’s great dance educators. “Titans Through Time: Five educators, some more known than others, who helped shape the industry” spotlights Ethel Bruneau, Willy Blok Hanson, René Highway, Amy Sternberg and Saida Gerrard.

The Dance Current turned to Dance Collection Danse’s archives as well as the support of its executive and curatorial director, Amy Bowring.

Deputy Editor Anne Dion sat down with Bowring to look inside that process. “And,” she writes in the newsletter’s introduction, “it turns out that when you look inside dance archiving, you get a dazzling, prismatic view of all humanity. Each static shred of history still buzzes with the movement it once captured, and I will never be able to think of artistic history the same way.”

***

Anne Dion: So you’re the executive and curatorial director for Dance Collection Danse. Can you tell me a little bit about what that entails?

Amy Bowring: [Laughs] So there is the collections and programming side of it, and then there is the administrative side of it, right? So the [executive director] part is, you know, managing people and making sure things get done and then writing grant applications and working on budgets and board meetings, and all of that kind of stuff. And that, for me, is the necessity stuff. It’s the stuff I have to do.

The collections and programming is why I’m here. That’s what I’m in it for. The collections work is talking to people; people contact me and ask me if they can donate their archives, and we talk about what’s there and how much. I do a lot of work just guiding people in that process. Or people who want to maintain their own archives, they want to keep it themselves for a while, [they] will ask me for advice on the best way to go about doing that.

And then when we do get collections, we have to process them. So a lot of that starts with transferring everything into clean material: file folders, boxes. There’s a process called arrangement, where you try to keep things in the order in which they came, but sometimes you get stuff like, for example, someone’s passed away and their family donates their materials; they haven’t gone through them. Quite often they may not be a dance person themselves; they’ve sort of no idea what they’re looking at. And that’s when it might be just a big mess of things that they pulled together as they were getting ready to sell the house. [Laughing] I facetiously sometimes use the expression, ‘It looks like somebody barfed newspaper into a bag.’ Like, that’s literally how stuff turns up sometimes. And so that’s the more painstaking part, but it’s also really fun as you try to get to know a person’s life and career and put it into an order that makes sense for researchers.

One of the things that’s frustrating about being a dance historian is that so much of what we rely on to tell us what happened is based on newspapers and photographs, and of course, that’s all still, right?… Our primary artifact is intangible… [Our art] moves and disappears and only leaves traces behind.

Bowring

That’s another part, too, is working with researchers. We get lots of research requests from all kinds of different people: students, journalists, filmmakers, academics publishing papers, that kind of thing. So there’s a big process there in helping people find materials and guiding them in right directions and that kind of thing. Because sometimes people will call us and say, ‘What have you got on dance in Alberta?’ They may not have a very specific project. So I find that fun. It’s always great when you help a researcher find that eureka moment where they put things together and sort of build the story that they’re wanting to tell.

And then the programming side of it is also very fun because that’s with either curating exhibitions or working with guest curators, helping them with the research, helping them figure out how to put an exhibition together and how to tell the story.

Pre-pandemic, we did more things like scripts, film screenings and lectures and that kind of stuff.

AD: I love how, more and more, when I talk to people about their jobs, so many of them seem to boil down to storytelling. And I just think that’s beautiful.

AB: Yeah, it is. Isn’t it?

AD: So getting a little more specific, can you tell me a bit more about the process of researching for our recent photo essay, “Titans Through Time”?

AB: It was sort of a fun process. I love pulling out the really early history because I feel like that is the lesser known history. And people are always surprised by how far back Canadian dance history goes. Partly because we’ve been so dominated by the history of the United States and even the U.K. and Europe. So it’s great when we can pull out some of those early teachers. So [Grace] would mention a discipline and then I would think about it and think, ‘Oh, OK, there’s this person,’ and then we just sort of built it from there.

And then of course, finding photographs is always fun. I love our photo collection. I guess one of the things that’s frustrating about being a dance historian is that so much of what we rely on to tell us what happened is based on newspapers and photographs, and of course, that’s all still, right? It’s still images. It’s words, but they have a staticness to them. And especially with the really earlier histories, we have so little access to the actual movement, which really is our primary artifacts, right? Our primary artifact is intangible. It’s the movement itself, which [is] part of why preserving dance is such a challenge. I have art historian envy because their art form hangs on a wall and it stays still and they can stare at it for hours and make all kinds of analysis about it. And we don’t have that; ours moves and disappears and only leaves traces behind.

AD: That’s true, and a beautiful way of putting it, I think. But I wonder, what was your main takeaway after having done this research for “Titans Through Time”?

AB: Well, I guess it’s history I’ve known for a long time, which doesn’t mean other people necessarily know it. So I think my main takeaway is satisfaction in knowing that several generations of the readership will now know about these people where they may not have before.

AD: Did you come across anything specific that you were surprised by or that you didn’t know before? Did you run into any specific challenges with this project?

AB: Yeah, I did, actually. Because as we were looking, Grace was saying, ‘OK, what about early South Asian teachers?’ And I went back to Willy Blok Hanson, who’s really a complicated figure. And when I was reading [author Emily Pettet’s] writing, I realized that there were some things that I still had questions about. So I went in and started to dig through most of what we know about her because we don’t have her collection; we have the collection of one of her students named Garbut Roberts. And he did some really great notetaking and writing about that period. He has the sketches of a manuscript that he probably intended to publish at some point, but he passed away before he could. But he did a lot of writing about that period and learning South Asian dance forms from Willy Blok Hanson. [Hanson] grew up in Java, but she comes from a mixed Indigenous European background. She was there when the Japanese invaded; she was in an internment camp for a while. But she’s trained in Javanese and Balinese dance as well as bharatanatyam. She also spent time in Europe training in German expressionism, in modern dance.

The other fascinating thing about history is that our perspective as human beings is constantly changing, right? And how we look at history changes according to who’s looking at it, right?… Humans are complicated.

Bowring

The other fascinating thing about history is that our perspective as human beings is constantly changing, right? And how we look at history changes according to who’s looking at it, right? I mean, for a long time, you couldn’t find women in history; they just weren’t written about. And so as we go through this period of really looking at imperialism and colonization and how that impacted the world, and when we just look at that European dominance all over the globe, we see things quite differently. So when I was sort of re-looking at her history, because I had looked at the Garbut Roberts stuff when it came in, but that was years ago. And when I was re-looking at it with this different perspective, I just realized how complex her story was because of that mixed ancestry, because of what she was an enduring [during] what could have been the prime part of a dance career, with World War II going on and the Japanese invasion and so on. I just found it really interesting to look at her history and just see those perspectives from someone who had… I mean, the European side of her family was deeply rooted in colonialism. I think it was either a grandfather or great-grandfather, but he was in Indonesia for the harvesting of something, and I can’t remember what it was. That was typical of European imperialism, to go into these places and set up plantations and take stuff out. So that’s a part of her history. But then there were also marriages with, I think, a couple generations of Indigenous people in Indonesia in that area. And so, yeah, humans are complicated. It is a complex history. So I think that was probably the thing that surprised me most because I really delved more deeply than I had before when I first arranged that collection, and thinking about what these notes were telling me about her story.

AD: In general, why is archiving important for art and more specifically for dance?

AB: That’s probably one of my favourite questions. Because I get asked it a fair bit, it is a very good question. Because dance is so often seen as a frill, as just entertainment. But really, dance tells us a lot about our humanity and about our social histories, right? So if dance was just a frill, if it was not that important, then why did the Canadian government after Confederation feel like they had to ban Indigenous people from doing it? Obviously, it was an important enough part of their culture that the government said, ‘Wait a minute, if we want to assimilate and oppress these people, we need to take dance away from them, among other things, children, language, etc.’ So that’s a good clue as to actually how important dance is in the makeup of human beings.

Also, when we look at our dance history, we can see feminist history, we can see Queer history, we can see immigration history. It even factors into military history; dance was quite often used as a morale booster, as an aid for recruitment. It was used for patriotic purposes. We have examples in St. John’s, Newfoundland, and in Toronto, of performances specifically for patriotic purposes, to raise funds for the war effort.

We see when we look at some of these early teachers that are in [“Titans Through Time”], these are women who are working at a time period when you usually went from your father’s house to your husband’s house. So to have that financial independence of being a teacher and having your own income was huge. They weren’t suffragettes; they were actually living the suffragette movement. They had financial independence and they had a career. And that, of course, would have given them some kind of confidence, I’m sure, too, to be able to say, ‘This is my life, and this is how I want to live it.’ And that financial piece is huge, right? That’s one of the ways that women have been oppressed for so long – when you have to rely on a subsidy or an allowance from your father, and then an allowance from your husband, you are so limited in what you can do with your life and where you can go, so that’s huge.

Because dance is so often seen as a frill, as just entertainment. But really, dance tells us a lot about our humanity and about our social histories, right? So if dance was just a frill, if it was not that important, then why did the Canadian government after Confederation feel like they had to ban Indigenous people from doing it?

Bowring

And then Queer history: dance was one of the first places where it was safe to be Queer. Before homosexuality was decriminalized in the late 1960s, it was known that there were certain couples in The National Ballet of Canada, in other ballet companies, modern companies, and it was allowed, it was accepted. It was known that they were a couple even though what they were doing was actually illegal.

And then our immigration history, completely. Because as we see new art forms come into the country, it’s because people are bringing them with them, and that’s what humans do. They bring their food, their language, their dances, those aspects of their culture that are important. That comes with them when they cross oceans and go into new places.

And I’m convinced that there is a way deeper history. When you look at, for example, Chinese immigration, going back into the 19th century, we have practically nothing in the archives about the dances from that period. But they had to be there because that’s what humans do. And I’m convinced that if we could have better access to, say, community newspapers or language-based newspapers that were specific to a certain group of immigrants, we would know more about the dance history of those parts of the country because they weren’t covered by the mainstream media, which is where we get so much of our dance history. And of course, for the longest time, that was primarily ballet and then modern dance. And in fact, what’s really interesting, if you go right up till about the 1970s, most of the dance coverage in the mainstream media is in the women’s section of the newspapers. It’s considered ‘women’s work’ or ‘women’s activity.’ So it’s right there in with the bridge scores and the teas that people had, what certain socialites were doing – that’s where you’ll find the dance coverage, right through the 1960s.

AD: There are several very compelling cases in there about the importance of having specific resources for geographical and community-based spaces.

AB: Exactly. [Archiving is] important if we, as a dance community, want to say, ‘We were here, and this is what we did.’ Because our dances disappear unless they’re recorded on a media, which is not the dance itself. It is a recording of the dance. If we want to prove that we were here, this is what we have to do. We have to hang on to these materials and protect them so that they’re there for future generations to know the depth of the history here.

AD: I’ve been getting goosebumps for like five minutes! This is amazing. Are you or is DCD working on anything at the moment for 2023?

AB: Yes, actually. Our magazine is about to go out to subscribers and donors. And in it, I have a letter to say that one of the newer things that we’re doing is that we’ve commissioned Christopher House to curate an exhibition on the impact of HIV and AIDS on the dance community. Because it’s basically about 40 years ago that the first AIDS case came up in Canada. And so it’s foregrounded by a major research project, and then it will include a touring exhibition. So we’re at the start of what I estimate to be a three-year process.

We just opened Seika Boye’s exhibit, It’s About Time: Dancing Black in Canada. We opened that in Vancouver. And then there’ll be another iteration of it at the International Association of Blacks in Dance Conference, which dance Immersion is co-host for. And that’s in January at the Sheraton in Toronto.

This conversation has been edited for clarity.

Tagged: